Committee for Finance and Personnel Report (2007-2011 Mandate)

Second Report on the Inquiry into the Role of the Northern Ireland Assembly in Scrutinising the Executive's Budget and Expenditure

Second-Report-on-the-Scrutiny-of-the-Budget.pdf (3.98 mb)

Session 2009/2010

Fourth Report

Committee for Finance and Personnel

Second Report on the

Inquiry into the Role of the Northern Ireland Assembly in Scrutinising the Executive's Budget and Expenditure

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the Committee

Relating to the Report, Written Submissions, Memoranda and the Minutes of Evidence

Ordered by The Committee for Finance and Personnel to be printed 30 June 2010

Committee for Finance and Personnel

Report: NIA 66/09/10R

Committee Powers and Membership

Powers

The Committee for Finance and Personnel is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, Section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 48. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Department of Finance and Personnel and has a role in the initiation of legislation.

The Committee has the power to;

- consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- approve relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee Stage of primary legislation;

- call for persons and papers;

- initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister of Finance and Personnel.

Membership

The Committee has eleven members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, with a quorum of five members.

The membership of the Committee since its establishment on 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Ms Jennifer McCann (Chairperson)

[2] Mr David McNarry** (Deputy Chairperson)

[3] Mr Jonathan Craig***

Dr Stephen Farry

Mr Simon Hamilton

Mr Fra McCann

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Mr Adrian McQuillan

Mr Declan O'Loan

[1] Mr Ian Paisley Jnr*

Ms Dawn Purvis

[1]* Mr Ian Paisley Jnr replaced Mr Mervyn Storey on the Committee on 30 June 2008

Mr Ian Paisley Jnr resigned from the Assembly with effect from 21 June 2010.

[2]** Mr David McNarry replaced Mr Roy Beggs on the Committee on 29 September 2008

[3]*** Mr Jonathan Craig replaced Mr Peter Weir on the Committee on 13 April 2010

Contents

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms used in the Report iv

Executive Summary 1

Key Conclusions and Recommendations 2

Introduction 5

Consideration of the Evidence 6

Response to the Department of Finance and Personnel Review of the

NI Executive Budget 2008-11 Process

Action Plan for Implementing the

Department of Finance and Personnel Recommendations

Other Issues and Next Steps:

Cross-departmental working

Independent Budget and Financial Scrutiny

Access to Information

Stage 2 of the Inquiry: Resources

Stage 3 of the Inquiry: Review of Monitoring Rounds

List of Appendices to the Report 23

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings Relating to the Report 27

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence 53

Appendix 3

Memoranda and Papers from the Department of Finance and Personnel 81

Appendix 4

Assembly Statutory Committee Submissions 171

Appendix 5

Assembly Research Papers 199

Appendix 6

Other Papers 309

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms used in the Report

CED Central Expenditure Division

CFG Central Finance Group

CSR Comprehensive Spending Review

DCAL Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

DEL Departmental Expenditure Limit

DFP Department of Finance and Personnel

DHSSPS Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety

DOE Department of the Environment

EDP Efficiency Delivery Plan

EQIA Equality Impact Assessments

EYF End Year Flexibility

GB Great Britain

HLIA High Level Impact Assessment

HM Her Majesty's

IMF International Monetary Fund

ISNI Investment Strategy for Northern Ireland

MLA Member of the Legislative Assembly

MoU Memorandum of Understanding

NDPB Non-departmental public body

NI Northern Ireland

OFMDFM Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister

PfG Programme for Government

PFI Private Finance Initiative

PSA Public Service Agreement

PSD Public Spending Directorate

ROSC Report on the Observance of Standards or Codes

RRI Reinvestment and Reform Initiative

SIB Strategic Investment Board

SWOT Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats

UK United Kingdom

Executive Summary

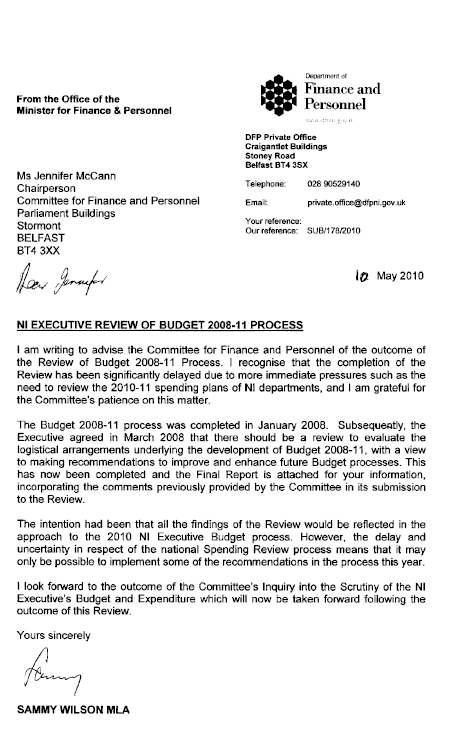

The Committee for Finance and Personnel commenced its Inquiry into the Role of the Northern Ireland Assembly in Scrutinising the Executive's Budget and Expenditure in July 2008. Intended to be conducted in stages, the aim of the inquiry is to maximise the Assembly's contribution to the Northern Ireland budget process and enhance the role of Assembly statutory committees and Members in budget and financial scrutiny. The first report of the inquiry, published in October 2008, formed the Committee's submission to the Department of Finance and Personnel's Review of the Northern Ireland Executive Budget 2008-11 Process, which reported in May 2010. This second report of the inquiry is the Committee's response to the recommendations arising from the Department's review.

The Committee took oral evidence from Department of Finance and Personnel officials on the outcome of the Department's review. To help inform its consideration of the review report, the Committee commissioned research on budget processes and structures in other legislatures. The Committee also received submissions from other Assembly statutory committees.

The Committee considers that a number of the principles arising from both the Department's review and the Committee's inquiry could form the basis for modelling the future budget processes in terms of engagement, openness and transparency. In particular, the Committee notes the focus afforded to increasing the linkage between the Programme for Government and the Budget, and enhancing and encouraging engagement between departments and their Assembly committees and key stakeholders. While welcoming the Department's recommendations that seek to make improvements in this regard, the Committee has identified where it considers these can be developed further.

The Committee found that a number of the recommendations were contingent on access to financial information and specialist support to assist the scrutiny by the Assembly and its committees; these issues will be considered further as part of the next stage of this inquiry. In the longer term, there is a case for the Assembly considering how its financial scrutiny system, including committee structures, could be reformed for enhanced effectiveness.

The Committee is concerned that a lack of clarity remains on the shape, frequency and duration of future budget cycles. Moreover, given that the action plan to implement the Department's recommendations was not yet agreed at Northern Ireland Executive level at the time of this report, there are doubts as to whether any or all of the recommendations can be agreed and implemented in time for the Budget 2010 process. The Committee considers that, as a necessary next step, the Assembly and Executive must agree a template for future budget processes which is based on good practice principles, including those outlined in this report.

The Committee has identified a number of key findings and recommendations from the evidence and these, together with the issues raised by the other statutory committees, are intended to inform the establishment of a regularised budget process moving forward.

