Report on the Climate Change Bill

Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

Session: Session currently unavailable

Date: 08 December 2021

Reference: NIA 118/17-22

AERA Committee Report on the Climate Change Bill.pdf (1.11 mb)

Download a PDF version of this report (PDF, 88 pages, 1.1MB)

Read a Summary Bill Report that highlights the key points of the full report

This report is the property of the Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs.

Neither the report nor its contents should be disclosed to any person unless such disclosure is authorised by the Committee.

Ordered by the Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs to be printed on 8 December 2021.

Report Number: NIA 118/17-22

Mandate 2017-22

Table of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Name |

|---|---|

|

AERA |

Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs |

|

AFBI |

Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute |

|

BITC |

Business in the Community |

|

CAP |

Climate Action Plan |

|

CCC |

United Kingdom Committee on Climate Change |

|

CIWM |

Charted Institute of Wastes Management |

|

DAERA |

Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs |

|

EJNI |

Environmental Justice Network Ireland |

|

EU |

European Union |

|

GB |

Great Britain |

|

GHG |

Greenhouse Gas |

|

IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

|

KNIB |

Keep Northern Ireland Beautiful |

|

LULUCF |

Land-Use, Land-Use-Change and Forestry |

|

NI |

Northern Ireland |

|

NIEL |

Northern Ireland Environment Link |

|

NIMEA |

Northern Ireland Meat Exporters Association |

|

ROI |

Republic of Ireland |

|

SAMBIT |

Small and Micro Business Impact Test |

|

TEO |

The Executive Office |

|

UCD |

University College Dublin |

|

UFU |

Ulster Farmers’ Union |

|

UK |

United Kingdom |

|

UKCCSRC |

United Kingdom Carbon Capture and Storage Research Centre |

|

UN |

United Nations |

|

NO2 |

Nitrogen Dioxide |

|

MTCO2e |

Metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent |

Contents

- Powers and Membership

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Background and Context

- Current Status: UK CCC’s Progress Report June 2021

- NI Greenhouse Gas Emissions Profile

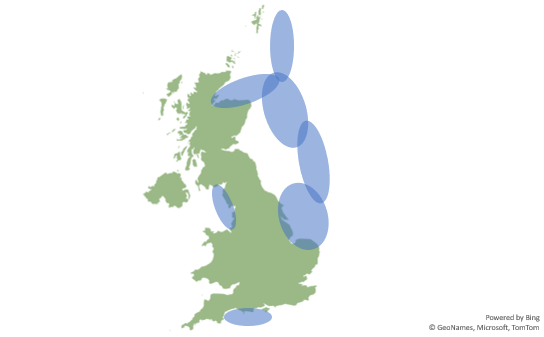

- CCC Advice on NI Climate Change Mitigation

- Climate Change (No.1) Bill

- Committee’s Consideration of the Bill

- Clause-by-Clause Consideration

- Recommendations

- References

- Appendices

1. Powers and Membership

1. The Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of Strand One of the Belfast Agreement 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 48.

2. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs and has a role in the initiation of legislation.

3. The Committee has power to:

- consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- consider subordinate legislation and take the Committee Stage of primary legislation;

- call for persons and papers;

- initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

4. The Committee has nine members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, and a quorum of five. The membership of the Committee is:

Mr Declan McAleer MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Philip McGuigan MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Ms Clare Bailey MLA

Mrs Rosemary Barton MLA

Mr John Blair MLA

Mr Maurice Bradley MLA (to 21 September 2021) and Mr Tom Buchanan (from 1 November 2021)

Mr Harry Harvey MLA

Mr William Irwin MLA

Mr Patsy McGlone MLA

2. Executive Summary

5. Climate Change is one of the most important issues facing modern society and countries across the world have enacted laws in recent years to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to mitigate the damage caused to the environment by global warming.

6. Northern Ireland is unique among jurisdictions of the United Kingdom in that it does not presently have Climate Change legislation in place setting out emissions targets and a framework for meeting these. The Republic of Ireland has recently updated its climate law and in July 2021 the European Union set out legislative commitments on climate action to be introduced across the bloc.

7. This report presents the work of the Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs in scrutinising the Climate Change Bill that was introduced in March 2021 and seeks to establish local Climate Change legislation for Northern Ireland.

8. Between May and September 2021 the Committee undertook an extensive call-for-evidence exercise and engaged with a wide range of stakeholders representing organisations across various sectors of the economy to help inform its considerations on the Bill’s provisions, and its potential consequences.

9. Through its deliberations in the Autumn the Committee sought a number of areas of amendment in order to strengthen the Bill and reflect the views of stakeholders to ensure that it constitutes an effective framework to facilitate Climate Change mitigation in Northern Ireland.

10. The Committee recognises how important an issue Climate Change is for local people and businesses and that there is a strong desire for urgent action to address the problems caused to the environment. However, it is acknowledged that significant behavioural and economic change will be required to reduce our emissions and this will have a profound impact on some sectors of our economy, as well as for households and how we go about our daily lives.

11. The Committee welcomes the introduction of local Climate Change legislation and is in agreement with most of the provisions of the Bill and recommends that it proceed to the next stage of the legislative process in the Assembly.

12. A summary of the Committee’s considerations is as follows:

- The Bill’s overarching target of delivering net-zero emissions by 2045 is highly ambitious and goes beyond what is currently recommended as achievable by the UK Committee on Climate Change

- There is significant concern about the potential impacts pursuit of this target could have on the local agri-food sector in particular

- Given the contention around the proposed emissions target, the Committee did not come to an agreed position on this aspect of the Bill

- The Bill’s pathway to reduce emissions through Climate Action Plans was well-received by stakeholders and the Committee considers that this will be an effective mechanism to ensure that there is cross-sectoral engagement on policies and plans that will be put in place in the future

- The establishment of a Climate Commissioner is supported as a means of providing locally-based, independent scrutiny and oversight of government action. The Committee has however, recommended amendments to implement safeguards with regards the Commissioner’s powers to access documents

- - Given the need to support sectors of the local economy in the move to lower emissions, the Committee has recommended stronger Just Transition principles in the Bill and establishment of a Just Transition Fund for Agriculture

- It is recognised that Climate Change mitigation measures will incur a significant financial cost and undoubtedly will require investment from public monies. However, it is difficult to project the entirety of the resource requirement accurately given uncertainties about the emergence of new technologies, methods of financing and any future provision of Climate Change funding from the UK Government to Northern Ireland.

3. Introduction

13. This report outlines the work undertaken by the Assembly’s Committee for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (AERA) to scrutinise the Climate Change Bill that passed Second Stage in May 2021, and the Committee’s recommendations to support Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) in their consideration of the Bill.

14. For the purposes of this report the Bill is referred to as the Climate Change (No.1) Bill in order to distinguish it from a separate piece of legislation pertaining to this policy area that was referred to the Committee for scrutiny in September 2021.

15. It provides an overview of:

- Contextual information relating to Climate Change and its effects globally, nationally and locally

- Legislative approaches to address Climate Change at multi-national, national and regional level

- The current status of Climate Change mitigation in the UK as reported by the Committee on Climate Change (CCC)

- A breakdown of the current greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions profile in Northern Ireland (NI)

- A summary of the advice provided by the CCC in terms of expectations for NI in relation to reducing emissions

- A synopsis of the salient aspects of the Bill

- The call-for-evidence activities undertaken by the Committee

- The Committee’s deliberations and areas where amendments have been sought

- Clause-by-clause consideration

- Recommendations made to facilitate wider policy development

4. Background and Context

Climate Change

16. Climate Change is an umbrella term used to describe transformations in the environment that are unrelated to natural variations in weather patterns and ecosystems.

17. While some individuals and organisations challenge the concept of Climate Change and others claim that its effects are overstated, it is widely accepted that human activity has had a profound impact on the environment and that this has compounded in recent decades.

18. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) August 2021 report Climate Change: The Physical Science Basis states that “it is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land.”

19. Climate Change has occurred as a direct result of “global warming”, i.e., the earth’s temperature has risen.

20. There is extensive evidence that demonstrates that this has been caused by the emission of gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and methane (CH4) into the atmosphere that remain near the earth’s surface and prevent sunlight and heat from escaping, thus causing a “greenhouse” warming effect across the globe – they are therefore referred to as “greenhouse gases” (GHGs).

21. Global warming has had a number of profound impacts, particularly the melting of the polar ice caps, subsequently leading to a rise in global sea levels. This ecological destabilisation has disrupted normal weather patterns and increased the prevalence of events such as floods, storms and fires that are becoming more intense and prolonged, along with significant changes in temperatures that are increasingly extreme and erratic:

“Every additional 0.5°C of global warming causes clearly discernible increases in the intensity and frequency of hot extremes, including heatwaves and heavy precipitation as well as agricultural and ecological droughts in some regions” IPCC (2021)

22. It also affects ecosystems, endangering natural habitats for flora and fauna, and air quality with contaminate particulate matter circulating in areas of high-population density and concentration of industry.

23. While the gases that contribute to global warming occur naturally, the overwhelming bulk of harmful GHGs released into the atmosphere emanate directly from human consumption, behaviour and industry.

24. Particularly, the use of fossil fuels (oil, gas, coal etc), which are the primary source of CO2, is a key contributor to global warming. Society relies on fossil fuels as its predominant energy source and they facilitate a wide range of activities including:

- Travel – oil and petrol are used as fuel for cars, trains and buses

- Domestic heating systems

- Manufacturing of products, clothes, and other items that are consumed by purchasers

- Shipping and aviation for personal travel or transit of goods across the globe

- Construction of buildings and other infrastructure

- Food production

- Electricity generation

25. As a result, intensified global warming has occurred over the last 150 years since the start of the industrial revolution when these fuels were first used to power new technologies and the means of mass production. It is estimated that human intervention has contributed to a rise in world temperature of at least 1.07°Cfrom 1850-1900 compared to 2010-2019.

26. However, its effects on the environment have accelerated, and have been more clearly evident, in recent decades due to the fact that GHGs linger in the atmosphere causing a cumulative warming effect, thereby compounding the disruptive impact on weather systems.

27. The IPCC has found that global surface temperature has grown at a faster rate since 1970 than in any other 50-year period over the past 2,000 years.

28. Climate Change is a global problem as GHGs cannot be attributed to any particular nation or region of the world. There is an obligation both on developed economies, which retain a historical responsibility for industrialisation, and on developing economies that are advancing their productive and technological capabilities, to address it.

Impact of Climate Change Globally

29. As highlighted above global warming has contributed to the occurrence of ecological disasters and extreme weather events that are increasingly common. Some of the most high-profile examples in the past number of years are shown below:

Figure 1 - Flooding in Germany and Belgium in 2021

“The floods and destruction are unimaginable. We cannot even assess the scale of the damage yet.” - Mayor of North-Rhine Westphalia

Figure 2 - Australian bushfires 2020

“There are a number of fires that are coming together - very strong, very large, intense fires that are creating some of these fire-generated thunderstorms” - New South Wales Rural Fire Service Commissioner

Figure 3 - Locust swarms in east Africa in 2020

“It is the locusts that everyone is talking about. Once they land in your garden they do total destruction. Some people will even tell you that the locusts are more destructive than the coronavirus.” - Ugandan Farmer

30. It is impossible to quantify accurately the colossal societal and human cost of such events, but they do cause widespread destruction and loss of life. A 2021 study projected that just under 500,000 people living in the global south had died as a result of climate disasters since 2001, which is likely to be a significant underestimate.

31. Further, the economic cost to governments to support communities in the immediate aftermath of climate disasters, and to recover in the long-term, is immense and stark. The World Meteorological Organization estimates that the Top-10 most costly weather events recorded between 1970 and 2019 accounted for approximately $521 billion in economic losses. In Europe alone, there were 1,642 reported disasters during this time period, resulting in 160,000 deaths and $476.5 billion in economic damages.

Impact of Climate Change Nationally

32. The consequences of Climate Change are also evident in the United Kingdom (UK), with a higher number of floods, intense storms and cold snaps recorded since 2000 compared to previous decades.

33. The Met Office July 2021 report on the status of the UK’s climate highlights some of the changes seen in the country’s weather system in recent years:

- All of the Top-10 warmest ever recorded calendar years have occurred since 2002

- The hottest ever temperature was recorded in 2019 in Cambridgeshire– 38.7°C

- Winters and Summers between 2009 and 2018 were on average 12% and 13% wetter respectively than between 1961 and 1990

- The mean sea level in the UK has risen by approximately 17cm since the start of the 20th Century

Impact of Climate Change Locally

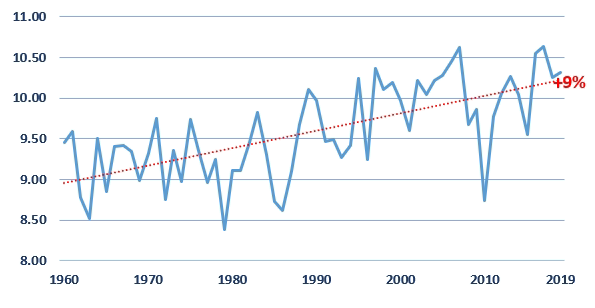

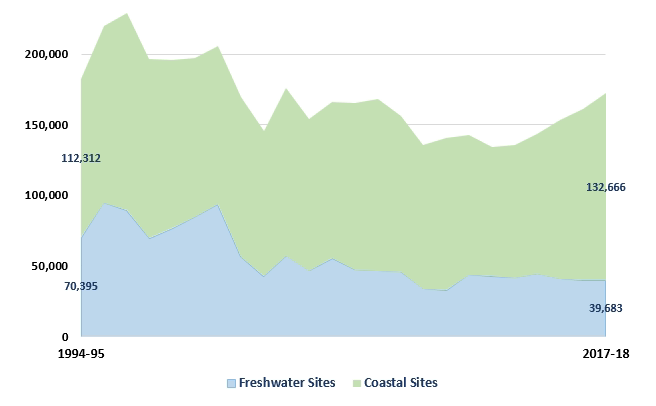

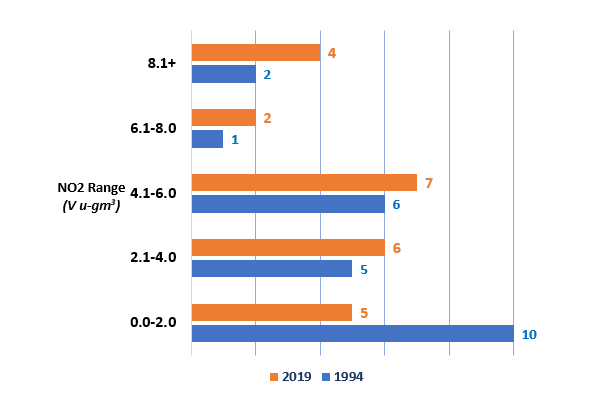

34. The below charts provide an indication of how Climate Change has affected the environment and ecosystem in NI, highlighting that:

- There has been a rise in the mean average annual temperature since 1960

- The number of “warm” days recorded in NI each year (days with a minimum temperature of >20°C) has increased over the last five decades with a decline in the number of recorded “frost” days per annum (<0°C)

- There has been a significant decline in the wetland bird population at freshwater sites over the past two decades

- In some areas of NI, the air quality in terms of monthly NO2 levels has worsened since the mid-1990s

Northern Ireland Annual Minimum Temperature (°C)

Average Number of Annual Frost and Warm Days by Decade

| Decade | Number of Frost Days Per Year (<0°C) | Number of Warm Days Per Year (>20°C) |

|---|---|---|

|

1970-1979 |

44 |

33 |

|

1980-1989 |

44 |

36 |

|

1990-1999 |

29 |

30 |

|

2000-2009 |

37 |

39 |

|

2010-2019 |

37 |

42 |

Northern Ireland Wetland Bird Population Trend 1994-95 to 2017-18

Monthly NO2 Reading Range at Lough Navar and Hillsborough 1994 and 2019

Paris Agreement (2015) and International Approaches to Mitigate Climate Change

35. Over the past 15 years there has been a concerted effort by governments across the globe to engage multilaterally to advance initiatives to mitigate the effects of Climate Change, as it cannot be effectively tackled by countries working in isolation.

