“Breaking the Grass Ceiling” Challenges Women Experience in the Local Agriculture Sector

Session: Session currently unavailable

Date: 08 March 2022

Reference: NIA 180/17-22

Breaking the Grass Ceiling - Challenges Women Experience in the Local Agriculture Sector.pdf (1.29 mb)

Download a PDF version of this report (PDF, 85 pages, 1321KB)

Read a Summary Bill Report that highlights the key points of the full report

This report is the property of the Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

Neither the report nor its contents should be disclosed to any person unless such disclosure is authorised by the Committee.

Ordered by the Committee to be printed on 8 March 2022

Report Number: NIA 180/17-22

Contents

4. Terms of Reference and Methodology

6. The Local Agriculture Sector

7. Women in Local Agriculture: Data Analysis

8. Women in Agriculture: Policy Initiatives

Appendix 1: “Breaking the Grass Ceiling”: Survey Results

Appendix 2 – Education at Agricultural Colleges

1. Powers and Membership

- The Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of Strand One of the Belfast Agreement 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 48

- The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs and has a role in the initiation of legislation.

- The Committee has power to:

-

- consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- consider subordinate legislation and take the Committee Stage of primary legislation;

- call for persons and papers;

- initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

The Committee has nine members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, and a quorum of five. The membership of the Committee is:

Mr Declan McAleer MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Philip McGuigan MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Ms Clare Bailey MLA

Mrs Rosemary Barton MLA

Mr John Blair MLA

Mr Thomas Buchanan MLA

Mr Harry Harvey MLA

Mr William Irwin MLA

Mr Patsy McGlone MLA

2. Executive Summary

4. Historically women’s participation in the agricultural sector has been overlooked in what is overwhelmingly a “male-dominated” industry and women living and working in farming communities have been stereotyped based on traditional views about what their role should be.

5. In recent years there has been increasing awareness about the diversity and extent of women’s activities in agriculture and some governments are starting to adopt policies to support and encourage women to take on the leadership of farms and agri-businesses.

6. The local agricultural sector is predominated by men and women are significantly underrepresented in terms of farm ownership, primary farmer activities, participation in training support groups and on Boards of agri-food organisations.

7. Data from annual agricultural censuses shows that:

- Women comprise just 22% of the local agricultural workforce which is less than the UK-wide average

- Only 5% of registered principal farmers in NI are women

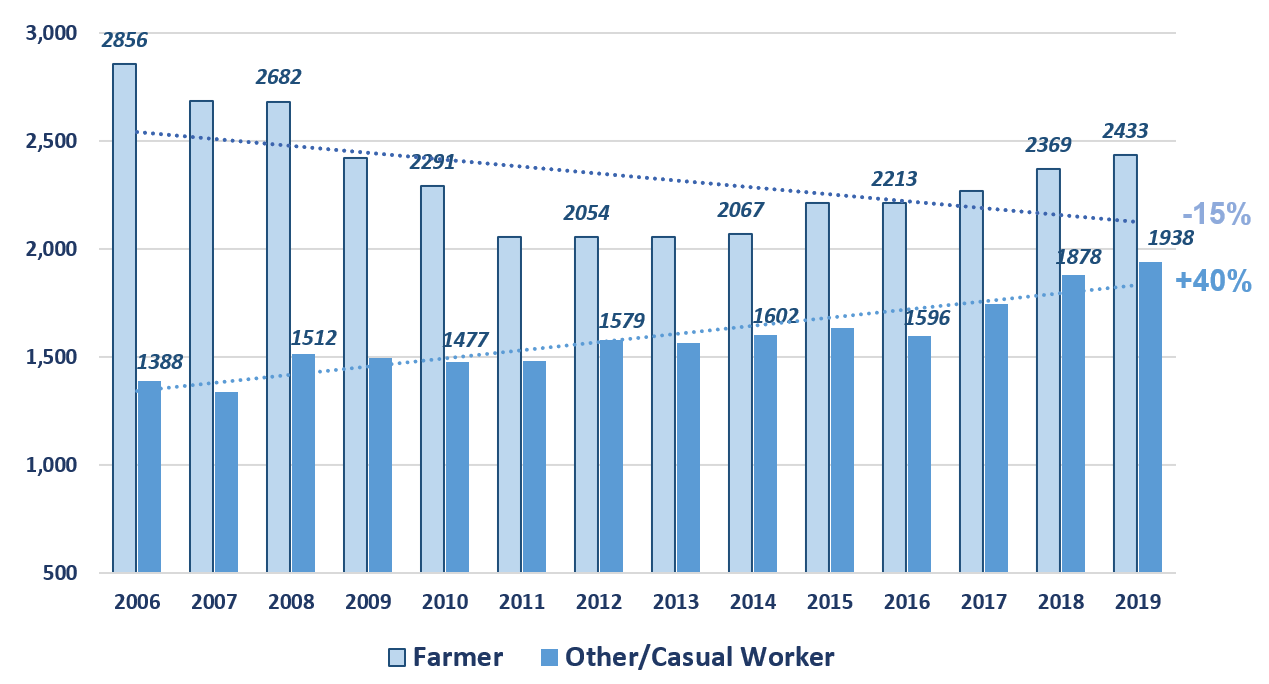

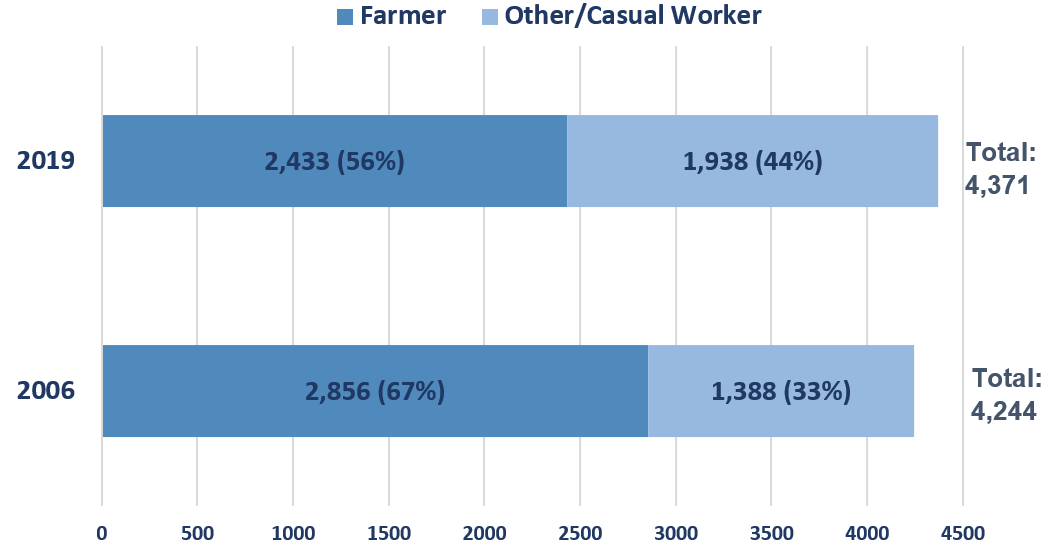

- Between 2006 and 2019 there was a significant change in the role of women working in agriculture with a 15% decline in the number of women farmers and 40% rise in women recorded as other/casual workers.

- Women account for just 4% of participants in farming Business Development Groups

8. Despite this, women play an extensive, diverse and crucial role on local farm-holdings which is very often not recognised. Over 95% of the local women who completed the Committee’s survey regularly undertake farming activities including livestock management, care of sick animals, equipment maintenance, as well as completion of paperwork. The vast majority spend in excess of 20 hours per week on farming duties in addition to having employment “off-the farm.”

9. The challenges women face are complex, multi-faceted and long-standing. Women experience a range of practical, social and cultural barriers which prevent them from taking on opportunities in terms of career development and progression in the sector.

10. Local women report a prevailing cultural attitude that it is not acceptable for them to be a farmer and that they are not treated with equal respect to male counterparts. Further, young women are often discouraged from pursuing jobs in agriculture by their family as it is deemed to be an unviable career path for a woman.

11. Traditional inheritance practices of granting farm ownership to son(s) in farming families is a significant barrier and severely limits women’s opportunities for farm ownership.

12. Preconceived notions and expectations of women to care for children and elderly relatives is a further challenge as this encumbers on opportunities and time available to engage more extensively in farm work.

13. Generally, the lack of women role-models in the sector inhibits the chance to showcase the capabilities of local women in agriculture and perpetuates the image of a male-dominated industry.

14. Practical challenges in terms of access to finance, training and mentor-support are further barriers to women progressing their skills and opportunities to manage farming businesses.

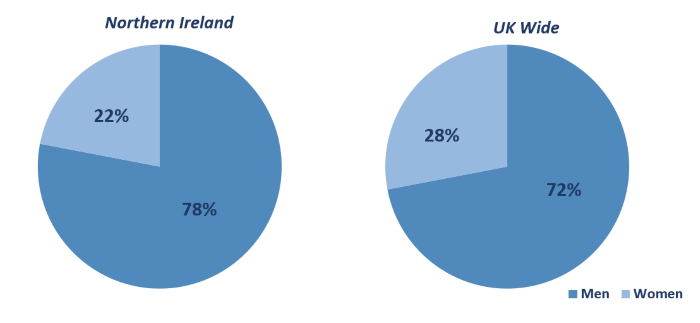

15. The overwhelming majority, over 95%, of local women who engaged with the Committee’s review consider that more needs to be done to support women in the sector and less than half consider that farming provides equal opportunities for men and women.