Key Conclusions and Recommendations

1. The Committee firmly believes that there should be clear, visible linkage between the PfG, PSA targets and budget allocations, and therefore welcomes, as a step in the right direction, the DFP recommendation that "an exercise should be conducted at the start of the next Budget process to seek to determine the level of public expenditure underpinning actions to deliver each Public Service Agreement in the Programme for Government (PfG)." (Paragraph 12)

2. Given its previously expressed concerns around the complexity of the current PfG and PSA framework, and in light of both the increased need for priority-based budgeting and the apparent move away from the system of PSAs in Whitehall, the Committee calls on the Executive to review the performance and accountability framework for NI departments, with the aim of establishing a more transparent and robust system for measuring and monitoring the relationship between public sector inputs, outputs and outcomes. (Paragraph 13)

3. Whilst recognising that the availability of resources will have a bearing on the targets underpinning the PfG, the Committee is strongly of the view that budget allocations should be driven by priorities and not the other way around. The Committee concurs with the DFP view that "there should at least be a clear indication of broad priorities at the beginning of the Budget process" and that the development of the PfG should precede the Budget. (Paragraph 17)

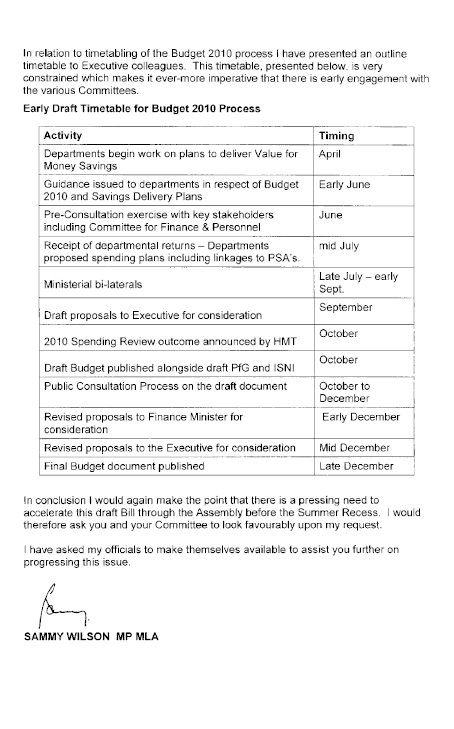

4. Whilst it considers that the setting of a clear timetable to include key milestones at the start of each budget process is of vital importance, the Committee believes that clarity is required on the shape, frequency and duration of future budget cycles. In noting that the Budget 2010 process will develop departmental spending plans for the four-year period from 2011-12 to 2014-15, the Committee recommends that a regularised annual budgetary review process is established within this framework, with a pre-determined timetable, to enable the Executive and Assembly to make interim reappraisals of departmental allocations against progress in delivering PfG priorities and savings. (Paragraph 22)

5. The Committee calls on DFP to build in adequate provision for the Executive decision-making process and for the Assembly calendar when developing future budgetary timetables, with a view to ensuring sufficient time for engagement with the Assembly and other stakeholders. (Paragraph 25)

6. Though strongly supportive of the DFP recommendation that "there should be early and more structured engagement between departments and Assembly Committees setting out the key issues and pressures facing NI Departments", the Committee considers that decisive measures are needed to put this into practice. (Paragraph 32)

7. The Committee concurs with the recommendation from the Education Committee that DFP should take the lead in developing "standard guidance to NI departments on the timing and provision of relevant information to Assembly statutory committees" and that this should be agreed at Executive level, with departmental compliance being monitored by DFP in consultation with the Assembly statutory committees. (Paragraph 32)

8. In noting that the timetable for the Executive's Budget 2010 process has an end date of "late December", the Committee calls on DFP to offer flexibility on this deadline to provide sufficient time for engagement with Assembly committees and the wider public. The Committee found that good practice would indicate a period of 2 – 4 months should be provided for in this regard. The Committee considers this feasible given that the Budget 2008-11 was not agreed in the Assembly until 29 January 2008 and, more recently, the Revised 2010-11 Spending Plans were not agreed by the Assembly until 20 April 2010. (Paragraph 33)

9. The Committee considers that greater influence can be brought to bear on spending plans at the earlier stages in the process, and therefore is supportive of the DFP recommendation that "there should be earlier engagement with key stakeholder groups by departments as part of the Budget process". However, the Committee believes that care should be taken by departments to ensure that a wide spectrum of stakeholder interests are included at this time to ensure that it is not the larger interest groups only that have the opportunity to influence the spending plans. (Paragraph 37)

10. In noting the DFP proposal that it "should take the lead role from the Strategic Investment Board (SIB) in developing capital investment allocations in the Budget process", the Committee intends to take further evidence from the Department and also to invite separate evidence from SIB, to enable it to reach an informed position on this issue. There will also be a need to liaise further with the Committee for OFMDFM on the outcome of this work. (Paragraph 40)

11. The Committee supports the DFP recommendation that "every departmental spending proposal should clearly state the impact on the respective PSA target, if successful." However, the Committee also believes that this linkage between spending and PSA targets at the bidding stage should extend to the reporting stage, whereby the End Year Delivery Reports would enable performance to be tracked at a departmental level in terms of inputs, outputs and outcomes. (Paragraph 44)

12. The Committee agrees with the DFP recommendation that "the Draft Budget document should include an easy to read summary at the start of the document." (Paragraph 48)

13. The Committee further recommends that all relevant financial documents, including Budgets, Estimates and Resource Accounts, are simplified and harmonised to increase transparency and enhance the relationship between allocations and performance and also to ensure that they are more readily scrutinised by Assembly committees and accessible to the wider public. (Paragraph 48)

14. The Committee welcomes the DFP recommendation that "the full list of prioritised spending proposals submitted by departments as part of the draft Budget process should be published alongside the draft Budget document, including details of which proposals will be funded from the draft Budget allocations." The Committee notes that this aligns with the conclusion in its Report on the Executive's Draft Budget 2008-2011, published in December 2007, that "there would be benefit, in terms of transparency and scrutiny, from fuller and more standardised information on departments' bids and their outcomes being published as part of the draft Budget process. (Paragraph 51)

15. The Committee supports the DFP recommendation that "Departments should publish the High Level Impact Assessment for each spending proposal." The Committee also recommends that departments should publish the results of the equality screening undertaken in respect of each spending proposal in fulfilment of the duties imposed by Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998. (Paragraph 53)

16. The Committee would reiterate the recommendation made in its submission to the DFP review that supporting documents, such as draft PSAs and draft delivery plans for efficiencies and investments, should be published alongside the draft Budget, as this would inform committee scrutiny and could provide some assurance regarding deliverability. Whilst recognising that such draft supporting documents may require development before being finalised, the Committee believes that, with careful planning and given the proposal to develop the PfG in advance of the Budget, it is reasonable to expect these draft documents to accompany the draft Budget. (Paragraph 55)

17. The Committee does not support the DFP recommendation that "Assembly Committees should have the lead role in the consultation on the Executive's draft Budget proposals, with responses to the Executive co-ordinated by the Committee for Finance and Personnel." In noting that other statutory committees have also voiced concern with this proposal, the Committee believes that this would be an inappropriate role for Assembly committees to fulfil, especially given that they would not have the authority to act on the outcome of such consultation. (Paragraph 59)

18. The Committee notes with interest the recommendations from DFP that "in responding to the draft Budget, any proposal to increase spending on a particular service by a Committee should be accompanied by an equally detailed proposal as to how this could be funded"; and that "the Committee for Finance and Personnel, in responding on behalf of all the Committees, should identify whether it views the funding proposal to be realistic or not." The Committee, however, sees such an approach as more applicable in the context of a reformed system of Assembly financial scrutiny; whereby departmental committees would have access both to the necessary financial information held by departments and to additional specialist support and where a central budget committee existed with the requisite powers. The Committee believes that such a scrutiny model warrants more detailed consideration by the Assembly in the future. (Paragraph 66)

19. The Committee is, in principle, supportive of the DFP recommendation that "the Final Budget Statement and debate should be combined with the Main Estimates process" as this should make for a more streamlined and harmonised approach. That said, the Committee looks forward to being consulted on the detail of this proposal and firmly believes that such change should only be made in the context of a settled future budget process, which will require to be agreed between the Executive and the Assembly. (Paragraph 71)

20. The Committee looks forward to receiving the action plan for implementing the DFP review recommendations and expects that this will be updated to take account of this co-ordinated response on behalf of the Assembly statutory committees. (Paragraph 72)