36. The 2015 Paris Agreement marked an important milestone where 196 nations pledged to:

“Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of Climate Change”

37. The signatories to the Agreement included leaders from countries across the world, including 55 parties of the United Nations (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change that account for 55% of global emissions.

38. The Paris Agreement established a political consensus to encourage countries to reduce GHGs in order to reverse global warming and precipitated the introduction of legislation by individual nations setting out how they would achieve this.

39. The IPCC reported on the effectiveness of global mitigation strategies in August 2021 and determined that, based on a range of modelling analyses, it is more likely than not that global warming will exceed 1.5 °C by the middle of the century and that deep, and extensive, CO2 removal via engineered technology is required, along with attainment of net-zero emissions, to stabilise global warming.

40. An international stocktake of progress will take place in 2023 in order to assess what further action governments may need to take to deliver on the Paris Agreement.

41. In November 2021 the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 26) was held in Glasgow with the overarching goal of intensifying international support to address Climate Change.

42. A number of multi-lateral agreements spanning various aspects of mitigation and adaptation were made at COP26 including:

- A pledge to end and reverse deforestation by 2030

- The United States and European Union agreed to cut methane emissions by 2030

- Forty countries committed to reducing coal consumption as a primary energy source

- The United States and China agreed to work together throughout the 2020s to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 °C

- - The Glasgow Climate Pact which places a number of obligations on signatories, including:

- An international agreement to “phase down” the use of coal

- A pledge to cut international GHG emissions by 41.9 gigatons by 2030

- A request to adopt more ambitious targets: “[Parties must] revisit and strengthen the 2030 targets in their nationally determined contributions as necessary to align with the Paris Agreement temperature goal by the end of 2022.”

- Increase support to developing countries by mobilising $500bn of finance for mitigation and adaptation by 2025

National Approach to Mitigate Climate Change

43. In 2008 the UK Government passed the Climate Change Act, a seminal piece of legislation which set out a framework for how the constituent jurisdictions of the UK should work towards reducing the harmful effects of Climate Change by lowering GHG emissions.

44. The core elements of the Act included:

- A long-term statutory target for the UK to reduce its GHG emissions by 80% by 2050 (compared to 1990 levels). This target was subsequently revised in 2019 to legislate that the UK should reach net-zero GHG emissions by 2050

- A system of carbon budgeting, where prescriptive emission levels for the country are set on a 5-yearly basis

- The establishment of the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) comprising scientific experts to provide independent advice to the government on the UK’s Climate Change policy and progress

The CCC has subsequently established itself as a highly-respected, world-leading authority and provides advice to organisations and countries across the globe - Imposition of the National Adaptation Programme (NAP) that requires the government to publish every 5 years the policies that it intends to introduce to manage the effects of unavoidable Climate Change

45. Since 2019 the Conservative government has made a number of high-profile policy announcements as part of its overarching drive to meet the net-zero target, including:

- Ending direct government support for the fossil fuel energy sector overseas

- Ending the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030

- Spending at least £3 billion of climate finance on nature-based solutions

- Climate-related disclosures will be mandatory by the year 2025

- Ambition to create 2 million green-based jobs across the UK by 2030

46. Whilst the Climate Change Act 2008 applies to all regions of the UK in terms of meeting the net-zero target, both the Welsh and Scottish governments have developed independent legislative pathways to mitigate GHG emissions in their respective localities:

- In 2016 the Welsh Assembly passed the Environment (Wales) Act which introduced a duty on the government to set carbon budgets specifically for Wales. This has been followed by subsequent regulations setting GHG emissions targets as follows:

- By 2030 emissions will be 63% lower than 1990 levels

- By 2040 emissions will be 89% lower than 1990 levels

- By 2050 emissions will be net-zero compared to 1990 levels

- The Scottish government passed the Climate Change (Scotland) Act in 2009 that aimed to be more ambitious than the 2008 Act and the emissions target has been revised to deliver net-zero GHG emissions by 2045. Under the Act, Scottish Government Ministers are required to produce annual targets in order to help monitor progress in terms of emissions

47. In the Republic of Ireland (ROI), legislative progress was first established via the Climate Action and Low Carbon Development Act (2015). This legislation, whilst not setting binding GHG emissions targets, established a framework to support ROI to transition to a carbon neutral economy through creation of an independent Advisory Council and placing a responsibility on the government to produce a National Mitigation Plan for emissions reduction and a National Adaptation Framework.

48. In July 2021 the Climate Action and Low Carbon Development (Amendment) Act 2021 was passed. This amended the 2015 Act in order to:

- Commit the Irish Government to moving “to a climate resilient and climate neutral economy by the end of 2050”

- Establish a system of Carbon Budgeting

- Place a responsibility on local authorities to produce Climate Change Action Plans every 5 years

49. There is presently no specific Climate Change legislation in NI. However, as part of the 2020 New Decade, New Approach agreement, the NI Executive made a commitment to bring forward a Climate Change Act to give environmental targets a strong legal underpinning, as well as developing a new Energy Strategy and reviewing policies in light of the Paris Agreement.

5. Current Status: UK CCC’s Progress Report June 2021

50. As part of its responsibilities under the Climate Change Act 2008, the CCC reports periodically to the UK Government on its progress in terms of meeting its obligations on mitigation, adaptation and reducing GHG emissions.

51. In its most recent report in June 2021 the CCC outlined that the UK has made significant advancements: GHG emissions are 50% lower compared to 1990 and certain sectors of the economy including electricity supply, waste management and manufacturing have enacted substantive changes to their operating models to reduce their carbon effect.

52. However, the report highlighted that the UK still faces significant challenges and that “we continue to blunder into high-carbon choices”, noting that some industries such as transport, shipping, aviation and agriculture are yet to implement changes to the extent and intensity required to reach net-zero by 2050.

53. The CCC acknowledged the ambitious pledges made by the Conservative Government since 2019 with regards mitigation policies, but cautioned that these statements of intent need to be delivered via credible, well-thought-out policies supported by targets, appropriate funding and plans for job transition.

54. The report warned that if the UK government, and other nations, failed to act on their ambition in this “decisive decade”, it will be impossible to meet the Paris Agreement and more robust, extensive and possibly disruptive action will have to be taken in the future to avoid further climate damage.