16. While many of the challenges experienced by women in agriculture are interwoven with cultural practices and traditions, and will therefore take many years to overcome, there is a range of practical and policy measures, reflective of those introduced in other jurisdictions, which could be taken forward to promote, encourage and support women in the sector.

3. Introduction

17. This report outlines the findings of the Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (AERA) following its review into the challenges experienced by local women in the farming and agricultural sector.

18. The review was undertaken in order to identify the barriers women face in terms of taking on leadership roles in agri-business and to inform recommendations for future policy provision in this area.

19. It includes:

- The Terms of Reference and methodology followed to collate evidence

- Traditional and contemporary views of women's role in agriculture

- An overview of the local farming industry including strategic policy drivers

- An analysis of available data in terms of the agricultural workforce

- A comparison of policy approaches in neighbouring jurisdictions

- Information pertaining to student enrolment at agricultural colleges locally and further afield

- The results of a survey carried out with members of the public to gather their views

- The key issues arising from engagement with stakeholders

- Recommendations for future policy provision to encourage and support women to have a more prominent and active role in the local agricultural sector

4. Terms of Reference and Methodology

20. The Committee agreed in November 2021 to progress a targeted and focussed review of policy provision in respect of the challenges facing local women in the agriculture sector, with a view to completion before the end of the current electoral mandate (March 2022).

21. This subject was selected for a number of reasons, including, but not limited to, the fact that:

- Women’s role in agriculture has received little policy attention and focus from public bodies

- It is widely accepted that, historically, women’s interests in the sphere have been underrepresented

- Other jurisdictions have enacted specific policies to promote gender equality and women’s participation in agriculture

- The local farming industry is on the cusp of a period of significant flux driven by policy, economic and social changes

22. The Terms of Reference for the review were as follows:

- To capture the current experiences of local women in agriculture of different ages and their role

- To identify the challenges and barriers that women face in taking on the ownership and running of farms and leadership roles in agri-business

- To benchmark policy initiatives across different jurisdictions in this area

- To make recommendations for future policy provision

23. The Committee engaged in a range of activities in order to gather evidence to support its considerations.

24. The primary method of data collection was through a survey that was made available online between 3 December 2021 and 14 January 2022 which sought to capture the current activities, experiences and views of local women.

25. The Committee undertook a literature review to inform survey design and consulted with key stakeholders – the Ulster Farmers’ Union and Northern Ireland Rural Women’s Network- before launch for their views and considerations.

26. Additionally, data relating to the composition of the local agriculture workforce was analysed in order to provide a comparative assessment about the number of women working in the sector and how this has changed in recent years.

27. The Committee also engaged with the Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) to understand what current, and potential future, policies are in place to support women within the sphere. This was augmented by contacting relevant Departments in England, Scotland, Wales and the Republic of Ireland to assess their policy provision.

28. In February 2022 the Committee facilitated an event with stakeholder groups representing local women engaged in agriculture to hear from them, first hand, what the issues are, their views for the future of the industry and how women can be better supported to engage in agri-business as a viable career option.

5. Women in Agriculture

The Tradition

29. For centuries farming has been perceived as a “man’s job” due to preconceptions about the need for certain physical abilities to carry out activities like managing animals and operating machinery and equipment.

30. The tradition within farming families of passing farm ownership to a son(s), or other male relative, has compounded this and precipitated a “male-dominated” industry with men having primacy in terms of leadership roles on farms, in other agri-businesses and in farming-related organisations.

31. The stereotypical view of women living and working in the agricultural sphere has often been characterised as follows:

A Farmer’s Wife whosupports the farm family by looking after children and domestic duties, while supporting her husband in fieldwork and other tasks as needed

A Farmer’s Mother: matriarch who maintains influence over her family and provides mentorship and advice to the younger generation

A Farmer’s Daughter: raised on a farm and taught from a young age to help with practical tasks and is often encouraged to marry into a farming family

The Modern View

32. The traditional stereotypes of women in agriculture belie the diversity and importance of women’s activity in the sector. It is estimated that women account for more than 50% of the world’s food production and comprise the vast majority of farm workers in Africa and Asia.

33. A number of studies have shown that women, when given the same access to equipment, training and finance are equally productive as men engaged in the same type of farming activity.

34. Further, women are more likely to diversify farm operations and employ new methods to generate income. For example, women have been found to have a greater propensity for inter-cropping and introducing initiatives such as agri-tourism on farm holdings: women farmers are therefore increasingly being recognised as drivers and catalysts for change.

35. Women farm managers tend to prioritise different business goals than men and are more likely to introduce schemes to enhance environmental and eco-system health and support long-term sustainability.

36. It is also widely acknowledged that farming women are often primarily responsible for domestic duties including family care, cooking and cleaning, as well as financial management, bookkeeping and paperwork related to the farm business. This is in addition to practical farm tasks.

37. Women also play a vital role in supporting farm operations through off-farm employment. Many women in farming families have jobs in other sectors and their salary is often used to meet farm running costs or secure loan capital for the business – a 2019 survey of Australian farm workers found that 75% of women supplemented their farm’s expenses through off-farm employment.

38. Despite the extensive and varied role that women play, their contribution, status and value to the agriculture sector is often overlooked, marginalised or not given equal merit– they are often described as “invisible farmers.”

A Changing Situation?

39. There is emerging evidence which suggests that there may be a shift underway in some countries in terms of women taking on a more active role within the farming industry.

40. For example, it is estimated that there are approximately 23,000 women farmers operating in England which is significantly higher than a decade ago: the number of women farmers increased by 7% from 2007 to 2018. Further, a 2017 study in the United States showed a 27% increase in the number of farms registered to women owners since 2012.

41. While these data suggest an increase in the active participation of women in agriculture management, they must be considered carefully as many countries have adjusted methodologies for collecting farm census information to try and take account of the varied role of women in the workforce.

42. Therefore, while it is likely that more women have taken on farm leadership roles in recent years, the vast majority of women experience significant challenges, in what is still an overwhelmingly male dominated industry.

The Barriers

43. It is recognised that women experience a range of practical, social and cultural barriers that limit their opportunities to progress within agri-business and pursue viable career paths in the sector, including:

- Succession Practices –sons, and other male relatives are, in the vast majority of cases, prioritised over daughters in terms of farm/land ownership

- Access to Capital – women often report difficulties associated with trying to secure loans to support their businesses as lenders may be less willing to grant capital to a woman farmer

- Training and Education – for years formal agricultural training and education has been geared towards young men and the provision of training has not taken account of the needs of women in the sector

- Caring Responsibilities – generally, women undertake more caring responsibilities than men, both in terms of childcare provision and for elderly relatives. This can discourage women from pursuing a career in the agricultural sphere given the substantive time demands required to run a farm, with activities often needing to be done in the early morning and in the evening

- Social Stigma – women who have, or those who have expressed an interest in, managing a farm business often cite a lack of support from friends and family with it being perceived as culturally unacceptable

6. The Local Agriculture Sector

44. The agri-food industry is key to the Northern Ireland (NI) economy and local farmers are renowned for the development of high-quality meat, dairy and crop produce.

45. Together with food and drinks processing, the agri-food sector generated approximately £5.4 billion in economy activity in 2019 and it supports employment for thousands of local people, as well as jobs in hospitality, retail and other industries.

46. The vast majority, around 80%, of local farmland is used to rear livestock (predominantly cattle and sheep) for the generation of meat and dairy products. The total calorific output from the local farming industry is sufficient to sustain around 10 million people and NI exports a significant proportion of its agri-produce to neighbouring jurisdictions in Great Britain and Ireland, as well as further afield.

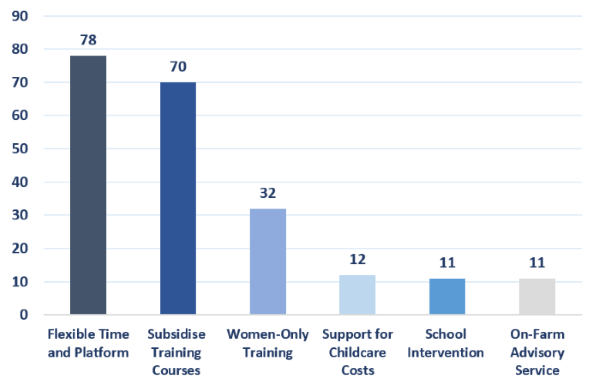

47. There are approximately 25,000 registered local farm holdings and the vast majority are designated as “Very Small.” The aggregated income per farm business for 2021-22 is projected to be in the region of £33,000. However, profitability margins are low - in 2020 just under a fifth of local farms made an operating loss – and farmers are reliant on the system of direct payments which comprised 96% of net farm business income in 2020.

48. The agricultural sector is facing a profound period of change due to several legal and policy developments that will directly impact local farmers including:

- Brexit-related Trade: Following its exit from the European Union (EU) on 1 January 2021, the UK signed Free Trade Agreements with a number of countries including Australia and New Zealand which are mass producers of agri-food. This raises the prospect of food and dairy items produced at very low cost entering the UK market, posing a direct economic challenge to local farmers.