21. The Committee continues to place high importance on cross-departmental working, not only in terms of policy and service delivery but also in the context of improved efficiency and effectiveness across the public sector. As such, the Committee believes that the Executive must bring forward proposals for improving the arrangements both for promoting and funding collaborative working by departments and other public bodies and for measuring and monitor performance in this area (Paragraph 74)

22. The Committee considers that it would be good practice both for the Executive's draft Budget to be accompanied by some level of assessment of the fiscal sustainability of the associated policies and for some form of independent external scrutiny to be applied to the Executive's spending proposals. On this latter issue, as part of its Stage 2 Inquiry report, the Committee will be examining the potential for elements of this independent external scrutiny function to be exercised cost-effectively through the reconfiguration and greater use of the existing options for specialist support to Assembly committees and Members in undertaking financial scrutiny. (Paragraph 77)

23. The Committee considers that there is a need for DFP, at the earliest opportunity, to set out its up-to-date position on the future approach to in-year monitoring, including the option of establishing a contingency fund. It will be important that the most effective system for maintaining the optimum allocation of resources towards the Executive's highest priority spending areas is put in place in time for the implementation of Budget 2010. (Paragraph 87)

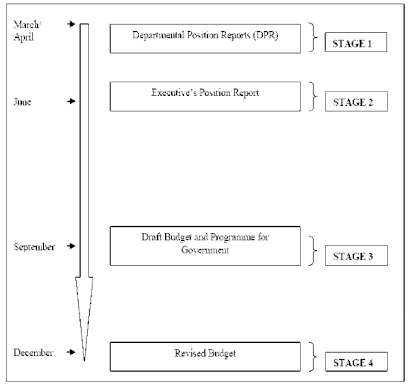

Introduction

1. In July 2008, the Committee for Finance and Personnel agreed terms of reference for an Inquiry into the Role of the NI Assembly in Scrutinising the Executive's Budget and Expenditure. The aim of the inquiry would be to maximise the Assembly's contribution to the Executive's budget process and to enhance the role of the Assembly statutory committees and Members in budget and financial scrutiny. It was also intended that the inquiry would run in tandem with the review of the Executive's budget process being undertaken by the Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP), the terms of reference for which had been agreed in May 2008 (Appendix 3). The Committee agreed that the first part of Stage 1 of its inquiry would contribute to the DFP review, and published its Report, Stage 1: Submission to the Review of the Northern Ireland Executive's Budget Process, in October 2008.

2. Since that time, the Committee has pressed for completion of the DFP review, which it believed should assist in providing clarity on the way forward for the future budget process. In the absence of the completed DFP review, the Committee was not in a position to press ahead with the second part of Stage 1 of its inquiry, which was to consider and respond to the findings from the DFP review. Although it was initially intended to have been concluded in late 2008, DFP has, in correspondence with the Committee, cited a number of reasons for the lengthy delay in completion of the review, including: managing the in-year monitoring process; the Strategic Stocktake that was undertaken in 2008; and the Review of 2010-11 Spending Plans for NI Departments in late 2009/early 2010.

3. Following its completion, DFP officials gave evidence on the Review of Northern Ireland Executive Budget 2008-11 Process at the Committee's meeting on 12 May 2010, and this has enabled the Committee to proceed with this part of its inquiry. The main recommendations from the DFP review are listed below, and the full report is provided at Appendix 3. The Official Report of the evidence session of 12 May 2010 is at Appendix 2. At the time of agreeing this inquiry report, the Committee understands that the DFP Review Report has not been agreed at NI Executive level.

4. To assist in its deliberations, the Committee commissioned a paper from Assembly Research to consider the NI budget process in light of international good practice in executive-legislature relations and budget processes in other jurisdictions, and this paper was considered by the Committee on 12 May 2010. During the discussion on the research paper, the Committee commissioned a further paper examining the concept of a central budget committee for the Assembly. Both papers are provided at Appendix 5.

5. To help inform this report, the Committee invited comments on both the DFP Review Report and the Assembly research paper, Considerations for Reform of the Budget Process in Northern Ireland, from the other Assembly statutory committees. The responses from the other committees have been referenced below, with the full submissions included at Appendix 4. In addition, the Committee requested the Department's comments on the Assembly research paper, the response to which is at Appendix 3.

Consideration of the Evidence

Response to the DFP Review of the NI Executive Budget 2008-11 Process

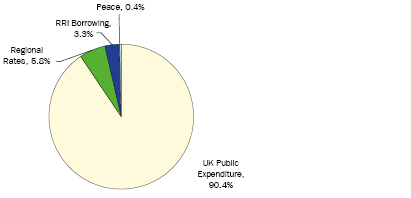

6. The DFP review was undertaken "with a view to making recommendations to improve and enhance future Budget processes."[1] The Terms of Reference tasked the review to consider, inter alia, the relationship between Budgets and the Programme for Government (PfG), engagement with departmental Assembly committees and the management of capital investment. In addition to seeking input from key stakeholder organisations, such as those representing the community and voluntary sector, business organisations and Trade Unions, the review considered the current budget processes in Scotland and Wales. As mentioned above, the Committee made a submission on behalf of the Assembly to the DFP review, which formed part 1 of Stage 1 of this inquiry.

7. The main findings from the Review Report noted that "there was a significant degree of commonality in the issues raised by various stakeholders", for example with regard to the need to consult with key stakeholders as early as possible in the Budget process. It also noted significant differences in views in respect of some issues, such as the length of the process which was judged by some as being too short and others too long. The key recommendations proposed, which DFP considers will improve the Budget process moving forward, are set out below.

|

(i) The DFP review recommended that: "An exercise should be conducted at the start of the next Budget process to seek to determine the level of public expenditure underpinning actions to deliver each Public Service Agreement in the Programme for Government (PfG)." |

8. The DFP review found that the absence of a clear link between the PfG and Budget had restricted scrutiny of the Budget proposals. The information provided by an exercise such as that recommended would therefore give a baseline against which to compare spending proposals. However, during the evidence session, Departmental officials advised that while this is a highly desirable aim, it should ideally be commenced at the start of a calendar year and, as such, would be delayed in terms of the anticipated Budget 2010 process.

9. In their responses to the Committee, a number of statutory committees indicated that they believe it is important that clear links are established between the Budget, PfG priorities and the delivery of PSA targets; measures to make improvements in this regard are therefore to be welcomed.

10. On 20 January 2010, the Committee received a briefing from Assembly Research on Methods of Budgeting (see Appendix 5). It noted that, whilst public sector budgeting in NI, in line with GB, typically relies on the incremental approach, this method of budgeting can obscure an overall picture of performance for managers and Ministers. Zero-based budgeting, on the other hand, starts from the basis that no budget lines should be carried forward from one period to the next simply because they occurred previously. This process ensures that organisations provide business justification for each activity they undertake. Activities are then ranked in order of priority and this is where resources are focused.

11. The Assembly research outlined several case studies where the principles of zero-based budgeting have been applied. Whilst not without its own difficulties, these case studies illustrate that a phased implementation of a zero-based budgeting approach following a full business case justification, can also have a positive impact on the measurement, and accountability, of performance. The research also outlined a number of alternative budgeting techniques including:

- Priority-based budgeting;

- Decision conferencing;

- Planning Programming budgeting system;

- Performance-based budgeting; and

- Participatory budgeting.

12. In its Report on the Executive's Draft Budget 2008-11, published in December 2007, the Committee called for closer alignment between the Budget and PfG, and repeated this call in its submission to the DFP review in October 2008. The Committee considers this should have been the case as a matter of course. The Committee firmly believes that there should be clear, visible linkage between the PfG, PSA targets and budget allocations, and therefore welcomes, as a step in the right direction, the DFP recommendation that "an exercise should be conducted at the start of the next Budget process to seek to determine the level of public expenditure underpinning actions to deliver each Public Service Agreement in the Programme for Government (PfG)."