55. The CCC identified Seven Priority Areas for the UK Government to focus on in order to ensure it has the best opportunity possible to meet the net-zero 2050 target:

| Priority Area | Priority |

|---|---|

|

1 |

Delivery of the 2030 transition to electric vehicles |

|

2 |

Accelerating decarbonisation of building construction |

|

3 |

Land-Use Change through extensive reforestation and peatland restoration along with delivery of low-carbon farming practices |

|

4 |

Decarbonisation of manufacturing through incentive mechanisms that support fuel switching and implementation of carbon-capture technologies |

|

5 |

Low-carbon power generation |

|

6 |

Development and implementation of a Hydrogen Strategy as an alternative power source |

|

7 |

Investment in domestic-engineered GHG removal |

6. NI Greenhouse Gas Emissions Profile

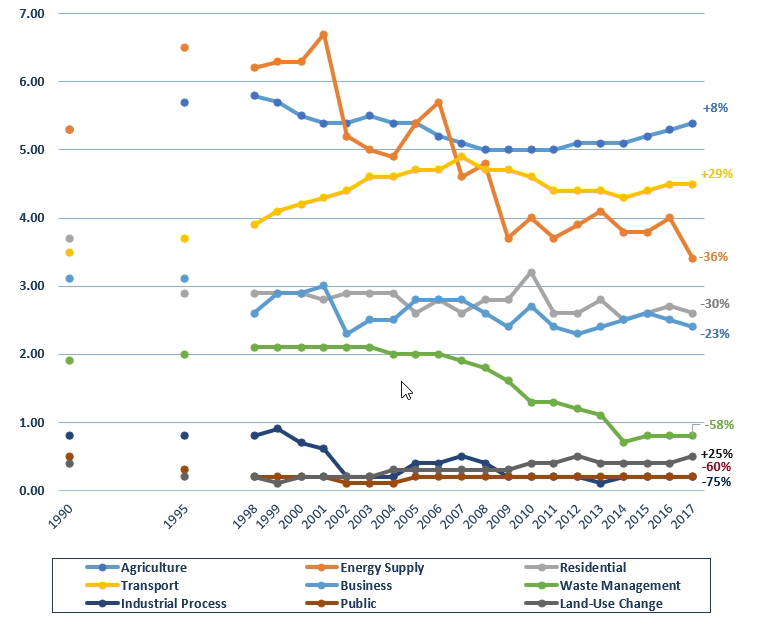

56. Over the past 30 years there has been an overall reduction in the GHG emissions from NI industry, with particular improvements evident in energy supply, waste management and business.

57. The below graph shows the annual GHG emissions broken down by economic sector between 1990 and 2017 with the percentage change over this timeframe:

Northern Ireland Grrenhouse Gas Emissions Per Year by Sector in Metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e)

Please Note – the above data does not encompass a change enacted in June 2021 with regards accounting for GHG emissions arising from peatlands/wetlands introduced by the Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) and other responsible departments across the UK

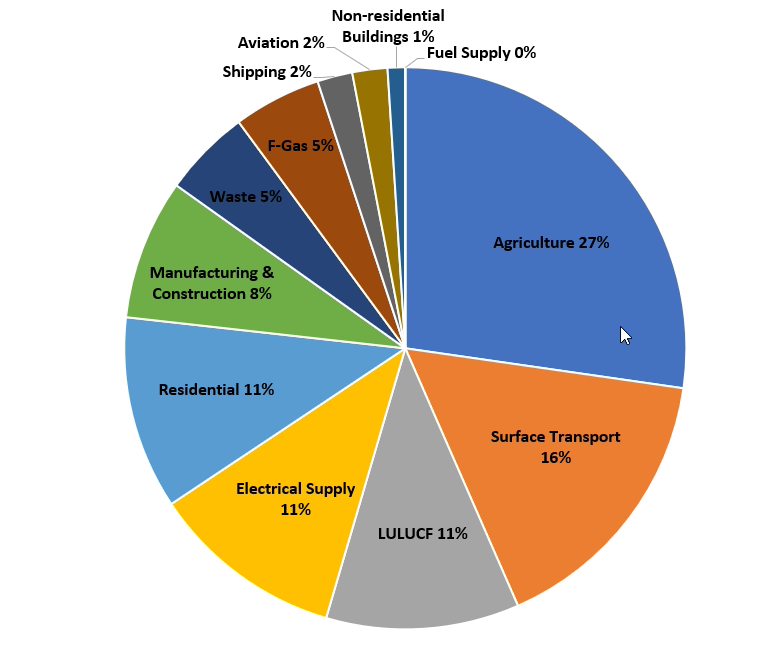

58. The biggest contributions to NI’s GHG emissions are from agriculture (27%), surface transport (16%) and Land-Use, Land-Use Change & Forestry (LULUCF) (11%). Emissions from agriculture and LULUCF are disproportionately higher than the UK averages of 10% and 2% respectively due to NI’s status as an important agri-food producer with high-levels of ruminant livestock that are known to contribute to methane emissions and the comparatively low-level of forest cover and relatively poor health of peatlands in NI, which limit the ability for carbon sequestration. Conversely, emissions from fuel supply (0%), manufacturing (8%) and aviation (2%) are much lower than the UK-wide averages, reflecting the specific characteristics of NI’s economy:

Northern Ireland Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector 2018 (taken from Committee on Climate Change's 6th Carbon Budget Report 2020)

7. CCC Advice on NI Climate Change Mitigation

59. As part of its Sixth Carbon Budget (2020) the CCC developed a range of potential pathways for the UK to mitigate GHG emissions by 2050 including “Headwinds” and “Tailwinds” scenarios that assumed progress on a lesser and more ambitious scale respectively.

60. As part of the “Balanced Net-zero Pathway” which is considered to be an achievable and credible route to deliver the emissions targets with an expectation of reasonable public engagement, behavioural change and policy development, the CCC envisages the following for NI:

- At least an 82% reduction in GHG emissions from baseline levels by 2050 to encompass net-zero CO2 emissions, i.e., NI will not achieve “net-zero” overall

- Annual GHG emissions will fall from around 23 MtCO2e in 2020 to 5 MtCO2e in 2050

- Emissions will fall by 54% compared to current levels by 2035

- The biggest reductions will come from the transport, residential building, LULUCF and electricity supply sectors

- Methane emissions from agriculture will dominate the NI emissions profile by 2050

- All GHG emissions must be reduced in NI to contribute to the UK-wide net-zero target and reductions must be made in terms of methane, as well as CO2 and other gases

61. In a letter to DAERA in April 2021, the CCC corroborated its recommendations for NI and explained why, in its estimation, it was not deemed feasible at this time to envisage an overall net-zero GHG position in NI by 2050:

“Net-zero for the whole of the UK by 2050 does not necessitate that every sector or area of the UK reaches absolute zero emissions by that date. Some parts of the UK will be net sources of greenhouse gases by 2050 with emissions offset in other parts of the UK that are net sinks.

Our analysis shows that Northern Ireland’s position as a strong agri-food exporter to the rest of the UK, combined with more limited capabilities to use ‘engineered’ greenhouse gas removal technologies means that it is likely to remain a small net source of greenhouse gas emissions – almost entirely for agriculture- in any scenario where the UK reaches net zero in 2050. It is fair that those residual emissions should be offset by actions in the rest of the UK.”

8. Climate Change (No.1) Bill

62. The Climate Change Bill that is being sponsored by an individual MLA (Private Member’s Bill) and was referred to the Committee for scrutiny on 11 May 2021 seeks to establish a legal basis for Climate Change mitigation in NI, and bridge the legislative gap between it and neighbouring jurisdictions.

63. The Bill comprises three Parts, 17 Clauses and two schedules. The composition, as drafted, is set out in the table below:

| Section | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Long Title |

Sets out the overarching objectives of the legislation to:

|

| Clause 1 |

Declares in law a “Climate Emergency” in NI and sets criteria by which this declaration may be rescinded by the Assembly |

| Clause 2 |

Establishes a legally-binding target for NI to deliver “a Net Zero carbon, climate resilient and environmentally sustainable economy by the year 2045” which covers the emission of all GHGs.

The emissions target year of 2045 cannot be delayed. It can however be brought forward, i.e., to achieve the target sooner than 2045, through a resolution of the Assembly.

Obligates The Executive Office (TEO) to lay before the Assembly Climate Action Plans (CAPs) on a 5-yearly basis that will document the initiatives to be delivered to make progress against the emissions target. |

| Clause 3 |

Sets out the contents of the CAPs which will include targets and measures to be achieved in each 5-year period:

Evidence and advice from the UK CCC as well as the IPCC and the ROI Climate Advisory Council must be used to set CAP targets.