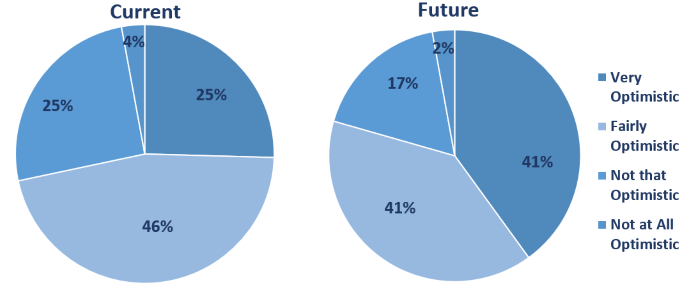

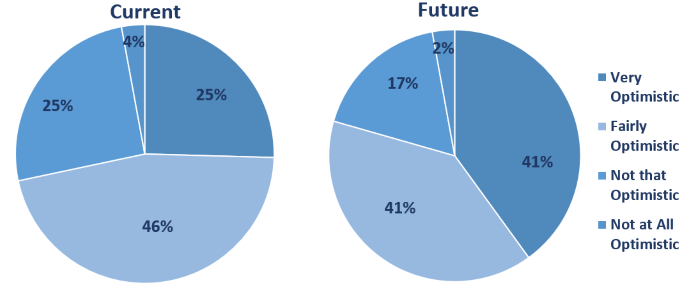

- New Direct Payment System: As highlighted above direct payments from government are essential to maintaining local farm operations. Prior to Brexit, the system of direct payments was facilitated under the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and for the past two decades allocation has been based on the total area of land managed.

However, similar to proposed changes in England and Ireland, the area-based direct payment system in NI will change over the next 5-10 years to incentivise farmers to engage in nature-friendly and environmental practices.

This will represent a step change in how direct payments are made and will necessitate a significant shift at farm-level.

- Climate Change Legislation: the local agriculture sector accounts for around 27% of the greenhouse gases emitted by NI industry. This is due to the high number of ruminant livestock (cattle, pigs, sheep etc.) on local farms which contribute to methane emissions through their digestive processes.

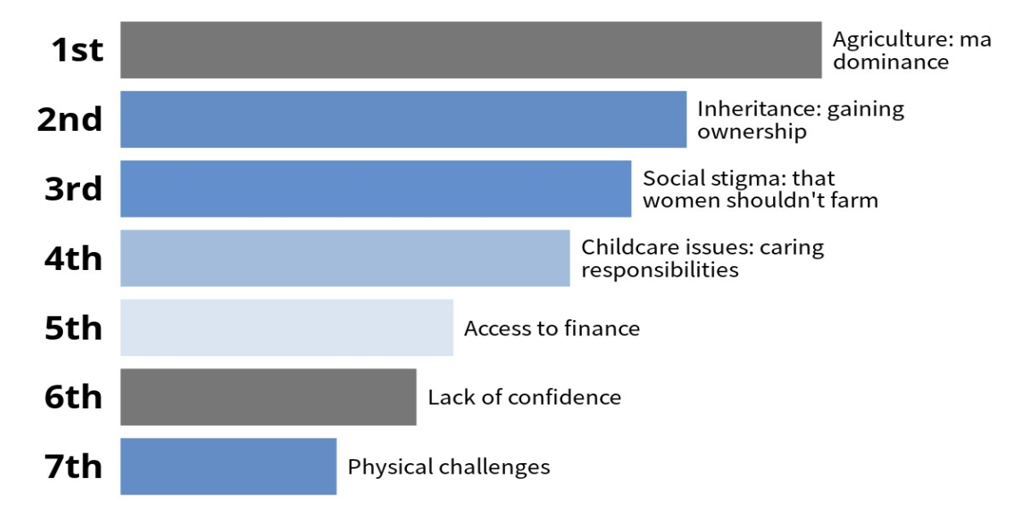

As part of the global pledge to reduce global warming, NI industries will be obligated to reduce their emissions via legislation that will come into effect in 2022.

While the precise impact of this is as yet unknown, the agri-food sector will invariably be compelled to change its operating model to make a fair contribution to emissions reduction.

7. Women in Local Agriculture: Data Analysis

49. DAERA and responsible Departments in other jurisdictions regularly collect data on the composition, output and scale of the agricultural sector in their respective localities.

50. Each June DAERA conducts a survey to gather information about the size, number, activity and workforce on local farms. In order to help inform the Committee’s considerations an analysis of these annual statistics was undertaken covering the period 2006 to 2019. Data relating to the 2020 census was excluded due to methodological changes introduced in this year which led to a step change in the number of registered farms compared to previous years.

51. The key points are summarised below.

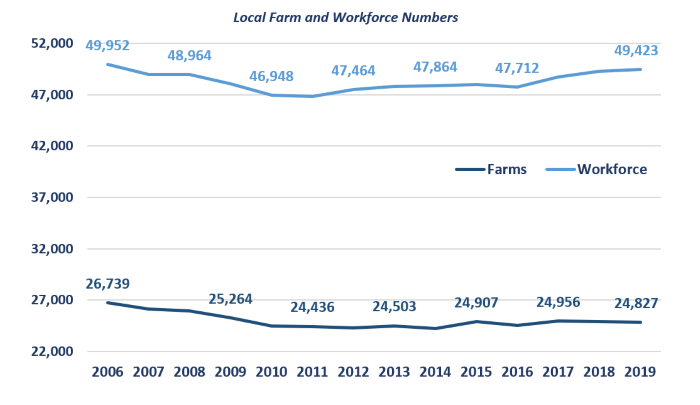

Number of Registered Farms and Workforce

52. The below graph illustrates the registered local farm holdings and total agriculture workforce numbers each year. It demonstrates that while there was a 7% decline in the number of farms between 2006 and 2019, the overall workforce figure remained relatively stable, with approximately 49,000 people working in the sector, and a slight increase in overall workers since the early 2010s.

53. This trend is reflective of dynamics seen across the UK and EU with increasing consolidation of holdings due to potential heirs in farm families less inclined to pursue agriculture as a career, in favour of other forms of employment.

Workforce Sex Split

54. The sex breakdown of workers in the local sector has remained consistent over the past 15 years with men comprising approx. 78% of the workforce and women 22%.

55. While not surprising, there is evidence to suggest that there are fewer women working in the local agricultural sector compared to other jurisdictions

56. The Committee requested a report from the Office for National Statistics on the gender breakdown of registered farm workers in all regions of the UK from its available information sources.

57. This report showed a very similar sex split in NI as the DAERA census (78%/22%) but that across the UK women accounted for 28% of agricultural workers: this suggests that there may be a higher number of men in the local farming workforce, compared to other regions.

ONS Data Request: Sex Split in Agriculture Workers 2020

Principal Farmer

58. The DAERA census captures the “principal farmer” on each holding: the main decision-maker or owner of the land/livestock. Unsurprisingly the vast majority of principal farmers are men (around 95%) and there has actually been a decrease in both the number and proportion of local women principal farmers since 2006:

Percentage of men and women “Principal Farmers” on each holding since 2006

|

Year |

Men |

Women |

|

2006 |

93.75% |

6.25% |

|

2009 |

94.41% |

5.59% |

|

2012 |

94.68% |

5.32% |

|

2015 |

94.56% |

5.44% |

|

2019 |

94.70% |

5.30% |

59. Given disparities in how registered owners are defined and recorded it is difficult to facilitate a meaningful comparison between jurisdictions but there is information which suggests that there are fewer women recorded as the principal operator/owner of farms locally, compared to other areas.

60. Data from 2016 indicates that men comprised 84% and 88% of farm holders in England and ROI respectively and that across the EU 22% of registered farm owners were women (on average).

Changing Role of Women Workers

61. The data suggests that the role of women working in agriculture has changed since 2006. The graph below shows that the number of local women farmers has fallen by around 15% and conversely the number of women recorded as other/casual workers on farms has increased by around 40%

62. Relatedly, there was a sharper decrease in the number of women principals over this timeframe compared to men: a 21% and 6% decline respectively.

63. This suggests a shift in the working dynamics of local farm women who are less likely to have primary, management roles than they were 15 years ago, and are increasingly engaged in work that is more supportive in nature.

64. This is further exemplified in the below graph which shows that while the overall number of women engaged in farm work in 2019 was broadly comparable to 2006, the composition in terms of their role has changed significantly:

Comparison with General NI Workforce

65. In relative terms there is a much greater sex imbalance between workers in the agriculture sector compared to the wider NI economy as shown in the below table:

|

Sex |

Agriculture Workforce |

NI Economy |

|

Men |

78% |

52% |

|

Women |

22% |

48% |

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

66. There is also a greater propensity for women in agriculture to be engaged in part-time/casual working than their counterparts in other sectors: the proportion of women working in agriculture on a full-time basis in 2019 was only 30%, compared to 62% in the general workforce.

Board Representation

67. The Committee looked at the composition of Executives at 17 local agri-food organisations and businesses in terms of the sex of senior managers at Board level – this encompassed major players in the local sector including agriculture organisation, education and private agri-food production enterprises

68. As of December 2021, out of the 111 senior Board representatives at these organisations only 16 were women: about 14%.

Uptake of Support Schemes

69. DAERA facilitates a range of financial and training support schemes for local farmers.

70. Unfortunately, the sex of applicants to Area-Based Schemes is not captured so the Committee was unable to analyse this information. However, DAERA did provide information pertaining to the 2021 applications for Tier 1 Tranche 3 of the Farm Business Improvement Scheme: 148 applicants (5%) were women which correlates to the proportion of registered women principal farmers.

71. DAERA also manages the Business Development Groups (BDGs) Scheme which provides funding for farmers to engage in group training and knowledge-sharing with the aim of improving the technical efficiency and profitability of farm businesses.