13. Related to this issue, in its recent report on public sector efficiencies, the Committee has noted that the current PfG and PSA framework is cumbersome and overly complex at a time when priorities must be re-considered during this period of exceptional budgetary constraint. Moreover, the Committee notes that the need to simplify the monitoring of performance is a view also expressed in the guidance issued by HM Treasury in advance of the Spending Review, due to be completed in the autumn. The new Westminster Government has ended what it calls the "complex system of Public Service Agreements" in respect of Whitehall departments. The new approach will "include the publication of departmental business plans showing the resources, structural reforms and efficiency measures that will need to be put in place to protect and improve the quality of key frontline services while spending less."[2] Given its previously expressed concerns around the complexity of the current PfG and PSA framework, and in light of both the increased need for priority-based budgeting and the apparent move away from the system of PSAs in Whitehall, the Committee calls on the Executive to review the performance and accountability framework for NI departments, with the aim of establishing a more transparent and robust system for measuring and monitoring the relationship between public sector inputs, outputs and outcomes.

|

(ii) The DFP review recommended that: "The PfG should be developed to a timetable slightly in advance of the Budget." |

14. While recognising that it would not be possible to finalise targets underpinning priorities until Budget allocations are finalised, the review recommended that an indication of broad priorities should be available at the start of the Budget process to provide a degree of clarity on spending proposals. In their oral evidence to the Committee, the Departmental officials confirmed that, as the First Minister and deputy First Minister are responsible for the PfG, this recommendation is subject to their consideration and agreement.

15. Again, a number of statutory committees indicated their support for this recommendation, as it will serve to further define and strengthen the link between the PfG and Budget. In particular, both the Committee for Agriculture and Rural Development and the Committee for Regional Development stressed that the Executive's priorities should drive the budget, not the other way around. In addition, the Committee for Regional Development further recommended that

"the costs and achievements/ outcomes against each PSA be published in order that Committees have the opportunity to evaluate the prioritisation of Departmental bids as well as allocations against each of its departmental PSAs, when considering both the draft budget and draft PfG."

16. The Committee for OFMDFM considered that Equality Impact Assessments (EQIA) should also be completed in advance of the Budget.

17. Whilst recognising that the availability of resources will have a bearing on the targets underpinning the PfG, the Committee is strongly of the view that budget allocations should be driven by priorities and not the other way around. The Committee concurs with the DFP view that "there should at least be a clear indication of broad priorities at the beginning of the Budget process" and that the development of the PfG should precede the Budget.

|

(iii) The DFP review recommended that: "A clear timetable setting out the key milestones should be made publicly available at the start of each Budget process." |

18. Respondents to the DFP review considered that a clear timetable for the Budget process should be agreed and published. The review found that there was a perception that the draft Budget was a fait accompli; setting a timetable and raising awareness of the key milestones would help ensure that stakeholders would be fully aware of when to best influence spending proposals.

19. In its response to the Committee, the Regional Development Committee contended that it is not a perception but a reality that the draft Budget is a fait accompli. It was therefore supportive of this recommendation, as were the committees for OFMDFM, Education, Employment & Learning and Health.

20. The absence of a settled budget process has been of particular concern to the Finance and Personnel Committee for some time. Since the publication of its Report on the Draft Budget 2008-11, the Committee has repeatedly sought clarity on the future budget process, in both written correspondence with the Department and the Minister, and also during evidence sessions with Departmental officials. In its recent Report on the Review of 2010-11 Spending Plans for NI Departments, the Committee called for "the urgent establishment of a formal process for Assembly scrutiny of future Executive Budgets and expenditure."

21. The Committee is aware that the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) note on the Role of the Legislature in Budget Processes contends that nearly all countries adopt budgets annually.[3] Assembly research found that good practice indicates that a regularised annual process with a pre-determined timetable should be adhered to. In recognising the need for strategic planning, an annual budget should not cover a period of one year only, but should also include budget forecasts for at least the medium term (normally a three-year period). In this regard, the Committee notes that the recent DFP guidance to departments on Budget 2010 states that the process "will involve the development of the spending plans for NI departments covering the four year period 2011-12 to 2014-15".[4] It is unclear to the Committee, however, whether this will, in effect, mean that a quadrennial process is now envisaged, or whether the Executive instead intends to establish a process for reviewing the departmental allocations on an annual basis, or at some other point during the four-year period which would involve Assembly input.

22. Whilst it considers that the setting of a clear timetable to include key milestones at the start of each budget process is of vital importance, the Committee believes that clarity is required on the shape, frequency and duration of future budget cycles. In noting that the Budget 2010 process will develop departmental spending plans for the four-year period from 2011-12 to 2014-15, the Committee recommends that a regularised annual budgetary review process is established within this framework, with a pre-determined timetable, to enable the Executive and Assembly to make interim reappraisals of departmental allocations against progress in delivering PfG priorities and savings.

23. The Committee is aware that the timing of Executive decisions on financial issues will have a bearing on budget timetables. In evidence to the Committee on 11 February 2010, the Finance Minister suggested that delays in achieving Executive decisions had resulted in a truncated process in respect of the Review of 2010-11 Spending Plans of NI Departments. The Committee recognises that such delays can have an adverse impact in terms of the time available for engagement with the Assembly and the wider public.

24. Also in terms of timetabling, the Committee acknowledges that the calendar for Assembly sessions is an additional factor which has to be taken into account, both in terms of the process for setting future budgets and as regards in-year monitoring. On the latter, for example, DFP recently agreed to extend the deadline for departmental returns for the September Monitoring Round from 3 September to 10 September to facilitate pre-consultation with Assembly statutory committees following summer recess. The Committee has welcomed the flexibility shown by the Department in this regard.

25. In acknowledging the competing considerations outlined above, the Committee calls on DFP to build in adequate provision for the Executive decision-making process and for the Assembly calendar when developing future budgetary timetables, with a view to ensuring sufficient time for engagement with the Assembly and other stakeholders.

|

(iv) The DFP review recommended that: "There should be early and more structured engagement between departments and Assembly Committees setting out the key issues and pressures facing NI Departments." |

26. The DFP review noted that the timetable in respect of the Budget 2008-11 was truncated, and as a result there was no opportunity for early engagement with Assembly committees, and also with regard to the production of departmental and Executive position reports. The review contended that early, structured engagement with Assembly committees would essentially obviate the need for the publication of position reports in future budget processes. The review further considered that information supplied to committees will, through time, become more structured and standardised as a result of early engagement with departments in the Budget process.

27. In its response to the outcome of the DFP review, the Committee for the Environment stated that it would welcome any opportunity for more timely engagement, while the Committee for Employment and Learning considered this to be a key element of budget preparation. The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure cited previous difficulties it had encountered with processes regarding the Budget 2008-11 and the Review of 2010-11 Spending Plans. It considered that proper consultation is necessary to enable the Committee to make a meaningful response to the draft Budget. The committees for Health and OFMDFM were also broadly supportive of this recommendation.

28. As noted above, the Agriculture and Rural Development Committee considered that strategic direction should be the primary driver for a budget and, in that respect, has also requested early engagement with its Department in the development of strategic plans. Contrary to the DFP review apparently advocating against the publication of position reports, the Committee for Regional Development believes that they provide early opportunities for committees to explore the budgetary position faced by departments. That Committee also considered that engagement should be continual and ongoing, rather than taking place only at specific times in the process.

29. In its response, the Committee for Education called for DFP to draw up "standard guidance to NI departments on the timing and provision of relevant information to Assembly Statutory Committees." This guidance would require to be developed in consultation with the Assembly statutory committees and agreed by the Executive, with the commitment of individual Ministers being essential to ensuring its implementation. The Education Committee also proposed that "it would be for DFP in consultation with the Committee for Finance and Personnel (…co-ordinating the views of all Statutory Committees) to monitor Departments' adherence to the standard guidance."