Sectoral Plans must adhere to the following principles: “-Support growth of jobs that are climate resilient and environmentally and socially sustainable

-Support net-zero carbon investment and infrastructure

-Create work which is high-value, fair and sustainable

-Reduce inequality

-Reduce, with a view to eliminating, poverty and social deprivation” |

| Clause 4 |

Establishes that annual reports must be laid to the Assembly with an assessment of the progress made against the CAP targets |

| Clauses 5 and 6 |

Provide for the establishment of a new Climate Office in NI, led by a Commissioner and supported by a secretariat – an independent corporate body to oversee and review the working of the legislation |

| Clauses 7 and 8 |

Outline the process for the appointment of the role of the Commissioner and how vacancy of the position is to be managed |

| Clause 9 |

Sets out the core functions of the Commissioner who will be responsible for:

|

| Clause 10 |

Provides for the Commissioner’s powers in relation to accessing information. The Commissioner will have the authority to access any relevant documents as necessary in the discharge of his/her duties. Any person holding such documents must make them accessible to the Commissioner |

| Clause 11 |

Sets out that TEO must submit a report to the Assembly within two months of an annual CAP progress report being laid that provides commentary on the attainment (or otherwise) of the targets/sectoral plans and considerations of any proposals put forward by the Commissioner |

| Clause 12 |

A “non-regression” principle, setting out that there should not be any implicit or explicit regression in the future from environmental or climate related protections or regulations that were in force in NI as at 31 December 2020 (the transition date when the UK formally left the European Union) |

| Clauses 13-17 |

Non-substantive clauses covering definitions, interpretations, enforcement date etc. |

| Schedule 1 |

Provides further details of the composition, staffing, budget allocation and accounting requirements of the Climate Office |

| Schedule 2 |

Lists the organisations from which a potential appointee to the role of Climate Commissioner is prohibited from being an employee of |

9. Committee’s Consideration of the Bill

Bill Timeline

64. The Bill was introduced to the Assembly and passed First Stage on 22 March 2021.

65. At its meeting on 29 April 2021 the Committee received oral evidence from the Bill Sponsor Ms Clare Bailey MLA.

66. Second Stage was completed on 10 May and Committee Stage began on 11 May 2021.

67. On 13 May the Committee agreed proposals for a call-for-evidence. It also agreed to submit a motion to the Assembly seeking an extension of Committee Stage to December 2021 in order to facilitate time to carry out effective scrutiny.

68. The Committee’s template to collate evidence and views from stakeholders was launched on 20 May 2021 on the Citizen Space platform (with a closing date of 15 July 2021), supported via signposting ads placed in local newspapers and extensive social media messaging.

69. The Committee’s motion was approved by the Assembly on 24 May 2021 that, in accordance with Standing Order 33(4), Committee Stage would be extended to 17 December 2021.

70. At its meeting on 27 May 2021 the Committee received a briefing from officials from DAERA on their views on the Bill.

71. The Committee received oral evidence from the Woodland Trust, the CCC and AFBI on 10 June 2021.

72. Further oral briefings were provided on 16 June 2021 from Climate NI and NI Environment Link via an ad-hoc, entirely virtual, meeting.

73. On 17 June 2021 the Committee facilitated two stakeholder events to allow interested parties to come together and discuss some of the salient aspects of the Bill. The morning session provided an opportunity for representatives of key stakeholder organisations to discuss the issues and the evening event was organised specifically for representatives from youth organisations including the Young Farmer’s Clubs of Ulster, the Commissioner for Children and Young People and Belfast Climate Commission. Participants were divided into cross-organisation virtual breakout rooms to consider three questions before providing feedback to the group at large.

74. At its meeting on 24 June 2021 the Committee received oral briefings from the NI Meat Exporters Association, Dairy Council NI and the UK Carbon Capture and Storage Research Centre (UKCCSRC) about their considerations of the Bill.

75. Further oral evidence was provided by the Ulster Farmers’ Union, Dr Andrew Jackson from University College Dublin (UCD) and Professor Peter Thorne (Maynooth University) on 1 July 2021.

76. Following resumption of Assembly business after the summer recess, Members received a briefing on 9 September 2021 in relation to an analysis of the returns to its call-for-evidence activities undertaken between May and July 2021. It also heard oral evidence from the Federation of Small Businesses on this date.

77. On 16 September 2021 oral briefings were provided by the Northern Ireland Local Government Association and Chartered Institute of Wastes Management, and the following week from the Environmental Justice Network.

Research and Information Service

78. The Committee commissioned three research reports from the Assembly’s Research and Information Service (RaISe) to support its considerations:

- 13 May 2021 the Committee received an oral presentation from RaISe on the Research Paper - Private Member Bill: Climate Change Bill 2021

- 9 September 2021 – RaISe provided a briefing to Members on the nuances of biogenic methane and how this particular gas is accounted for within Climate Change legislation

- 25 November 2021 – the Public Finance Scrutiny Unit presented their considerations of the potential costs to the NI economy of pursuing different Climate Change targets

Call-for-Evidence Responses

79. The Committee facilitated a range of activities in order to seek views and perspectives from members of the public and stakeholder organisations on the Bill given the significant and cross-cutting nature of the proposed legislation, as well as its potential impact on all sectors of the local economy and for future generations, including:

- A call-for-evidence template was made available on the Citizen Space platform between 20 May and 15 July 2021: 126 returns were made- 79 from members of the public and 47 from organisations

- Other free-format written submissions were sent to the Committee’s public email address during this time period that included 6 individual responses, 30 organisational returns and 1,145 messages of support via the Friends of the Earth website

- Stakeholder events held on 17 June 2021 with 44 participants representing a range of organisations to discuss the Bill, its objectives and potential impacts

- Focus Groups facilitated by the Assembly’s Education team with 16 primary and post-primary schools and over 300 pupils participating

80. The full details of the themes arising from the call-for-evidence are outlined in a separate report, but the key messages are summarised below:

- The majority of respondents were broadly positive about the aims and objectives of the Bill and welcome the introduction of Climate Change legislation for NI which is considered to be long overdue

- Most returnees support the declaration of a Climate Emergency

- There was a difference of opinion regarding the 2045 net-zero target with some respondents considering this to be an effective way of driving change through an ambitious target and others expressing concern that it was unworkable and not in line with advice provided by the CCC

- A significant proportion of participants reflected on the potentially ruinous impact on the local agri-food sector should the 2045 net-zero target be enacted

- There was broad support for the establishment of an independent Climate Office and Commissioner to hold government accountable with appropriate and sufficient powers. The need to ensure clear lines of responsibility for this Office to the Assembly and to other entities such as the CCC was highlighted

- The concept of establishing CAPs with specific sectoral targets was well-received as a potentially effective pathway

- It was acknowledged that there will be a differential impact on sectors of the economy in terms of their ability to reduce carbon emissions

- The significant challenges for the local agri-food sector were recognised and it was felt that this industry in particular would require support

- A universal message from stakeholders was that Just Transition needs to be central to the legislation

- It was strongly advocated that multi-year budget planning is essential to deliver the emissions targets and support implementation of the CAPs

- CAPs must be subject to Rural Impact Assessments

- The current planning application and approval system is a significant constraint in terms of progressing with investment and implementation of infrastructure to support Climate Change

- Transboundary considerations are important as Climate Change is a global issue and local entities should work with colleagues in neighbouring jurisdictions

- A number of respondents considered that the Bill should be expanded to include a specific requirement on government to ensure climate adaptation processes are legislated for, with inclusion of a specific definition and possible responsibility on Public Bodies

- Land Use – a frequently highlighted issue was the need for a comprehensive strategy for land use in NI in order to ensure that space is identified and nurtured to support carbon sequestration

- Public Engagement – a key message reflected by a number of participants was the need for a robust system of continuous public education and awareness in relation to Climate Change

Oral Evidence Sessions

81. The Committee invited a wide range of organisations between May and September 2021 to provide oral evidence regarding their views on the Bill and the below paragraphs summarise the key points arising from these sessions.

a) Bill Sponsor Team

82. Ms Clare Bailey (MLA) and representatives from Climate Coalition NI who helped draft the Bill attended the Committee on 29 April 2021 and presented its overarching aims and salient components:

- To declare a Climate Emergency

- Facilitate a programme of Climate Change mitigation and adaptation

- Ensure a net-zero GHG target by 2045

- Establish a system of 5-yearly action plans

- Provide for an independent Climate Commissioner

83. Ms Bailey explained that the Bill’s purpose was to establish a robust legislative basis from which to develop climate policy in NI:

“The Bill sets out a substantive pathway to decarbonisation for Northern Ireland, ensuring that there is transparency and democratic oversight at every stage, and guaranteeing independent monitoring so that that oversight can be effective.”