72. As of December 2021, there were 3,243 members participating in 162 BDGs throughout NI:

- 3,119 (96.2%) were men which comprises approx. 11% of male farmers recorded in 2019 census

- 124 (3.8%) were women, constituting approx. 5% of women farmers

73. This suggests that women farmers may be less inclined to engage in BDGs than men, which could potentially limit their opportunities for skills and business development.

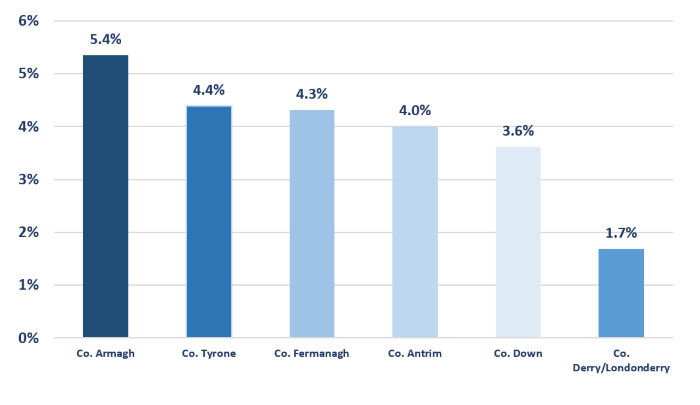

74. Further, there is regional variation with proportionally fewer women participating in BDGs in Counties Derry/Londonderry and Down than in other areas:

Percentage of Women BDG Members

Women in the Local Agriculture Workforce: Summary

- There was a 7% decline in the number of locally registered farms between 2006 and 2019, but the total workforce figures remained fairly stable over this period

- Women comprise just 22% of the local agriculture workforce and this appears to be lower than in neighbouring jurisdictions

- There was a fall in the number of women recorded as principal farmers between 2006 and 2019 and men make up 95% of registered principals: this is a lower proportion of women farm ownership seen in England and ROI

- There was a shift in the role of women within the local workforce between 2006 and 2019 away from primary farming roles towards other/casual working activities

- There is an imbalance in the sex composition of the agriculture workforce compared to the wider NI economy, and women working in agriculture are much more likely to have part-time/casual roles

- Membership numbers suggest that women farmers are less inclined to engage in the work of BDGs than men and there is regional variation in terms of the extent of women’s participation

- Women are significantly under represented at senior decision-making level in local agri-food organisations

8. Women in Agriculture: Policy Initiatives

75. Jurisdictions across the UK and Ireland have, to varying degrees, introduced, or are actively developing, policies to address some of the challenges facing women in agriculture and to support them to have more prominence in the sector.

Scotland

76. The Scottish administration has been the most ambitious of the UK authorities in terms of engaging in this policy area and Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister, commissioned a “Women in Agriculture Taskforce” in 2017 to scope the specific issues.

77. The Taskforce reported on its findings in November 2019 and made a series of recommendations which were endorsed by the Scottish government to be taken forward with £300,000 of annual funding pledged until 2024-25. This has recently been increased to £400,000 per annum with the potential for additional resource depending on outcomes of the main workstreams, which include:

- Diversity and unconscious bias training for key agricultural organisations: seven large agri-businesses took part in Board-level diversity training between November 2020 and January 2021. The majority of participants reported positive feedback and have developed action plans to increase diversity

- Introduction of a “Women in Agriculture Development Programme” to facilitate training and mentoring to build women’s confidence, business and leadership skills.

In 2020-21 this encompassed delivery of a pilot training scheme “Be Your Best Self” to help women share experiences, learn from each other and improve decision-making. 200 training places have been funded for 2021 and 2022, with an additional pilot business training scheme to be taken forward

- Increasing training opportunities for women including women-only programmes.

The Scottish government provided £215,000 in 2021 for the “Women in Agriculture Practical Training Fund” which enables applicants to claim up to £500 per course on topics such as business skills, environmental sustainability, health and safety and machinery/equipment operation

- Scoping provision of childcare services in rural areas and how this can be improved

- Succession planning campaigns to focus on the need for early future-proofing and consideration of all children as potential successors

- Encouraging inclusive language in schemes designed to support new entrants and promotion of opportunities for women where possible

- Specific Health and Safety training geared towards women

Wales

78. The Welsh government has supported initiatives for women in agriculture via its “Farming Connect Programme” which was part funded by the EU until 2020 with a focus on developing women’s skills and expertise via:

- Annual Women in Agriculture Conferences

- Discussion and Action Learning Groups – women-only forums held physically or virtually in different regions to enable women to discuss technical issues, farm diversification and social media engagement

79. The Welsh government has provided extended funding for the Programme until March 2023 and is committed to long-term resourcing of further initiatives in this area.

England

80. While the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) currently does not have any active policies in place, it has undertaken research in this field and identified priorities for future policy development to support women in agriculture including:

- Targeting communication to ensure women are aware of the schemes, support and funding that they may be entitled to

- Giving specific consideration to the Health and Safety needs of women farmers such as provision of additional safety equipment and better education

- Ensuring that schemes for land access and entry are fair and inclusive

- Encouraging opportunities for earlier family discussions on succession planning

Ireland

81. In advance of the roll-out of the EU’s CAP for 2023 to 2027, the Irish government has pledged a number of measures to its existing support schemes in order to enhance accessibility for women and promote gender equality.

82. The grant aid limit for the Targeted Agricultural Modernisation Scheme (TAMS), which provides financial assistance for the upgrade of farm machinery and equipment, has been increased from 40% to 60% for women applicants aged between 41-55. This is designed to encourage women farmers to modernise their capital assets.

83. A commitment has been made to develop women-only forums under the “Knowledge Transfer Scheme” which supports peer-peer learning for farmers, given that women comprised just 16% of participants in such groups between 2018 and 2022. The rationale is to facilitate environments in which women feel confident to raise issues and to mitigate any social stigma that may arise in a male-dominated meeting.

84. The Irish government has called for proposals to examine women’s participation in agriculture via the European Innovation Partnerships (EIP) initiative.

Northern Ireland

85. The Committee sought information from DAERA about the current local policies which aim to enhance support for women working in the agricultural sphere:

- 2021/22 Changes to Further Education Support: A grant of up to £400 per year is available to part-time students enrolled at the College of Agriculture, Food and Rural Enterprise (CAFRE) to help with the cost of resources and travel. Successful applicants are able to access the CAFRE Childcare Allowance and the Hardship Fund Childcare Allowance to assist with the completion of studies

- Widening Access & Participation Plan (WAPP): CAFRE is developing a WAPP for implementation 2022 which will set out its strategy to address under-representation in its courses, including specific actions and targets for improving gender under-representation.

A range of initiatives are being considered including financial bursaries, a potential move to extended online course delivery online and increasing the number of student support officers available at the College.

- Future Agricultural Policy proposals – Generational Renewal Workstream: This is being progressed to explore a comprehensive approach to issues associated with succession planning and inheritance within farming families, as well as developing the skills of the identified successor. This will provide “an opportunity to encourage more females into the industry.”

86. DAERA’s consultation on Future Agricultural Policy Proposals which was published on 16 December 2021 notes that “DAERA is cognisant of the need to encourage females in farming and to eliminating any perceived barriers to accessing the industry as a viable career path.”

Policy Initiatives Summary

87. There is wide variation between jurisdictions in terms of the policy framework, and allocation of resources, that have been enacted to address challenges faced by women in agriculture, with Scotland and Ireland implementing measures to provide practical, financial and training support for women farmers.

88. The disparity in approach is reflected in the legal text underpinning the forthcoming 2023-27 CAP which obligates EU states to “promote employment, growth, gender equality, including the participation of women in farming” and outlines that:

“Equality between women and men is a core principle….and gender mainstreaming is an important tool in the integration of that principle into to the CAP. There should therefore be a particular focus on promoting the participation of women in the socio-economic development of rural areas, with special attention to farming.... Member States should be required to assess the situation of women in farming and address challenges in their strategic plans. Gender equality should be an integral part of the preparation, implementation and evaluation of CAP interventions.”

89. Conversely the terms “woman”, “women”, “gender”, “female” and “equality” do not appear in either of DEFRA’s The Path to Sustainable Farming: An Agricultural Transition Plan 2021-24 or Farming for the Future 2020 policies, which set the future strategic framework for farming in England.

90. Nevertheless, to varying degrees, governments are beginning to recognise the important role that women play in the agricultural sphere and how they can help the industry modernise and meet new challenges in the years ahead, and are engaging in policies to enable women to do this.

9. Survey Results

91. In order to help inform its views the AERA Committee made a survey available online from 3 December 2021 to 14 January 2022 to seek the views of local women about the barriers and challenges which they experience.