30. The Assembly research recommended that consultation with the Assembly and its committees should be full and proper, with good practice suggesting a time frame of between two and four months. This would allow committees to fully scrutinise proposals and call for additional evidence, where necessary.

31. In its co-ordinated submission to the DFP review on behalf of all statutory committees in October 2008, the Committee recommended "that a budget process is established which maximises the opportunity for Assembly committees to provide early input" and favoured the inclusion of a stage similar to the position reports stage in the first mandate.[5] Despite this, in the recent mini-budget process which was undertaken to review spending plans for 2010-11, seven out of eleven statutory committees expressed dissatisfaction about the level of engagement with their departments. The Committee was strongly critical of the lack of proper engagement on departmental spending plans and considered that

"there is a need to establish firm protocols for the provision of timely and appropriate budgetary information to the statutory committees."[6]

32. Though strongly supportive of the DFP recommendation that "there should be early and more structured engagement between departments and Assembly Committees setting out the key issues and pressures facing NI Departments", the Committee considers that decisive measures are needed to put this into practice. Without wishing to be prescriptive on the information provided by departments to their respective Assembly committee, the Committee believes that there is a minimum standard that must be adhered to. In that respect, the Committee concurs with the recommendation from the Education Committee that DFP should take the lead in developing "standard guidance to NI departments on the timing and provision of relevant information to Assembly statutory committees" and that this should be agreed at Executive level, with departmental compliance being monitored by DFP in consultation with the Assembly statutory committees.

33. Also in respect of this DFP review recommendation, the Committee notes that the guidance on Budget 2010, which DFP issued recently to departments, states that "the unavoidable delays in initiating the Budget 2010 process means that there will be less scope to take this forward as part of the current process than will be the case in future years."[7] On this point, in noting that the timetable for the Executive's Budget 2010 process has an end date of "late December", the Committee calls on DFP to offer flexibility on this deadline to provide sufficient time for engagement with Assembly committees and the wider public. The Committee found that good practice would indicate a period of 2 – 4 months should be provided for in this regard. The Committee considers this feasible given that the Budget 2008-11 was not agreed in the Assembly until 29 January 2008 and, more recently, the Revised 2010-11 Spending Plans were not agreed by the Assembly until 20 April 2010.

|

(v) The DFP review recommended that: "There should be earlier engagement with key stakeholder groups by departments as part of the Budget process." |

34. As noted at paragraphs 18-19, respondents to the DFP review considered that the draft Budget was a fait accompli, and that the formal consultation period was therefore too late to significantly influence departmental spending proposals. Therefore, early engagement with key stakeholders was considered to be important. Respondents to the review criticised the level of engagement across departments, as not all departments consulted publicly on their plans.[8]

35. The committees for Education and Health both indicated that they were broadly supportive of this recommendation. The committees for Employment & Learning and the Environment considered that stakeholder participation is a key element in the preparation of budgets and was therefore to be welcomed and encouraged. The Committee for Regional Development agreed that stakeholder engagement should be encouraged on an ongoing basis; however, it sounded a note of caution that this would not obviate the need for meaningful consultation or consideration of equality implications of Budget and PfG proposals at either departmental or Executive level. The Committee for OFMDFM suggested that, if EQIAs were completed in advance of the draft Budget, this would lead to earlier engagement.

36. In addition to the criticism levelled at the lack of engagement between departments and their Assembly committees during the recent Review of 2010-11 Spending Plans, a number of submissions made to both DFP and the Finance Committee by stakeholders were critical of the level of public consultation in that process; for example, the Methodist Church in Ireland's Council on Social Responsibility[9] regarded the consultation as "at best flawed and at worst opaque. The process falls far short of good practice for consultations". It pointed to varying levels of information that were made publicly available, and questioned how stakeholders would be in a position to respond to a consultation when it was not clear what they were being consulted on. The submission recommended that consultation is conducted properly, with full details and guidelines being provided. In this regard, the Committee was also critical of the level of public consultation that had been undertaken in the Review of 2010-11 Spending Plans process. Indeed, the Committee did not become aware that DFP had issued a public consultation notice inviting responses on the Executive's proposals until after the process had concluded.

37. The Committee considers that greater influence can be brought to bear on spending plans at the earlier stages in the process, and therefore is supportive of the DFP recommendation that "there should be earlier engagement with key stakeholder groups by departments as part of the Budget process". However, the Committee believes that care should be taken by departments to ensure that a wide spectrum of stakeholder interests are included at this time to ensure that it is not the larger interest groups only that have the opportunity to influence the spending plans.

|

(vi) The DFP review recommended that: "DFP should take the lead role from the Strategic Investment Board (SIB) in developing capital investment allocations in the Budget process." |

38. The DFP review stated that "some stakeholders thought that there was too much confusion regarding the roles and responsibilities in respect of the capital allocations between SIB and DFP…In particular, with regard to the ongoing resource consequentials of the capital investment plans as well as consideration of the contextual issues within individual departments." As such, the Department proposed that, while SIB should retain focus on longer term investment plans, DFP should assume responsibility for capital as part of the overall Budget process.

39. The Committee found that there was no clear consensus on this issue from the views received from the other Assembly statutory committees. The Education Committee was supportive of the recommendation, while the Health Committee considered the current interaction between DFP, SIB, ISNI and DHSSPS to be confusing. The Employment and Learning Committee suggested that the recommendation should be examined more closely by the Finance Committee and the Committee for OFMDFM had no agreed view on the recommendation. The Committee for Regional Development urged caution in that there was a need to ensure that any limitations in terms of timeframes for spending reviews or budget cycles should not have a negative impact on a longer term strategy for capital investment.

40. A similar point was raised during the evidence session, when Departmental officials were asked if this recommendation would not result in the SIB merely becoming an implementation body, without consideration of strategic issues. In response, Departmental officials stated that they considered the opposite would be the case, and that the SIB would be better able to focus on more strategic elements. The Committee is mindful, however, that it has not had sight of the consultation responses provided to DFP on this issue, nor has it received the view of SIB on the matter. As such, at its meeting on 23 June 2010, the Committee agreed to take separate evidence from both DFP and SIB on the proposal in the autumn. Therefore, in noting the DFP proposal that it "should take the lead role from the Strategic Investment Board (SIB) in developing capital investment allocations in the Budget process", the Committee intends to take further evidence from the Department and also to invite separate evidence from SIB, to enable it to reach an informed position on this issue. There will also be a need to liaise further with the Committee for OFMDFM on the outcome of this work.

|

(vii) The DFP review recommended that: "Every departmental spending proposal should clearly state the impact on the respective PSA target, if successful." |

41. The DFP review considered that this measure would enable links to be made between spending proposals and outputs or outcomes. It was recognised, however, that some departmental expenditure may not be directly linked to PSA targets.

42. The Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety stated that much of its budget is spent by organisations other than the Department; future processes should therefore take cognisance of such links and structures. The committees for Education and OFMDFM were supportive of this recommendation. In its submission, the Committee for Regional Development contended that expenditure outwith PSA targets should be monitored to ensure achievement of stated outcomes, and that it should be included as part of the PSA monitoring process. Similarly, the Assembly research recommended that such spending should be presented alongside the Budget, as good practice would suggest.