84. The evidence underlying the 2045 net-zero target was discussed in the context of the CCC’s advice that NI can only be expected to deliver at least an 82% reduction by 2050. It was explained that numerous advisory bodies have stated that the current trajectory of global emissions reduction will be insufficient to meet the Paris Pledge and therefore there is a need to pursue more ambitious targets to prevent further climate damage: as a result, there is considered to be a scientific evidence-base for more stringent climate action.

85. Members questioned the Bill team about the effect the 2045 target could have on the agri-food sector. While it was acknowledged that there will undoubtedly be challenges for local farmers in moving towards climate-friendly practices, the consequences, both financial and otherwise, to the industry of not taking action would far outweigh costs of the necessary change.

86. The issue of cross-border working was highlighted as a key feature of the Bill as it provides a role for existing North/South bodies to play a part in transboundary policy development, albeit it does not place any specific duties on these organisations.

87. The role of the proposed Climate Commissioner, who will provide an important reporting and advisory function for the Assembly, was explained:

“the Assembly needs an independent source of expert evidence, and it needs to be as well informed as possible so that it can debate as well as it can whether it should approve any changes or climate action plans that are brought forward. The climate commissioner would act as the nodal agency to provide the Assembly with on-the-ground-evidence about what is going right, what is going wrong and what can be improved.”

b) Climate Experts and Academics

88. Lord Deben, Chairperson of the UK CCC attended the Committee on 10 June 2021 and outlined the CCC’s view in relation to what is an achievable and realistic proposition for NI in terms of reducing emissions. Lord Deben reaffirmed the CCC’s advice that a GHG reduction of at least 82% from baseline levels by 2050 is the most ambitious, achievable target that can reasonably be considered for NI given present circumstances, knowledge and capabilities.

89. The CCC reflected that an 82% 2050 reduction would be extremely challenging for NI to deliver, particularly given its status as a large agri-food producer, and that it was considered a robust target to hold the Executive accountable for.

90. “In looking at the whole of the United Kingdom, we are committing to net zero in 2050. As for the constituent nations of the United Kingdom, each has a different problem, and each has more or fewer opportunities. It will all have to add up to net zero…. we come to look at Northern Ireland, and we have recognised that the particular problems mean that it cannot reasonably be sure of reaching net zero by 2050 but can do 82%. That is a tough demand. Do not, for one moment, think that we are asking something small. Secondly, because we do it in that way, we expect you to reach that target. It is not a kind of hopeful, wish-list figure; it is a necessary part.”

91. When questioned if it was likely that the CCC would bring forward the UK’s net-zero target year, Lord Deben articulated that the current position is as ambitious as it can be - “I have a proper and statutory duty to say that I do not believe that the United Kingdom as a whole could do it more quickly than by 2050 in current circumstances.”The need to set challenging, but achievable targets, was reflected and that there could be negative consequences associated with being overly ambitious to pursue goals that are simply unrealistic.

92. However, it was acknowledged that the UK target could be revised in the future if it becomes evident that new technologies could be exploited, and relied upon, to reduce GHGs, for example development of carbon sequestration in sinks off the North Sea.

93. In relation to agriculture, the CCC reflected that wholescale change was needed across the sector in order to reduce emissions and whilst this may require some reduction in livestock numbers, other measures could help to improve the efficiency on farm holdings including optimising feeds and health of animals. Lord Deben advised that the CCC anticipates an approximate 20% reduction in demand for meat across the UK in the next ten years, and that people should be encouraged to eat high-quality meat that has been responsibly produced. The potential for the importation of products from other parts of the world that have lower environmental standards should be avoided at all costs.

94. Lord Deben reflected that it would be important for NI to attain its emissions goals in order to attract investment from private enterprise and to maintain its reputation for high-quality and responsible agri-food production.

95. The importance of facilitating effective incentivisation schemes and a Just Transition was strongly expressed: “we will have to have a just transition within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland so that the poorest do not pay a bigger burden.”

96. Professor Peter Thorne from Maynooth University, who specialises in the field of Climate Governance, welcomed the Bill’s introduction, felt that the inclusion of biodiversity targets within the CAPs was laudable and that the establishment of an independent Climate Office would provide the opportunity for strong governance and accountability.

97. However, Professor Thorne felt that the Bill could more clearly define the role and expectations of government departments and that there needs to be an explicitly designated lead department with overall responsibility. Professor Thorne also considered that there was an opportunity to provide greater focus on climate adaptation to ensure that future planning and infrastructure is appropriate for the already changed climate.

98. In relation to emissions targets, Professor Thorne broadly supported the advice of the CCC that net-zero by 2050 for the UK as a whole was a reasonable goal.

99. Dr Andrew Jackson from UCD expressed strong support for the Bill and in particular welcomed the incorporation of biodiversity targets and the ambition to deliver net-zero emissions by 2045. Dr Jackson articulated his view that ambitious targets are the most effective mechanism to drive change and that there should be a continuous process of evaluation to ensure that emissions goals are as high as they possibly can be.

100. In relation to the potential societal and economic impact of net-zero by 2045, Dr Jackson recognised that there could be adverse effects but that, given the seriousness of the climate emergency, forceful action was necessary and it was unrealistic, and potentially unethical, to rely on speculative carbon capture technologies that have not yet been proven at scale to deliver emissions reduction.

101. In order to offset the potential consequences for industry, Just Transition and Climate Justice principles should be at the heart of policy. Dr Jackson also expressed a preference for a more stringent and frequent reporting mechanism to produce monthly reports on the progress made by institutions in delivering targets.

102. Professor Jon Gibbons from the UKCCSRC provided evidence on the potential use of carbon capture and storage and generation of alternative energy sources to mitigate emissions. The development of these technologies is seen as crucial to delivering the net-zero position for the UK by 2050.

103. Professor Gibbons outlined that it was very important to exploit opportunities for carbon capture and storage where it is technically feasible to deliver, as these methods are a potentially viable pathway to have “net-negative” emissions. It will not be possible to deploy these technologies on a widespread basis as they require access to natural undersea sinks with appropriate sedimentary cover to facilitate large-scale CO2 capture.

104. The below map, adopted from the CCC’s Sixth Carbon Budget, shows the potential CO2 storage sites located across the UK continental shelf:

105. Professor Gibbons cautioned against pursing an overly ambitious net-zero target by 2045 given the fact that NI does not have the geographic or geological infrastructure necessary to facilitate direct-air-capture and storage of CO2 and therefore would have to rely on more deep and extensive reductions in other areas, such as agri-food, to try and meet this target. Professor Gibbons reflected that the UK’s overarching aim to deliver net-zero by 2050 was laudable and explained the potential to facilitate carbon-capture and storage in the North Sea would be crucial to this, and that NI should contribute to the overall aim: “the 82% target set by the Committee on Climate Change…should be taken extremely seriously.”