92. The full results are outlined at Appendix 1 and the key points are highlighted below.

Respondent Demographics

93. The salient data relating to respondent numbers, demography, farm type and geography were as follows:

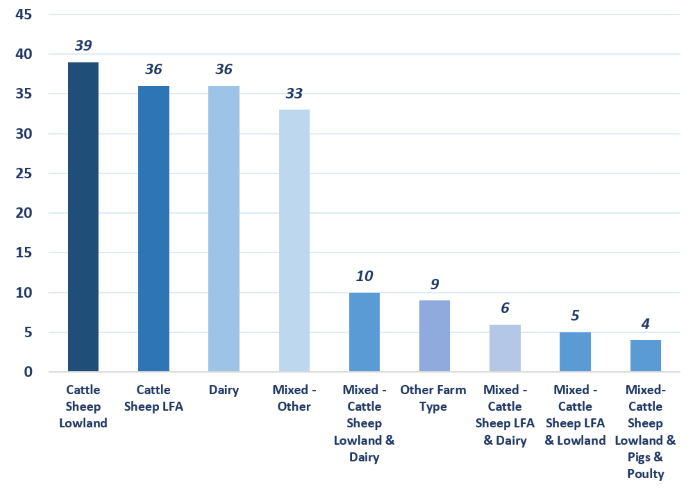

- There were 178 responses from women within the target demographic, i.e. individuals currently living/working on a farm and/or who were raised on a farm

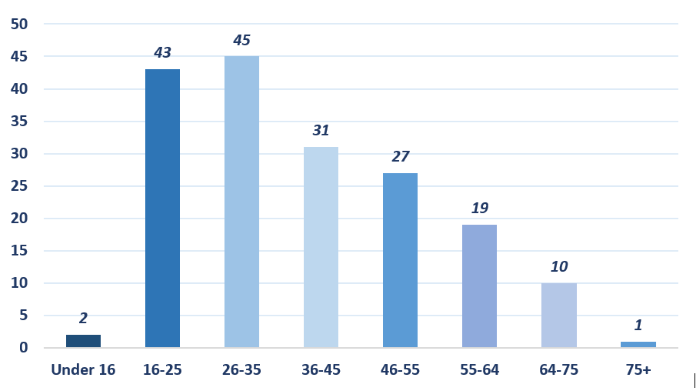

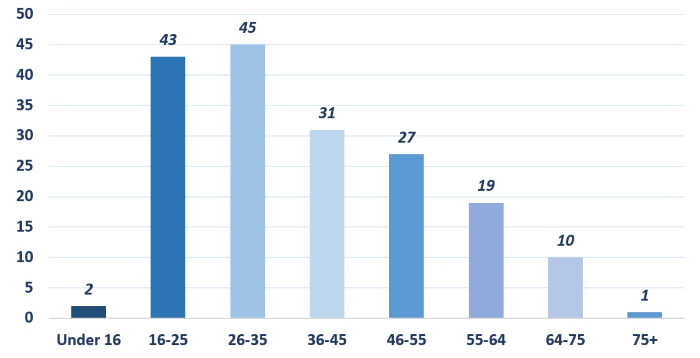

- The majority of respondents, 67%, were aged 45 or younger and the age band spread is shown in the below graph:

Respondent Age Range

- Just over half of returnees have completed formal education or training in relation to farm management

- 47% actively participate in, or are associated with, local farming organisations and clubs

- The table below shows the breakdown of the type of farm returnees work/live on:

|

Type of Farm |

Number |

% |

|

Cattle Sheep Lowland |

39 |

22% |

|

Cattle Sheep LFA |

36 |

20% |

|

Dairy |

36 |

20% |

|

Other Farm Type |

34 |

19% |

|

Mixed – Other |

33 |

19% |

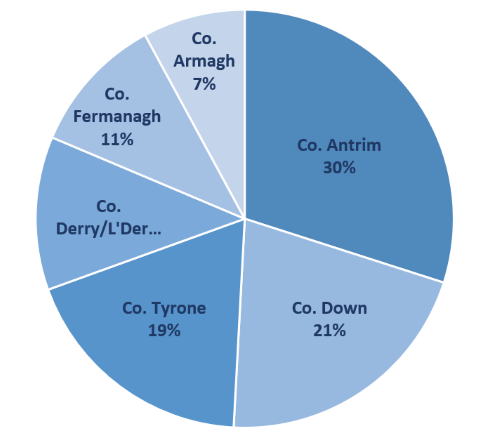

- Responses were received from women living on farms in all counties and 70% reside in Counties Antrim, Down and Tyrone

Farm Ownership and Decision-Making

94. Respondents were asked who the primary decision maker is on their farm and the extent of influence they have regarding decisions:

- 83% outlined that a man owns the farm on which they work or live. While not unexpected, this figure is lower than the DAERA agricultural census data that approximately 95% of principal farmers in NI are men.

This suggests that the respondents to the survey disproportionately represent farms with women owners and therefore are not entirely reflective of the total agricultural workforce, or there could potentially be more farms owned/controlled by women than is currently captured through the census data collation methodology.

- 75% of returnees explained that a man makes most of the decisions on the farm. The disparity relative to the fact that 83% of returnees live/work on a farm owned by men suggests that ownership does not directly correlate to daily decision-making and that women may have a greater influence over farm business decisions despite the fact that they are not the named, legal owner

- The vast majority of respondents consider that they have some say over on-farm decisions with 15% describing themselves as the “Final Decision Maker”. Conversely 23% of returnees reported that they have “Little to No Say”

- 70% believe that if they had an idea to diversify farm operations or change how things are done that this would be supported. However, respondents commented that ideas for change put forward by men living/working on a farm are more readily supported than those suggested by women:

“The farm is mainly run by the men of the family, but being a girl, I make sure I’m heard and if something isn’t working, I will make sure it’s sorted”

“Sometimes yes, it is heard and understood, although if it came from another man it would [be] listened to better.”

On-Farm Role

95. Returnees were asked about the extent of their involvement on their farms and the type of activities which they are responsible for:

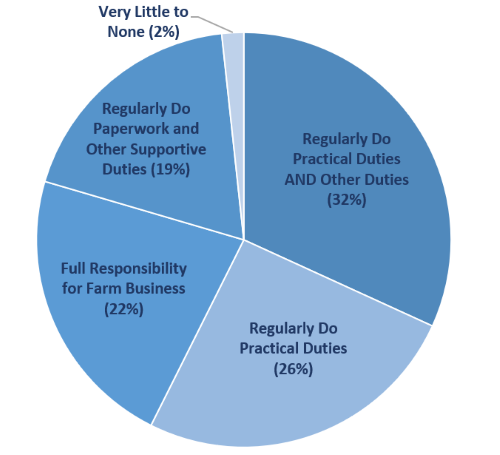

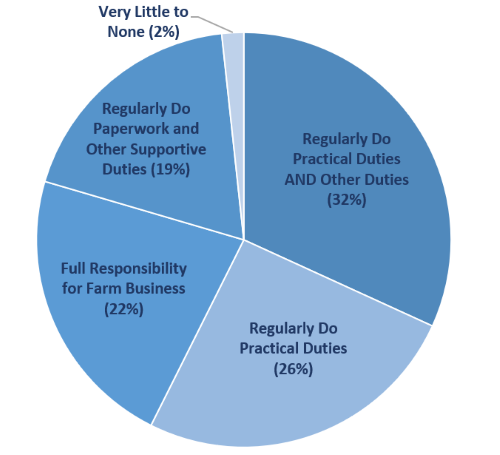

- The overwhelming majority of returnees, 98%, regularly participate in farm activities and just under a third regularly complete both practical “hands-on” tasks in addition to “supportive” jobs such as completion of paperwork and form-filling:

On-Farm Role

- Women undertake a diverse range of activities on local farm holdings as illustrated in the below comments:

“I help at lambing time, fencing, dosing sheep, cleaning out the sheds as well as farm paperwork”

“Daily milking, rearing calves, feeding livestock, bookwork, lambing sheep and care of lambs, general livestock care i.e., dosing weighing etc, and other general farm duties as required”

“I am the back bone of the farm I do every job on the farm on a day to day…My jobs range from calving cows, lambing ewes, slurry spreading, farmyard manure spreading, rolling, mowing, tedding & baling all the silage/haylage & hay for the livestock to feed them over the winter months, then drawing and stacking off round bales, dosing & all the general day to day things to do with all the livestock.”

“I complete milking of the cows twice daily, as well as making diet feeds for the cows, I also scrape and bed cubicles. In the summer time I put in the grass which includes mowing, raking and lifting or baling and wrapping. I also help with the rearing of calves and administer medicine if cattle are sick. As well as outside jobs I complete most the farm paper work as well.”

- A significant proportion, 25%, of women who responded to the survey have primary responsibility for administration activities on their farms and whilst a significant number take the lead on certain aspects of livestock management, these tend to be less physically intensive tasks compared to manoeuvring, catching and controlling animals

- The table below shows the amount of time, on average, respondents to the survey spend per week on farm work, with just under a fifth working more than “full-time” hours and the majority contributing over 20 hours of labour to farm operations:

|

Hours per week |

Respondents |

Percentage |

|

More than 40 hours per week |

34 |

19% |

|

30-40 hours per week |

30 |

17% |

|

20-30 hours per week |

38 |

21% |

|

10-20 hours per week |

35 |

20% |

|

Less than 10 hours per week |

40 |

22% |

- 67% of respondents have jobs “off-the farm” with a large number holding jobs in other agri-businesses such as merchant shops, insurance agencies and a high proportion working in veterinary, education and health services

- A third of returnees contribute 20 hours per week or more to farm activities, on top of other employment

- A large proportion, 41%, of those women who have jobs off the farm have used their income to subsidise farm expenses and/or to secure finance for the farm business – 13% stated that this happens regularly.

This highlights a clear issue for some local women living and working on farms in terms of financial autonomy and may reflect more profound underlying problems regarding the viability of local farm holdings, some of which rely on other sources of income, rather than productive output, to maintain operations.