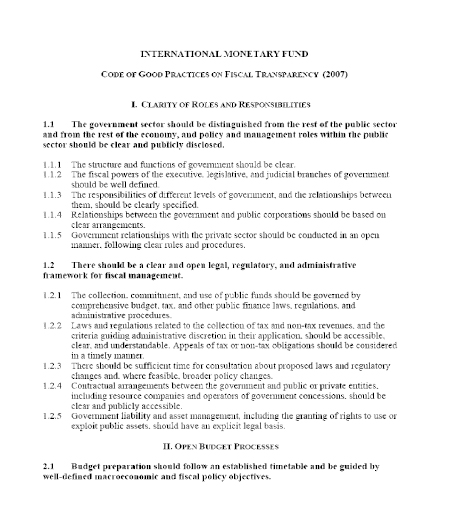

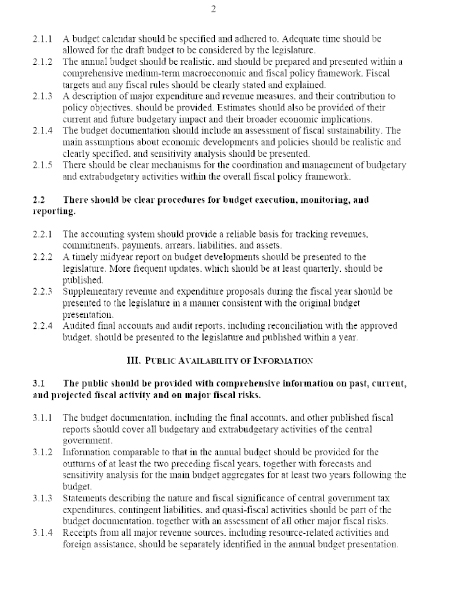

43. Arising from the Assembly research, the Committee notes that the IMF Code of Good Practices on Fiscal Transparency (2007) states that

"Results achieved relative to the objectives of major budget programs should be presented to the legislature annually."[10]

44. In reviewing the NI process against this Code, the Assembly research found that the PfG Delivery Report does not link PSA targets to individual departments, and stated that such an approach would be useful in enabling read across from the Delivery Report (i.e. outputs and outcomes) to the PfG and the Budget. It therefore recommended that "requests for resources should be disaggregated and justified." The Committee supports the DFP recommendation that "every departmental spending proposal should clearly state the impact on the respective PSA target, if successful." However, the Committee also believes that this linkage between spending and PSA targets at the bidding stage should extend to the reporting stage, whereby the End Year Delivery Reports would enable performance to be tracked at a departmental level in terms of inputs, outputs and outcomes.

|

(viii) The DFP review recommended that: "The Draft Budget document should include an easy to read summary at the start of the document." |

45. The DFP review found that a number of respondents considered that an "at a glance" summary should provide details of available resources, how they will be allocated and the anticipated outcomes. Public finance is a complex area, and the review concluded that such a summary should assist in making the Executive's proposals accessible to a wider audience.

46. This recommendation was supported by the committees for Education, the Environment, Health, OFMDFM and Regional Development. The Committee for Employment and Learning suggested that departments could be tempted to obscure information by the use of jargon and technical terminology, which "damages the process."

47. On a related issue, the Assembly research noted that information included in the Budget, in-year monitoring rounds and departmental accounts are provided on a resource basis whereas Estimates are presented on a cash basis, and stated that it is "all but impossible for anyone other than an expert in public sector accounting to reconcile the streams of information." This issue was also evident in the detailed comparison of the process in NI to the IMF's note on the Role of the Legislature in Budget Processes.[11] The Assembly research pointed to the reform process known as the Alignment (Clear Line of Sight) Project being undertaken by the Westminster Government, which aims to "simplify its financial reporting to Parliament by ensuring that it reports in a more consistent fashion, in line with the fiscal rules, at three stages in the process – on plans, Estimates and expenditure outturns."[12] The Assembly research suggested that such reforms could address a number of concerns in relation to the NI budget process, including: reconciliation of data across different publications; improving control of spending outside the estimates; the removal of confusing accounting practices and concepts; and the expansion of the Estimates to cover non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs). The research concluded that the financial information streams should be harmonised and aligned, to increase transparency and enhance the relationship between allocations and performance.

48. The Committee agrees with the DFP recommendation that "the Draft Budget document should include an easy to read summary at the start of the document." The Committee also agrees with the findings of the Assembly research in terms of the lack of transparency, and indeed confusion, resulting from the myriad of formats in which budget and financial information is presented. While recognising that this is complex by nature, the Committee further recommends that all relevant financial documents, including Budgets, Estimates and Resource Accounts, are simplified and harmonised to increase transparency and enhance the relationship between allocations and performance and also to ensure that they are more readily scrutinised by Assembly committees and accessible to the wider public.

|

(ix) The DFP review recommended that: "The full list of prioritised spending proposals submitted by departments as part of the draft Budget process should be published alongside the draft Budget document, including details of which proposals will be funded from the draft Budget allocations." |

49. The DFP review noted that during the Budget 2008-11 process confusion arose as to what was and was not being funded as a result of departments having significant flexibility "to distribute their draft Budget allocations between spending areas up until the final Budget position was agreed". This recommendation would therefore aim to address this shortcoming by providing greater clarity at the draft Budget stage.

50. In their responses to the Committee, a number of other statutory committees indicated broad support for this recommendation. The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure pointed out that it is difficult to determine departmental priorities when descriptors such as "inescapable" and "committed" are used to describe spending proposals. That Committee also expressed frustration with the lack of information on specific projects or programmes, with only high level figures having been provided in previous budget processes.

51. In light of the broad support amongst the other statutory committees, the Committee welcomes the DFP recommendation that "the full list of prioritised spending proposals submitted by departments as part of the draft Budget process should be published alongside the draft Budget document, including details of which proposals will be funded from the draft Budget allocations." The Committee notes that this aligns with the conclusion in its Report on the Executive's Draft Budget 2008-2011, published in December 2007, that "there would be benefit, in terms of transparency and scrutiny, from fuller and more standardised information on departments' bids and their outcomes being published as part of the draft Budget process."[13]

|

(x) The DFP review recommended that: "Departments should publish the High Level Impact Assessment for each spending proposal." |

52. The DFP review noted suggestions that equality considerations should, as a matter of course, be embedded within spending proposals and therefore any negative consequences would have already been considered. In addition, some considered that the impact assessments should be completed on PSAs rather than on bids, as allocations will be made against priorities. Nonetheless, the review considered that "it should be clearly stated which existing Equality Impact Assessment (EQIA) as well as other relevant impact assessment the proposal is linked to, and if not, when the respective programme EQIA or other relevant impact assessment will be completed."

53. As with the view expressed by the Committee for OFMDFM, the Committee supports the DFP recommendation that "Departments should publish the High Level Impact Assessment for each spending proposal." The Committee also recommends that departments should publish the results of the equality screening undertaken in respect of each spending proposal in fulfilment of the duties imposed by Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998.

|

(xi) The DFP review recommended that: "Supporting documentation including, for example, draft PSA and Efficiency Delivery Plans should be published as soon as possible after the draft Budget and PfG to provide a greater understanding of what will be achieved with the Budget allocations." |

54. While the DFP review recognised the importance of providing this supporting documentation as early as possible to enable effective scrutiny of spending proposals, it stated that there is "limited scope to provide supporting material until a later date". Following the evidence session with Departmental officials on 12 May, the Committee queried whether there is not a case for draft delivery plans accompanying the draft Budget and PfG to inform committee consideration and, in the case of efficiency delivery plans, provide some assurance regarding deliverability. Also, the Committee noted that respondents to the DFP review had identified "a lack of information provided on the efficiencies to be delivered by NI departments and how they would be achieved". In a written reply to the Committee's query, the Department explained that "in recognition of the quantum of work required of both DFP and departments in order to produce the draft Budget document, for practical reasons it was recommended that the publication of supporting documentation should be as soon as possible after the publication of the draft Budget document."