106. The viability and purpose of the proposed Climate Office was questioned, and it was suggested that the Assembly’s role and links with the CCC could be strengthened as a means of having independent oversight of Climate Change mitigation in NI.

107. While it will not be possible to facilitate natural CO2 storageand capture in NI, Professor Gibbons advised that it would be theoretically possible to ship NI’s CO2 to suitable locations where it could be re-engineered as biomass energy. Such models have been used in Scandinavia to reduce emissions, but come at a high economic cost.

108. Dr Ciara Brennan and Dr Thomas Muinzer, representing Environmental Justice Network Ireland (EJNI) provided evidence on 23 September. EJNI welcome the Bill’s introduction and see it as an important step in overcoming NI’s reputation as an “environmental laggard.” Dr Brennan explained how the province’s constitutional legacy of Direct Rule followed by spasmodic episodes of devolved governance has led to a series of disjointed and ineffective regulatory systems. In EJNI’s opinion this has contributed to sub-optimal environmental governance in NI and the manifestation of poorer biodiversity health and examples of significant environmental damage.

109. The highly ambitious net-zero target provides the opportunity to overcome this negative stereotype and sends a major signal of intent to members of the public and other jurisdictions on the importance that local institutions place on mitigating Climate Change.

110. In relation to establishing an emissions target, EJNI argue that this is ostensibly a political decision but should be “legally informed” via benchmarking the legislative provisions in place in other jurisdictions. Given that all of NI’s immediate neighbours have, in some form, legislated for a net-zero position by 2050 and this aim has been adopted by countries across the European Union, EJNI consider that this be the minimum emissions goal that should be included in the Bill in order to avoid jeopardising NI’s reputation and perception from other countries in relation to its Climate Change commitments.

111. Further, it was explained that there could be a risk to the local economy and industries if a less stringent emissions target is implemented. This may inadvertently lock-in a competitive disadvantage for NI in relation to attracting investment, exports of its produce and trade, in comparison to its neighbours.

112. The efficacy of a net-zero target in terms of policy clarity was discussed because it sends clear messages to public bodies, companies and citizens of the overarching goal. Any dilution or quantification of a target may lead to confusion and ambiguity about future strategy.

113. When questioned on the advice provided by the CCC, that NI can realistically achieve an “at least 82%” net-position by 2050, EJNI reflected that the CCC is a highly credible and respected advisory body and that its guidance should not be ignored. However, it was highlighted that there are other sources of advice available and that the CCC’s projections undertaken as part of its Sixth Carbon Budget were bound by certain methodological constraints.

114. In relation to NI’s extensive agri-food sector and the projected damage to the industry resultant from a net-zero target, EJNI argued that a “Just Transition approach” at governmental level needs to be adopted. In EJNI’s view this means that if there are circumstances in specific sectors of the economy that are deemed to be particularly complex or challenging in relation to reducing GHGs, there should be focussed and targeted action from the UK Government supported by appropriate resourcing, to off-set this, and not simply manage it as “a case of exceptionality.”

115. EJNI argue therefore that it is incumbent on the Executive to engage with, and lobby, the UK Government to support additional and extra measures to reduce local emissions output, without devastating the agri-food industry.

116. The inclusion of biodiversity targets as part of the sectoral plans was welcomed as a sophisticated and novel aspect of the legislation, as is the proposed establishment of an independent Climate Office. It was explained that in some quarters there is a perceived lack of trust with existing environmental oversight bodies due to their strong links to DAERA – an entirely independent entity was seen as a potentially positive mechanism to ensure strong, objective accountability.

c) Environmental Sector

117. Representatives from Northern Ireland Environment Link (NIEL) provided oral evidence on 16 June 2021. NIEL welcome the Bill’s introduction and expressed strong support for its aims and overarching objectives. In particular, NIEL felt that the 2045 net-zero target was very positive and necessary for the following reasons:

- NI currently has the 13th highest GHG emissions per capita in the world and therefore needs to take ambitious action in order to deliver its fair contribution to mitigation

- While the CCC has advised that NI can reach at least an 82% reduction in GHGs by 2050 as part of its “credible pathway”, there is nothing technically limiting NI’s ability to reach net-zero

- A net-zero target provides clarity for government, businesses and the public at large as to what needs to be delivered

- Provision for a net-zero target by 2045 aligns with Climate Change legislation in Scotland and Wales

118. NIEL also expressed strong support for the establishment of a Climate Commissioner and felt that this role would be crucial in liaising with advisory and oversight bodies in ROI to ensure harmonisation of policy approach across the island of Ireland. The inclusion of biodiversity targets in the CAPs was also seen as a strength as this recognises the knock-on effect climate damage has had on water, air and soil quality.

119. Like other stakeholders, NIEL highlighted the need for Just Transition for different parts of the economy, particularly the agri-food sector, and suggested that there was viable opportunity to modernise the system of local farm payments to incentivise nature-friendly practices.

120. Similarly, NIEL outlined the opportunities for other sectors arising from the Bill including the potential for significant jobs growth in green industries through retrofitting of buildings, insulating homes and the shift to renewable technologies. The potential to harness NI’s natural capabilities to become a world-leader in renewable energy was discussed, particularly in relation to the exploitation of wind, tidal and wave power.

121. Climate NI also support the Bill and consider that urgent action is required by all governments, including the local administration, to mitigate the negative effects of Climate Change and to prevent longer-term costs both environmentally and economically:

122. “An overall message to the Committee is this: the best time for us to take climate action was, of course, in the past, but the next best time is now….. Northern Ireland needs to act now by front-loading cutting carbon and preparing for the Climate Change that is already locked in.

Delays will cost money, lead to lost opportunities and cause damage, including loss of life, property and nature, locally and further afield.”

123. In relation to the 2045 net-zero emissions target, Climate NI articulated that the certainty provided by a “net-zero position” is of utility in and of itself for policy-makers, even if it may not be deliverable, “we recognise that the CCC has provided guidance on a target of at least 82% for all greenhouse gases, with the potential for almost reaching net zero for CO2 by 2050. However, the clarity of communication on a net zero target is something to be considered, even if Wales and Scotland are not currently hitting their targets.”

124. The scope of the proposed CAPs to include biodiversity targets was broadly supported, but it was suggested that the Executive should be obligated to prepare an emergency CAP, should delivery of targets be missed.

125. Climate NI strongly support an amendment to explicitly reference adaptation requirements and consider that this should be given equal footing to mitigation. Relatedly, it was suggested that a mandatory adaptation responsibility for major public bodies, similar to what is included in Scottish legislation, should be added to the Bill and be augmented by a voluntary adaptation reporting scheme for civil society. Climate NI explained that, in their view this is essential in order to drive change, so that these entities are obligated to disclose publicly how they are improving resilience to climate impacts that are already “locked in” and cannot be reversed.

126. A further area of focus addressed by Climate NI was the need to ensure sufficient resources to support policies via multi-year strategic budgetary planning. It was suggested that there should be some form of independent oversight, for example from the CCC or the Climate Commissioner, in terms of scrutinising the budgets set by government to support Climate Change strategy.

127. In terms of Just Transition, Climate NI considered that: “it is essential to have a just transition as part of the Climate Change Bill and to use Scottish principles of a just transition, which take into account regional economies and societies.”

128. The Woodland Trust articulated support for the Bill and its main components, highlighting that while the declaration of a Climate Emergency was important, it was crucial to widen the scope of this to include an eco-system emergency in order to reflect fully the damage caused to the environment.

129. The Trust support the ambition of the Bill’s emissions target, but noted that it would defer to the advice of the CCC as the recognised competent authority in provision of expert advice.