Views on Women’s Role in Agriculture

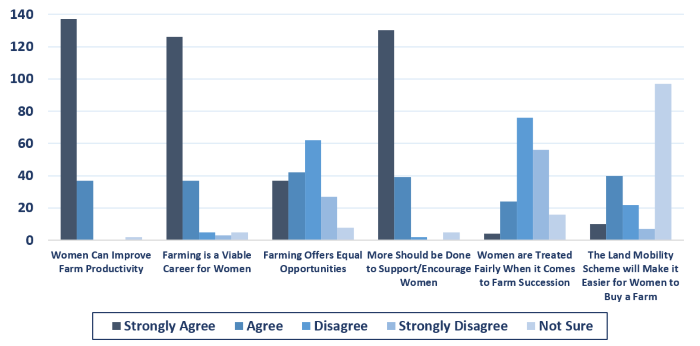

96. We asked to what extent respondents agreed with a number of statements in relation to women’s role within the agricultural sector:

- 98% of respondents Strongly Agree/Agree that women help improve farm productivity and no respondents Disagree with this statement

- 95% Strongly Agree/Agree that more should be done to support women to take up the running of farms

- 92% Strongly Agree/Agree that farming offers a viable career opportunity for women

- 50% Strongly Disagree/Disagree that farming offers equal opportunities for men and women

- Only 15% Agree to some extent that women are treated fairly when it comes to farm succession

- While 20% of respondents Agree that the Land Mobility Scheme will make it easier for women to take on ownership of farms, the majority of returnees are unsure about this

97. The data highlights that local women believe very strongly that women play a positive and productive role on local farm holdings and that engagement in the agricultural sector presents a viable career opportunity.

98. However, it is evident that the vast majority of local women advocate that more support mechanisms need to be put in place to enable women to take on leadership roles and to overcome some key barriers, including the consideration of women as prospective successors when it comes to farm inheritance.

99. Further, this information suggests that the agricultural sector may need to focus on initiatives to give women expanded opportunities for development in order to mitigate the perception that the industry does not provide equal opportunities for men and women, and to reenergise and promote the Land Mobility Scheme as a potential option for local women to take on farm ownership.

Barriers Experienced by Women

100. Returnees were given the opportunity to rank a number of statements regarding the often-reported challenges women face in order to gauge local women’s opinion about the relevant importance of these issues on a scale from 1 “Very Important” to 5 “Not Important at All”. The table below shows the “top” issues by average score:

|

Issue |

Average Score |

% Very Important |

|

Gaining ownership (succession planning) |

1.67 |

53% |

|

Caring responsibilities |

1.79 |

48% |

|

Lack of support from family |

1.86 |

43% |

|

Lack of confidence |

1.89 |

43% |

|

Under representation of women role models in the industry |

1.89 |

48% |

|

Gender bias within the industry |

1.94 |

49% |

101. This highlights that local women, by some margin, consider gaining ownership of farms and inheritance practices as the most important barrier they face in the sector.

102. The perceived obligation to undertake caring responsibilities both for children and older family members was also ranked very highly as this encumbers on the time available for women to engage in farm activities.

103. Respondents also scored “Lack of Support from Family” highly which may indicate a reluctance in some local families to encourage young women to adopt farming as a career path. Further, the lack of women role models within the sector was also highlighted as an important barrier.

104. Cultural attitudes in respect of perceived Gender Bias and that farming is a “man’s role” are also perceived as key barriers with approximately 50% of respondents considering this to be “Very Important.”

- We asked respondents what they think is the biggest challenge women face:

- Over 70% of respondents referred to cultural norms in terms of the local agricultural sector being a male-dominated industry and existence of a social stigma associated with women farmers.

Many returnees articulated that women are not respected as equals to men and therefore do not have the same opportunities in terms of access to land, finance and equipment as their male counterparts, which significantly constrains their ability to take on more prominent roles in the sector.

A high number of returnees explained that there is an underlying unacceptance of women farmers in some quarters which manifests itself in behaviours and practices which are not conducive to supporting women’s opportunities.

For example, respondents reflected experiences of receiving negative and judgemental comments from male farmers and/or their families when they expressed an interest in pursuing a career in farming.

We also heard from a number of respondents who specifically mentioned experiencing misogynistic and derogatory behaviour from men at local marts and auctions.

“One of the biggest challenges is that a lot of men think that women can’t do the job, I know from when I started off men didn’t want to rent land to me because I was a woman, at the very beginning at the sale yards/marts there were a few men that would have tried to push me out from bidding on animals as they though[t] a woman shouldn’t be there.”

“Women, especially young women, are not seen to be competent enough to run farms even if they have an education in the agricultural sector. As a woman in the agricultural sector, I frequently have men walk into the yard and immediately ask if my father or my husband is around.”

- Just under 18% of returnees reflected that expectations of women to be responsible for childcare (and other caring responsibilities) hinders opportunities, both in terms of a time commitment and, for pregnant women, participating in physically demanding tasks. Respondents also noted the health and safety risks for pregnant women working on farms in close proximity to livestock, chemicals and pesticides and animals in gestation.

“Women are seen to be the main care giver in the home which can greatly reduce time that can be spent on the farm”

- 28 respondents (16%) cited issues pertaining to physical demands which may preclude women from pursuing more substantive roles on farms – some returnees reflected that biological differences between men and women are a barrier in and of themselves, whereas others explained that women may need additional equipment to carry out duties, carrying a higher cost burden

- Another important challenge expressed by respondents is that, in large part due to the other barriers which women face in the sector, many women seeking to pursue a career in agriculture have low self-confidence which has a negative impact in terms of take up of opportunities and training which are available

“Not being valued or rewarded for the work which they do is leading low self-confidence.”

- 20 returnees specifically mentioned challenges in respect of inheritance and transition of farm ownership between generations. The predominant practice of leaving farm ownership to a son or other male relative fundamentally limits young women who may wish to pursue farming as a career from accessing and owning land

Measures to Address Challenges

106. Returnees were asked for their opinion as to what interventions could be put in place to support women in the sector.

107. The predominant theme is that there should be a focus on addressing the underlying “male-dominated culture” within the industry through education and awareness of all farmers, both men and women, of the changing composition of agricultural workforces in other places and the increasing role of women.

108. Further, showcasing the productivity and success of women-owned farms is perceived by respondents as an important way of dispelling and challenging the stereotypical views held by some living and working within the industry.

109. Relatedly, respondents articulated that it is important for leaders and representatives in the sector to challenge traditional behaviours and attitudes and “set an example” by demonstrating that agriculture openly accepts, and welcomes, women to enter jobs in the industry – this may be particularly important at gatherings and social events, such as at trade marts and auctions, where women have reported experiencing misogynistic behaviour.

110. In order to augment this, farm families need to be engaged with about the importance of early succession planning and considering all siblings within the family as potential successors, regardless of their sex.

“Biggest challenge to overcome is the stereotype of a women's role on a farm (paperwork, feeding calves etc), males and even some females consider some jobs on a farm to be for either a man or woman. It's difficult to change attitudes towards woman running farms and it will take years for women to be viewed as equal.”

111. Promotion of women within the industry is seen as very important to challenge social stigma and having more women in leadership and executive roles in local agricultural organisations as a means of promoting attitudinal change.

112. Further, a number of respondents noted that in recent years there has been an increased media profile showcasing women farmers and considered that this should be enhanced to identify “success stories” and highlight the talent, capability and productive output of women in the sector. This will not only challenge preconceived notions about women’s ability but may also help to encourage and inspire women to pursue a career in the industry.

“Promote women in farming making it easier to get into especially for women that are not from a farming background. An idea could be to have an organisation like young farmers but for women to get together to promote farming too”

113. The facilitation of events and training networks specifically for women, was highlighted as an important means of encouraging women to take on more active roles in the sector.

114. A high number of returnees expressed a lack of confidence to participate in pre-existing training schemes because they are predominantly attended by men and this can lead to feelings of anxiety and unease (for some).

115. Conversely the option of attending “women-only” events is viewed very positively as a way of facilitating a supportive environment for women to meet, train, share best-practice and develop their skills.

“Courses set aside specifically for women on farming as when men [are] at [a] course [it can be] intimidating for women to speak”

116. Other measures including providing targeted support grants specifically for women and exploring options for subsidisation of childcare in rural areas were highlighted as potentially important initiatives which would help to address some of the practical and financial barriers women experience.

Training and Education

117. Given that access to training is a fundamental enabler to support skills development and open up opportunities, respondents were asked for their views on what training and education may be put in place to support women in the sector. The Committee also examined the enrolment of students by sex at agricultural training colleges and the results are attached at Appendix 2.

118. While around 11% of respondents noted that women do not require any additional or different training opportunities to men, returnees reflected that there are a number of measures which would be of benefit:

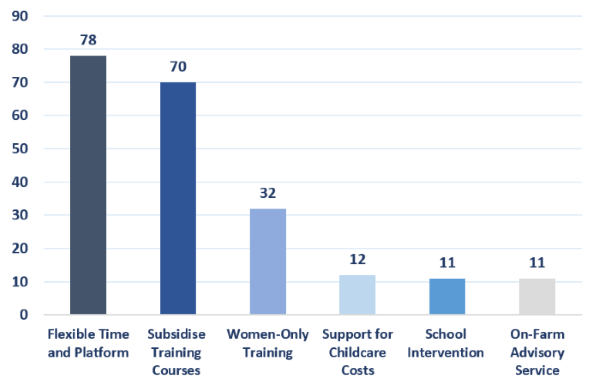

- Practical Training: around a third of respondents advocated for practical education and training in respect of on-farm tasks e.g., maintaining equipment and machinery, animal health issues and livestock care and information about how to complete paperwork and forms required for registering animals and applying for farm business schemes

- Business Management: to develop the skills and insights to help women manage holistically their farm including financial analysis, operations optimisation and service improvement

- Confidence Development: Provision of confidence and personal development training in order to mitigate feelings of anxiety and apprehension experienced by some women in the sector and instil self-belief to take on opportunities in the industry

119. In terms of measures that would encourage more women to partake in training/education, the feedback is displayed below:

Measures to Encourage Training Uptake

- A significant proportion of respondents advocated for flexible training options both in terms of provision of classes virtually and enabling access to these in the evening and at the weekends

- Many respondents called for grants as a means of subsidising training costs, particularly as training courses, especially for women living and working on a farm, are not considered a necessary expense

- A high number of respondents reaffirmed the value in facilitating women-only training courses and networks to provide a supportive environment for local women to come together, learn from each other and share knowledge and best-practice.