55. Responses from a number of other statutory committees indicated that any measures that would increase transparency were to be welcomed, and they were therefore supportive of this recommendation. However, the Regional Development Committee expressed a similar concern to this Committee in terms of why initial draft PSAs and EDPs could not accompany the draft Budget, particularly in view of the proposal to more closely link allocations to PSA targets. The Committee would reiterate the recommendation made in its submission to the DFP review that supporting documents, such as draft PSAs and draft delivery plans for efficiencies and investments, should be published alongside the draft Budget, as this would inform committee scrutiny and could provide some assurance regarding deliverability. Whilst recognising that such draft supporting documents may require development before being finalised, the Committee believes that, with careful planning and given the proposal to develop the PfG in advance of the Budget, it is reasonable to expect these draft documents to accompany the draft Budget.

|

(xii) The DFP review recommended that: "Assembly Committees should have the lead role in the consultation on the Executive's draft Budget proposals, with responses to the Executive co-ordinated by the Committee for Finance and Personnel." |

56. The DFP review noted that formal public consultation is not undertaken as part of the Welsh Budget process, although the public is able to respond to the draft Budget directly. Welsh Assembly committees undertake scrutiny of their respective department's budget allocations over a four week consultation period. Similarly, no formal public consultation is undertaken by the Scottish Executive, although again the public can respond directly on the draft Budget. The review considers that this approach should be followed for NI, whereby the Assembly committees would become the "key conduit for public responses to the Executive's draft Budget proposals."

57. The responses from most of the other statutory committees were not supportive of this recommendation. The Committee for Regional Development was of the view that committees would not have the authority to act on the outcome of the consultation and, as such, responsibility for consultation should rest with the Executive. The Committee for Education also did not consider this to be appropriate, while the committees for Enterprise, Trade and Investment and Culture, Arts and Leisure noted that they do not take the lead role in consulting on any other departmental policies. The Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety sounded a note of caution with regard to the lack of committee resources to undertake such a consultation.

58. The Committee recognises that all Assembly committees will, in fulfilling their scrutiny role, wish to consult with key stakeholders with regard to departmental spending proposals. However, members noted during the evidence session with Departmental officials on 12 May 2010 that Assembly committees, as currently constituted, may not have the time, resources, specialist knowledge or ability to do anything other than to act as a conduit for information passed to them by the public or various groups.

59. The Committee does not support the DFP recommendation that "Assembly Committees should have the lead role in the consultation on the Executive's draft Budget proposals, with responses to the Executive co-ordinated by the Committee for Finance and Personnel." In noting that other statutory committees have also voiced concern with this proposal, the Committee believes that this would be an inappropriate role for Assembly committees to fulfil, especially given that they would not have the authority to act on the outcome of such consultation.

|

(xiii) The DFP review recommended that: "In responding to the draft Budget, any proposal to increase spending on a particular service by a Committee should be accompanied by an equally detailed proposal as to how this could be funded." |

60. The review notes that, in Scotland, any alternative spending proposals by committees are costed, and details of how the costs will be provided for are also included. The Finance Committee in the Scottish Parliament examines the overall Budget position and allocations. The review considered the process in Scotland to be more developed than in NI, and it was noted that there "appears to be more of an overall collective purpose with portfolios or departments working together towards the same aim, which has resulted in more cross departmental working."

61. The review also pointed to the process in Wales, whereby Assembly committees can only put forward alternative spending proposals within the total resource available. To keep within the resources available to the NI Executive, it was proposed that the implications that funding alternative proposals will have on other services should be clearly set out. Furthermore, the DFP review also suggested that "the Committee for Finance and Personnel, in responding on behalf of all the Committees, should identify whether it views the funding proposal to be realistic or not."

62. The Committee for the Environment advised that it is aware of funding constraints faced by that Department, and therefore avoids putting forward unrealistic spending proposals or reductions. The Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety indicated that it was broadly supportive of this recommendation; however this view was not widely shared among other statutory committees. The Committee for Education considered that it does not have the necessary resources to undertake detailed costings and funding arrangements for any alternative spending proposals it puts forward; furthermore, it did not have access to the necessary information from its Department to support this. The Regional Development Committee rejected this recommendation "on the grounds that it would not be practical or achievable without full disclosure of information from departments and the Executive, in a regular, timely, transparent and accessible manner." The considerations in respect of resources, in terms of specialist support on public finance, and access to information are discussed later in the report.

63. Finally, while welcoming the focus afforded to committees by DFP in this review, the Committee for Employment and Learning stressed that each committee should be free to scrutinise its own Department, and the Committee for Finance and Personnel should have the role of co-ordinator and not arbiter of the process. Similarly, the Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure stated that it is not convinced that it is appropriate for the Finance Committee to arbitrate on proposals from other statutory committees. On this point, the Finance and Personnel Committee considers that a conflict of interest could arise if it were to assess alternative spending proposals put forward by other statutory committees in respect of their departments, while it also has a responsibility for assessing the departmental plans for DFP.

64. In its consideration of this issue, the Committee commissioned research on the potential for the Assembly to establish a central budget committee in the future (Appendix 5). The Assembly research paper noted that budgets are dealt with by legislatures in the following three ways:

(i) centralised, where a budget committee is assigned full responsibility for budget issues;

(ii) dispersed, where responsibility is divided amongst sectoral committees; and

(iii) a hybrid model, whereby portions of the budget are considered by sectoral committees and action is recommended within a framework set by a centralised budget committee.

The current system in NI is dispersed, with the Finance and Personnel Committee performing a co-ordinating role; examples of centralised and hybrid models in other jurisdictions were also examined.

65. The research paper cites a number of issues that would need to be considered more fully, including the need to:

- decide whether to move forward with a centralised or hybrid model, or retain the status quo;

- explore whether a budget committee's remit could be expanded to include monitoring of cross-cutting issues, including the delivery of PfG and PSA targets;

- examine if existing legislative provision allows for a budget committee to be established, or whether an amendment to legislation is required; and

- consider the potential membership of a budget committee and if there would be the possibility for a conflict of interest where a Member might sit on both it and a statutory committee.

In addition, the research paper points out that committee procedures and structures are linked to the overall budget process, which is likely to be subject to a degree of reform moving forward. Therefore, consideration should be given as to whether the committee structure should be redesigned in parallel with budgetary reforms, or if it would be more appropriate to wait for a firm budget process to be established and then design the structures accordingly.

66. The Committee notes with interest the recommendations from DFP that "in responding to the draft Budget, any proposal to increase spending on a particular service by a Committee should be accompanied by an equally detailed proposal as to how this could be funded"; and that "the Committee for Finance and Personnel, in responding on behalf of all the Committees, should identify whether it views the funding proposal to be realistic or not." The Committee, however, sees such an approach as more applicable in the context of a reformed system of Assembly financial scrutiny; whereby departmental committees would have access both to the necessary financial information held by departments and to additional specialist support and where a central budget committee existed with the requisite powers. The Committee believes that such a scrutiny model warrants more detailed consideration by the Assembly in the future.

|

(xiv) The DFP review recommended that: "The Final Budget Statement and debate should be combined with the Main Estimates process." |

67. The DFP review considered that the current process for agreeing and debating the Budget and Main Estimates encourages "significant amounts of repetition, duplication and confusion." The recommendation is to follow the approach in Scotland, whereby both are taken forward simultaneously. Following the evidence session with Departmental officials on 12 May, the Committee sought clarification on how this proposed approach would work in practice. In follow up correspondence, DFP explained that:

"…rather than voting on the revised Budget in December or January, the Vote on Account in February and the Main Estimates in June, this process would mean that the revised Budget and Main Estimates and Budget Bill are combined in December or January, negating the need for a Vote on Account."[14]

68. The Department did, however, recognise that a detailed review would be needed to consider the practical implications of these changes to the financial processes and that this review would include consultation with the Assembly statutory committees and with the Comptroller and Auditor General.

69. The committees for Education, Health, OFMDFM and Employment & Learning were supportive of this recommendation. On the other hand, while it considered there is a need to streamline the process, the Regional Development Committee stated that it was not in a position to support this recommendation in the absence of detail regarding the future budget process. It also stressed that streamlining the process should not unwittingly result in it becoming less transparent or providing less opportunity for debate in plenary.

70. Related to the issue of streamlining the process, reference has been made previously to the Assembly research findings with regard to the different formats used to present information on the Budget and the Estimates, and the need for this supporting information to be simplified and aligned.

71. During the evidence session with Departmental officials, the Committee heard that the merging of these stages should increase the time available for scrutiny by committees, as it would no longer be necessary to consider the issues either separately or in parallel. The Committee is, in principle, supportive of the DFP recommendation that "the Final Budget Statement and debate should be combined with the Main Estimates process" as this should make for a more streamlined and harmonised approach. That said, the Committee looks forward to being consulted on the detail of this proposal and firmly believes that such change should only be made in the context of a settled future budget process, which will require to be agreed between the Executive and the Assembly.

Action Plan for Implementing the DFP Recommendations

72. During the evidence session on 12 May 2010, DFP officials undertook to provide the Committee with a copy of the action plan for the implementation of the recommendations included in the Review report. Whilst it was requested that this be provided in advance of the Committee's meeting on 19 May, the Department subsequently advised that it could not be made available until it received Executive clearance and this had not taken place by the time the Committee agreed this Inquiry report on 30 June. As such, the Committee looks forward to receiving the action plan for implementing the DFP review recommendations and expects that this will be updated to take account of this co-ordinated response on behalf of the Assembly statutory committees.

Other Issues and Next Steps

Cross-departmental working

73. A number of key points that were raised in the DFP review report were not directly addressed in the recommendations. In particular, stakeholders noted the competition for Budget allocations among departments, which made cross-departmental working difficult. It was also perceived that cross cutting issues were often afforded only low priority. It was suggested that the agreement of the PfG in advance of the Budget may assist in this regard as departments would be better able to take direction from priorities which had been set. It was further suggested that OFMDFM would be "the most suitable part of the Executive to facilitate cross departmental working and joint bidding".

74. In terms of the Committee's previous consideration of this issue, in 2007, as part of its examination of the Executive's Draft Budget 2008-2011, the Committee raised a number of concerns with DFP regarding the discontinuation of discrete cross-cutting funds, which had previously existed in the form of the Priority Funding Packages and the Executive Programme Funds. The Department made a number of points in response, including that: the creation of the such funds required departmental budgets to be "top sliced", which reduced resources available for the generality of pressures across departments; the pattern of underspend in these ringfenced funds had been considerably higher than the average; and the cross-cutting dimension would be dealt with through the Executive's PSAs. Nonetheless, in its Report on the Executive's Draft Budget 2008-2011[15], the Committee sought assurance that these important spending areas, such as Children & Young People, would not lose priority and that any new funding arrangements do not hinder access by the voluntary and community sector. The Committee continues to place high importance on cross-departmental working, not only in terms of policy and service delivery but also in the context of improved efficiency and effectiveness across the public sector. As such, the Committee believes that the Executive must bring forward proposals for improving the arrangements both for promoting and funding collaborative working by departments and other public bodies and for measuring and monitor performance in this area.

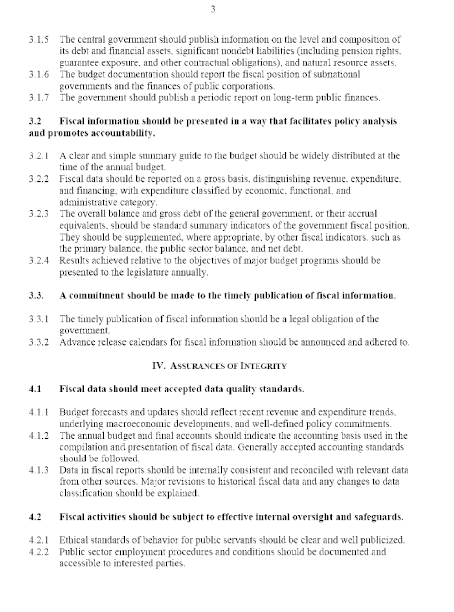

Independent Budget and Financial Scrutiny

75. The Committee noted from the Assembly research that the IMF's Code of Good Practices on Fiscal Transparency (2007) states that, in respect of assurances on integrity, fiscal information should be externally scrutinised.[16] It advises that "independent experts should be invited to assess fiscal forecasts, the macroeconomic forecasts on which they are based, and their underlying assumptions". In comparing the NI budget process against good practice, the Assembly research noted that no verification or scrutiny is undertaken by independent experts on the Executive's budget proposals or the financial information and assumptions underpinning the proposals. The research suggested that the independent analysis could be provided by consulting an independent fiscal agency, or by passing responsibility for fiscal projections and assumptions to a fiscal council, as is the case in the Netherlands, Austria and Belgium; though it was recognised that the cost of funding such a fiscal council may be prohibitive.

76. The Assembly research also suggested that the Executive should publish an assessment of the fiscal picture. In contrast to what good practice would advise, there was no comprehensive assessment of fiscal sustainability in the 2008-11 Budget or the recent Review of 2010-11 Spending Plans. The Executive does publish a Net Fiscal Balance report co-ordinating all revenue statistics, which highlights the large fiscal deficit in NI. However, the Assembly research pointed out that this is not published alongside the Budget and does not provide an assessment of the sustainability of proposals or programmes. The Assembly research suggested that:

"the Executive should produce – as far as it is possible to do so in the context of how Northern Ireland is funded – an assessment of the fiscal sustainability of its policies including:

- A statement of fiscal risks.

- Some form of medium-term fiscal plan.

- A regular assessment of demographic change and its potential impact."[17]

77. Whilst recognising that the Executive does not have full fiscal control and therefore direct comparisons with arrangements in other jurisdictions are difficult, the Committee considers that it would be good practice both for the Executive's draft Budget to be accompanied by some level of assessment of the fiscal sustainability of the associated policies and for some form of independent external scrutiny to be applied to the Executive's spending proposals. On this latter issue, as part of its Stage 2 Inquiry report, the Committee will be examining the potential for elements of this independent external scrutiny function to be exercised cost-effectively through the reconfiguration and greater use of the existing options for specialist support to Assembly committees and Members in undertaking financial scrutiny.

Access to Information

78. The importance of committees having access to appropriate and timely information on departmental budgets and expenditure has been alluded to already in this report. The Committee considers that the implementation of some of the aforementioned recommendations will assist in this regard and help to address an important determinant to improving the Assembly's financial scrutiny. That said, the Committee believes that additional provisions are likely to be required. As part of the evidence received for Stage 2 of the Inquiry, the Committee has heard that the pilot period that successfully established a Public Finance Scrutiny Unit in the Scottish Parliament enabled information access via a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the Parliament and the Executive. Included in the options which the Committee intends to explore as part of Stage 2 of the Inquiry are:

(i) The Assembly agreeing a MoU with the Executive to facilitate information flows.

(ii) Enabling information flow through regulation (e.g. additions to the Assembly's Standing Orders); and

(iii) Enabling information flow through primary legislation.

Stage 2 of the Inquiry: Resources

79. Given the planned publication of a draft Budget in autumn 2010[18], the Committee agreed to proceed with Stage 2 of its Inquiry "to review the resources available for assisting Assembly statutory committees and members in undertaking budget and financial scrutiny and to put forward a set of practical recommendations for enhancing the capacity of the Assembly in this regard" in parallel with Part 2 of Stage 1. The Committee expects to publish the report on Stage 2 of its inquiry shortly after summer recess.

Stage 3 of the Inquiry: Review of Monitoring Rounds

80. Stage 3 of the Budget Scrutiny Inquiry aimed to "review the processes for the in-year monitoring of departmental expenditure by the Assembly and its statutory committees, with a view to making recommendations to further improve the operation of the processes and to facilitate more effective scrutiny". However, subsequent to the Terms of Reference for this inquiry being agreed by the Committee in July 2008, DFP decided to undertake its own review of the in-year monitoring process. The Committee took evidence from DFP officials on 20 January 2010 on the outcome of this review, which was completed in late 2009. The DFP report, Review of the NI Executive In Year Monitoring Process, and the Official Report of the evidence session are provided at Appendix 3 and Appendix 2 respectively.