“Having flexible courses or having courses online would be a big encouragement for women that have other jobs or if they have a young family at home.”

“Funded courses would greatly encourage women to take up education as it would cause less financial stress on farm businesses and additionally flexible timetables that work around working woman farmers who already have busy lives but yet want to improve their knowledge and skills through education would prove extremely beneficial!!”

Farm Succession

120. One of the most pertinent issues in the agricultural sector is access to land and farm ownership. As outlined, due to the tradition of passing the family farm to a male heir or other male relative, women are far less likely to own farms compared to their male counterparts.

121. We asked respondents to describe the main issues that they perceive with farm succession practices and the key themes were as follows:

- There is a need to challenge directly the culture within local farming families that farms should be left to the son(s) or another male relative

- There is an overt fixation within some farming communities of “keeping the farm in the family name” and hence passing the farm to a son(s), even if they are less enthusiastic about managing the farm than a female sibling(s)

- Not considering daughters as potential successors may constrain opportunities for farm business diversification and development

- Older farmers should be encouraged to pass on farm ownership to the most suitable potential successor, regardless of their sex

- In many cases farm succession is considered a “taboo topic” which is not discussed amongst families and often decisions around transition occur when the incumbent owner is elderly

- Families need to be encouraged to have early, regular and open conversations about options for farm inheritance in order to ensure that potential successor(s) are identified, trained and developed to take on the family business

“Males in the family get first preference when the older generation are deciding to hand over the farm. Only if the boy is not interested will the girl be considered as a successor. The family name also comes into play, if a female succeeds the farm and marries the farm will no longer be in the original family name which may deter some from passing the farm to a female.”

Optimism About the Role of Women

122. Respondents were given the opportunity to state how optimistic they are about the role of women in agriculture both presently and in the future, and the results are shown in the below pie-charts:

123. This demonstrates that respondents generally have a more positive outlook about the future prospects for women in the agricultural sector than currently and a significantly higher proportion are Very Optimistic about women’s future role in the industry, 41% compared to 25%, as they believe that the introduction of measures to support women and challenge underlying cultural practices will have a positive impact.

10. Stakeholder Event

124. In order to support its considerations, the AERA Committee facilitated a virtual stakeholder event with a number of local women who had completed the survey and representatives from farming and other agri-related organisations on Thursday 3 February 2022: a total of 24 attendees participated.

125. The purpose was to facilitate multi-stakeholder discussion about the barriers faced by women in the local sector, and what measures might be usefully introduced to mitigate these.

126. At the outset of the session participants were asked to rank in terms of importance some of the often-reported challenges faced by women in agriculture with the results outlined below:

127. Attendees then discussed three questions in virtual “breakout rooms” relating to the Committee’s review:

- What do you think are the Top 3 challenges facing women in the local agricultural sector?

- How can these challenges be addressed?

- How can greater support for women help the agricultural sector meet its strategic challenges?

128. The feedback and notes from the breakout rooms were uploaded using the Mentimeter platform. The key points arising from the discussion of these questions are outlined below:

Challenges Facing Women

129.Attendees raised a wide range of issues, including:

- Due to the prevailing culture within the sector women can experience a lack of confidence and feelings of “not being able to do the job”

- Young women are often discouraged from pursuing farming as a career path by their family and a number of attendees shared their lived experience in this regard

- Women are fundamentally limited in terms of opportunities as a result of farm inheritance and are “only considered if you haven’t got a brother”

- The costs associated with childcare and provision in rural areas is an important barrier as women are expected to take primary responsibility for looking after the family

- Perinatal and pregnancy support: As self-employed workers there is no statutory maternity payment/leave for women farmers or support through pregnancy.

Due to the Health and Safety risks for pregnant women on farms, a women farm manager may have to incur additional costs of employing temporary labour to maintain operations while pregnant and in the initial weeks following childbirth.

- There is a lack of representation of women at senior positions within the agri-food sector

- Women can experience prejudicial attitudes when accessing finance for a farm business. For example, a participant recollected that a bank was unwilling to approve a loan for the farm unless her husband countersigned the application

- Women are subjected to both implicit and explicit misogynistic behaviour in the sector – for example some participants have experienced being offered a lower price for livestock at marts than male counterparts

Measures to Address Challenges

130. Participants suggested a number of practical and policy measures that could be introduced in order to help overcome the outlined challenges:

- Greater prominence should be given to “women role models” highlighting the talent and outcomes delivered by successful women farmers and leaders within the agri-sector. This should be showcased via social media, local journalistic activity and by farming and agriculture organisations

- Affirmative Action should be endorsed, supported and delivered in the sector by actively seeking women representatives on Committees and Executive-level Boards

- While some participants advocated that training/social events should be “gender neutral”, the prospect of Women-Only Knowledge Transfer Groups and education activities would be of benefit

- Delivery of an academically-led independent review, as has been carried out in Scotland, may facilitate greater insight and understanding of how women can be better supported

- Establishment of a multi-stakeholder advisory group comprising representatives from key organisations would be beneficial to inform, influence and educate the sector on how they can enhance opportunities for women

- The AERA Committee should lead the way in terms of promoting gender neutrality by seeking greater diversity in terms of witnesses and stakeholders it engages with in the sector

- Provision of financial support for women farmers during, and following, pregnancy would help to alleviate pressure and enable continuity of farming operations. This may help to encourage more women to pursue farming as a career

- It is up to both men and women within the industry, and at policy level, to “change the narrative” of agriculture as being a male-dominated sector

- The “image” of women in farming needs to be changed from making “tea and buns” to more accurately reflect the extent and diversity of activities which women undertake on local farms

- Language and information promoting farming education and training could be made more gender neutral to encourage women to apply and participate

- Unconscious Bias and/or Gender Equality training should be encouraged and facilitated in key organisations in the sector including at education facilities and representative groups

- There should be greater engagement with industry to promote how products, equipment and materials can be more appropriately branded and advertised to women

Supporting the Agriculture Sector

131. Attendees reflected on how enhancement of the role of women would benefit the agriculture sector to modernise and address some of the strategic challenges it faces:

- Having more women farmers will support more effective diversification on farms in the context of needing to change practices to meet Climate Change pledges

- Opportunity to regenerate and reinvigorate different ways of farming and to modernise techniques

- Encouraging and supporting more talented women into the sector could elevate NI’s agri-food output and international standing

- Women are potentially an untapped resource in terms of helping to address labour shortages across the agricultural industry

11. Recommendations

132. The AERA Committee recognises the many complex challenges which women face in terms of career progression within the agricultural sector and acknowledges that many of these are intertwined with cultural attitudes which will require persistent and long-term action to facilitate change.

133. However, based on the findings of its review, the Committee makes the following recommendations:

- The role of women within the agricultural sector should be formally acknowledged and celebrated through tabling of a Motion debate at the Assembly

- DAERA should, as part of the Knowledge Transfer Workstream of its Future Agricultural Policy, take specific actions to facilitate enhanced training and education for women in the sector to include:

-

- Design of programmes and course content which are specifically targeted at women farmers or those wanting to enter this role

-

- Ensure that provision of these programmes is flexible and made available online

-

- Establish a training subsidy grant specifically for women farmers to participate in courses (similar to provisions made in Scotland)

-

- Facilitation of “women-only” training forums similar to the Business Development Groups

- DAERA should, as part of the Generational Renewal Workstream, ensure that provision is made to educate farm owners about the benefits women can bring to farm businesses and the importance of considering the suitability of all potential successors, regardless of sex

- DAERA should consider commissioning an independent, academically-led review to understand further the issues affecting women in the agricultural sector

- DAERA should ensure that appropriate equality, diversity and unconscious bias training is provided to its staff and in its Arm’s Length Bodies

- DAERA should consider facilitating awareness training for key agri-food organisations about the benefits of Board diversity and increasing representation of women

- Organisations across the sector should embrace affirmative action and seek to promote and encourage women where possible

- Leaders across the industry, both men and women, should seek to “set an example” of expected behaviours and gender equality and should showcase this at events like agricultural marts and livestock auctions

- When promoting a new initiative, policy or project, agri-food organisations should consider how women can be promoted in communication strategies

- DAERA should explore the feasibility of options for providing support for women farmers during and after pregnancy

12. References

Ag Daily, 2017, 2017: Census of Agriculture – More Women Reported as Leaders on the Farm, 2017 Census of Agriculture: Women farmers better represented | AGDAILY

Anderson et.al, 2020, “Economic Benefits of Empowering Women in Agriculture: Assumptions and Evidence” The Journal of Development Studies, 57:2 pp 193-208

Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Agricultural Census historical data | Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (daera-ni.gov.uk)

Department for Agriculture, Food and the Marine, Ireland’s Summary of the Draft CAP Strategic Plan 2023-27

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs The Path to Sustainable Farming: An Agricultural Transition Plan 2021 to 2024 (publishing.service.gov.uk)

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Farming for the future: Policy and progress update (publishing.service.gov.uk)

Doss, 2018, “Women and Agricultural Productivity: Reframing the Issues” Policy Review, 36, pp 35-50

Doss et.al, 2018, “Women in Agriculture: Four Myths” Global Food Security, 16, pp 69-74

Doss, 2015, “Women and Agricultural Productivity: What does the Evidence Tell Us?” Discussion Papers Women and Agricultural Productivity: What Does the Evidence Tell Us? (core.ac.uk)

Eurostat, 2016, Farm indicators by agricultural area, type of farm, standard output, sex and age of the manager

Farmer’s Weekly, 2014, New Survey Shows Changing Role of Women on Farms, New survey shows changing role of women on farms – Farmers Weekly (fwi.co.uk)

Farming First, 2021, Rural Women: Policies to Help Them Thrive

Gebre et.al, 2021, “Gender differences in agricultural productivity: evidence from maize farm households in southern Ethiopia” Geojournal, 86, pp 843-864

Huffington Post, 2020, Women Who Farm are Finally Getting Counted, Women Who Farm Are Finally Getting Counted | HuffPost UK Environment (huffingtonpost.co.uk)

Northern Ireland Research and Statistics Agency, Women in Northern Ireland 2020 Labour Report Women in Northern Ireland 2020 Report

Scottish Government, 2017, Women in farming and the agriculture sector: research report

Smith et.al, 2021, “Farm Women: An Overview of the Literature in a UK Context” Royal Agricultural University Seminar Farm Women: An overview of the literature in a UK context. – Royal Agricultural University Repository (guildhe.ac.uk)

World Farmer Organisation Policy on Women in Agriculture

Women’s Agenda, 2019, How Women are Transforming Agriculture in Australia, How women are transforming agriculture in Australia (womensagenda.com.au)

Women in Agriculture: Progressive Scottish Farming, 2019, Final Report of the Women in Agriculture Taskforce

Women in Agriculture Stakeholders Group, 2021, Draft Interventions for CAP Strategic Plan

Appendix 1: “Breaking the Grass Ceiling”: Survey Results

Responses

In total there were 187 responses to the Committee’s survey, 181 of which were completed by women (97%) and six by men (3%)

Three women respondents do not currently work or live on a farm and/or were not raised on a farm and so there were 178 responses from the target demographic.

The details below encompass the answers from these 178 respondents.

Age Profile

The below graph shows the age profile of respondents with a fairly even distribution of responses from women aged between 16 and 64. The majority of respondents, 67%, were aged 45 or younger.

Respondent Age Range

Education and Training

There was an almost even split in the number of respondents who have completed education and training in relation to farm management (90) and those who have not participated in such activities (88).

Of those who have, the vast majority, 68%, hold a formal qualification in relation to agri-food management at various levels including Bachelor degree and technical certificates.

Participation in Farming Organisations

A large proportion, 47%, of respondents actively participate, or are associated with, local farming organisations and clubs, with the majority being members of the Ulster Farmer’s Union and/or the Young Farming Clubs of Ulster.

Type of Farm

We asked respondents to categorise the type of farm which they currently live/work on or on which they were raised (if applicable).

The below graph illustrates the responses with a fairly even distribution of farm holding types represented between Cattle/Sheep, Dairy and Mixed operations:

Type of Farm

Farm Location

In terms of regional representation, we received responses from women living or working on farms in all counties and the vast majority (70%) reside in Counties Antrim, Down and Tyrone:

Respondent Counties

Farm Ownership

The vast majority of respondents (83%) outlined that a man owns the farm on which they work or live. While not unexpected, this figure is lower than the DAERA agricultural census data that approximately 95% of principal farmers in NI are men.

This suggests that the respondents to the survey disproportionately represent farms with women owners and therefore are not entirely reflective of the total agricultural workforce, or there could potentially be more farms owned/controlled by women than is currently captured through the census data collation methodology.

Decision-Making

We asked respondents about on-farm decision making and 75% of returnees outlined that a man makes most of the decisions on their farm.

We also asked how much say respondents feel that they have in terms of farm decisions: 62% told us that they have “some say” and 23% consider that they have “little to none.”

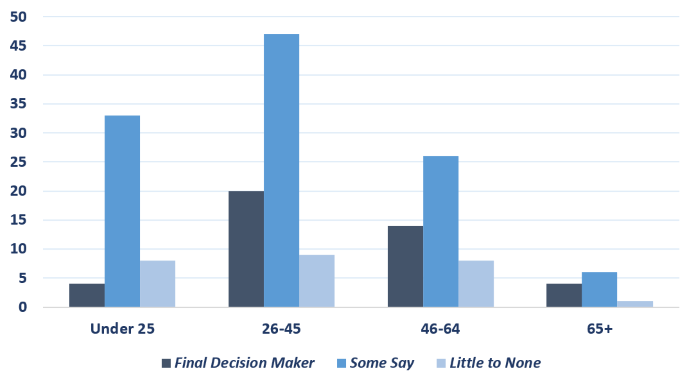

The extent to which respondents feel they have influence over farm decision making varies across age ranges with relatively more younger women believing that they have little to no say than other age bands, and the highest proportion of “Final Decision Makers” aged between 46 and 64.

This may reflect issues in terms of inheritance practices in that women may be more likely to take ownership of farms in later life in the absence of a male heir, when an elderly parent passes away.

Farm Decision-Making by Age

Idea for Change

Respondents were given the opportunity to state if an idea they had to change or diversify farm operations would be supported.

The vast majority of returnees, 70% believed that their idea would be supported, 13% felt that it would not be and 16% were unsure.

Respondents articulated that a number of factors may influence whether or not a proposition would be taken forward including the potential profitability and viability of the initiative and the extent of experience they have.

Further, a number of returnees intimated that ideas for change put forward by men living/working on a farm are more readily supported than those suggested by women:

“Depends on viability, profitability, experience and evidence”

“The farm is mainly run by the men of the family, but being a girl, I make sure I’m heard and if something isn’t working, I will make sure it’s sorted”

“Sometimes yes, it is heard and understood, although if it came from another man it would [be] listened to better.”

“Depends how big the change is and if others can see the benefits. A small change such as changing lambing period maybe yes but changing to another enterprise for example then maybe not”

“Depending on the idea and the decision. I feel in most cases this is only fair as I farm in partnership with my brother and father so no matter who comes up with the idea everyone needs to be ok with it”

On-Farm Role

We asked respondents about the extent of their input on their farms and what kind of duties they undertake.

The overwhelming majority of returnees, 98%, regularly participate in farm activities and just under a third regularly complete both practical “hands-on” tasks in addition to “supportive” jobs such as completion of paperwork and form-filling.

On-Farm Role

The diversity and range of activities carried out by women who completed the survey is illustrated in the below comments from respondents:

“I help at lambing time, fencing, dosing sheep, cleaning out the sheds as well as farm paperwork”

“Daily milking, rearing calves, feeding livestock, bookwork, lambing sheep and care of lambs, general livestock care i.e., dosing weighing etc, and other general farm duties as required”

“I am the back bone of the farm I do every job on the farm on a day to day running to make sure it runs as smoothly as possible...My jobs range from calving cows, lambing ewes, slurry spreading, farmyard manure spreading, rolling, mowing, tedding & baling all the silage/haylage & hay for the livestock to feed them over the winter months, then Drawing and stacking off round bales, dosing & all the general day to day things to do with all the livestock.”

“I complete milking of the cows twice daily, as well as making diet feeds for the cows, I also scrape and bed cubicles. In the summer time I put in the grass which includes mowing, raking and lifting or baling and wrapping. I also help with the rearing of calves and administer medicine if cattle are sick. As well as outside jobs I complete most the farm paper work as well.”

One hundred and sixteen respondents stated that they are primarily responsible for specific activities in the farm businesses:

- Paperwork, form completion and other administration duties: 37%

- Some aspect of livestock husbandry: 29% – over half of these returnees said that they are responsible for lambing/calving support or giving medication

- Both administration and practical duties: 23%

This demonstrates that a significant proportion, 25%, of the women who responded to the survey have primary responsibility for administration activities on their farms and whilst a significant number take the lead on certain aspects of livestock management, these tend to be less physically intensive tasks compared to manoeuvring, catching and controlling animals.

The table below shows the amount of time, on average, respondents to the survey spend per week on farm work, with just under a fifth working more than “full-time” hours and the majority contributing over 20 hours of labour to farm operations:

How much time do you spend on farm work on average?

|

Time spent on farm work |

Respondents |

Percentage |

|

More than 40 hours per week |

34 |

19% |

|

30-40 hours per week |

30 |

17% |

|

20-30 hours per week |

38 |

21% |

|

10-20 hours per week |

35 |

20% |

|

Less than 10 hours per week |

40 |

22% |

Off-Farm Employment

We asked respondents if they have another form of employment away from the farm on which they live/work.

The vast majority, 67%, have jobs in other sectors with a large number holding jobs in other agri-businesses such as merchant shops, insurance agencies and a high proportion of returnees working in veterinary, education and health services.

Just under a third of all respondents, 57, contribute 20 hours per week, or more, on average to farming activities in addition to holding jobs off the farm.

This reflects a significant amount of discretionary labour and time allocated to farm operations over and above individuals’ regular employment.

A large proportion, 41%, of those women who have jobs off the farm have used their income to subsidise farm expenses and/or to secure finance for the farm business – 13% stated that this happens regularly.