130. The importance of enhancing the health and strength of NI’s forests and land was strongly expressed by the Trust as a means of mitigating GHG emissions in the future. These natural resources have the potential to sequester large amounts of CO2 from theatmosphere, thereby off-setting, and possibly neutralising, emissions from industry, farming, travel etc.

131. However, the Committee heard of the significant challenges in terms of exploiting the sequestration potential of NI’s land including the fact that NI currently has only 8% forestry cover, and that this should be closer to 18% in order to harness CO2 capture.Further, the vast majority of tree cover, about 63%, comprises non-native species, which are less effective in terms of sequestration than naturalised trees.

132. Other barriers include the ability to purchase land and education of land owners to actively reforest and rewild their plots. The benefits and success of initiatives such as the Forest Expansion Scheme were communicated, as was the need to ensure that there are viable incentivisation schemes for farmers to reforest their holdings.

133. The Trust called for an effective and comprehensive Land Use Strategy to establish a strategic policy position to both help reduce GHG emissions, and restore the health of the natural environment.

d) The Agri-Food Sector

134. The Ulster Farmers’ Union (UFU) outlined the scale of the NI agri-food sector and its wider importance to the economy, which generates approximately £5.2 billion per annum, supports over 113,000 jobs and is driven by the work and output of around 24,000 farmers.

135. The importance of adopting practices in order to address Climate Change was acknowledged but it was conveyed that this should be balanced with the need for the continued production of high-quality food:

136. “The UFU supports Climate Change legislation and the need to tackle emissions from agriculture, but proposals must be fair, credible, backed by relevant evidence and deliver a just transition for everyone.

While Northern Ireland must reduce its impact on the climate, we should not reduce our capacity to produce high-quality, affordable food to high environmental and animal health and welfare standards.

Global demand for food is increasing. According to UN forecasts, the number of mouths to feed will rise to nearly 10 billion by 2050. The Climate Change agreement, the Paris agreement, set ambitious Climate Change targets but also recognised the importance of safeguarding food security and ending hunger.”

137. The UFU warned against any mitigation measures that would lead to a reduction in output from the agri-food sector, which would leave it unable to meet this growing demand.

138. In relation to the Bill, the UFU rejected the net-zero 2045 emissions target and advocated that the CCC’s recommendations should be adhered to, albeit they themselves will present a significant challenge for local farmers. “The CCC recommended an 82% reduction by 2050. That is not an easy option. It is a huge challenge for us as an agriculture sector.”

139. The 2045 net-zero target represents, in the UFU’s view, a significant threat to the local agri-food industry as it would necessitate a drastic reduction in ruminant livestock holdings. The UFU articulated the ruinous impact such a reduction would have on the sector, and wider economy, with inevitable job losses and socio-economic deprivation in rural areas. The UFU strongly urged the Committee to follow the advice of the CCC when considering the emissions targets.

140. In addition to the social and economic impacts, the UFU highlighted that the 2045 target could cause negative consequences for the environment. The UK self-generates only about 60% of its current total calorific requirement. If the NI agri-food industry, which is a net exporter to Great Britain, were to significantly reduce its output as a result of pursuing net-zero by 2045, greater amounts of food and produce would have to be imported from overseas, with an associated carbon footprint. This unintended “carbon leakage” would contribute to global warming and perhaps off-set any benefit gained from reducing methane emissions from local livestock.

141. The UFU vociferously rejected the proposition of having an independent Climate Commissioner and cautioned that establishment of any such office would have to be implemented within a clear framework to ensure accountability to a responsible entity, such as the Assembly, and to avoid gratuitous use of the powers conferred on the Commissioner.

142. It was suggested that a Just Transition Commission, similar to what has been legislated for in Scotland, should be established in NI as part of any Climate Change law in order to ensure that the interests of farmers and rural communities are protected and taken into account when making plans.

143. The UFU suggested that the Committee undertake closer analysis of the impact of biogenic methane and how it differs from other gases due its comparatively short life. The potential for treating biogenic methane differently within the legislation, as has been done in other jurisdictions, was discussed but ultimately the UFU reflected that it was indifferent to having a separate target.

144. A concern was raised about the existing methods of attributing carbon sequestration to different sectors. At present, all sequestration that takes place on farm holdings is allocated to the LULUCF inventory and therefore the contribution that individual farmers, and the sector as a whole, make in relation to off-setting emissions is not readily apparent. The UFU suggested that there needs to be an improved, and more granular, mechanism of accounting for carbon sequestration on farms, as some sites may currently be “net-zero”, but they have no way of knowing this for certain.

145. The Northern Ireland Meat and Dairy Exporters Association (NIMEA) provided evidence on 24 June 2021 and voiced strong concern at the potential devastating impact that the Bill could have on local producers.

146. NIMEA reflected the concerns raised by UFU in relation to the 2045 net-zero target and highlighted that it would compound the economic threats to local agri-food producers as a consequence of the Free Trade Agreement signed by the UK Government and Australia. In NIMEA’s opinion this could lead to cheaper meat, which is produced in a country which does not have a net-zero target, being shipped across the world to off-set loss of local food production:

147. “We argue that, if the Assembly passes the Bill, it will be complicit in exacerbating those Brexit-related impacts. It would decimate our industry, which is starting off well ahead of international competitors who will see the Bill as a fantastic opportunity to replace us in the UK market. You need to make sure that that does not happen, because it is not in the interests of your constituents, our economy, our food security or the environment. We have demonstrated that only coordinated global action will address Climate Change. Uncoordinated action by small countries or, in this case, regions of small countries will make a negligible difference to the entire issue and, in fact, could be counterproductive.”

148. The importance of engaging with, and encouraging, farmers to adopt environmentally-friendly practices to enhance carbon sequestration on their holdings was discussed, for example through genetic selection to have less emissive animals, better feeding solutions and methods to convert methane emissions to water vapour that could be used as a renewable energy source.

149. NIMEA were critical of the fact that the Bill had not been subject to a rural or economic impact assessment before its introduction to the Assembly.

150. A similar concern was raised by the Dairy Council that criticised the use of a Private Member’s Bill to bring forward far-reaching legislation:

151. “Our issue is not with the need for a Climate Change Bill for Northern Ireland but rather that, as a parliamentary tool, a private Member's Bill is not fit for the purpose. A Bill dealing with something as important as Climate Change should be based on robust scientific evidence and should have been subjected to a proper process of consultation, impact assessment and analysis. That is not the case with this Bill. The targets that a Climate Change Bill will set will be achievable only with the cooperation of industry. The Northern Ireland Assembly needs to be aware that, by embarking on such a journey on the basis of this private Member's Bill, in sporting parlance, it risks losing the changing room and precipitating a loss of the industry's confidence in the Assembly's leadership on the matter.”

152. The Council explained that the local dairy sector is worth approx. £1.5 billion, accounts for 20% of the UK’s milk output and exports to over 80 countries worldwide.

153. The Committee was told that the net-zero 2045 target could precipitate the decline of the NI dairy sector to“a cottage industry”, as the enforced reduction in cow numbers necessary to meet the emissions goal would inevitably decrease throughput in milk-processing facilities, leading to site closures and job losses.

154. Like other representatives of the agri-food sector, the Council reflected that the Bill could potentially contravene the United Nation’s sustainability principles through reduction in food output and the associated consequence of having to import products from elsewhere.

155. The Council considered that the CCC’s recommendation would be preferable to the 2045 net-zero target, but that this would still present significant challenges for the industry, necessitating an approximate 20% decrease in livestock holdings. This would compel the local dairy sector to become more efficient in order to meet the demand for its products with less source cattle.

156. “We need to make sure that we can find ways of continuing to maintain our milk production with fewer animals while meeting the future demands of our customers.”

157. On 16 August 2021 groups representing the agri-food sector, including the UFU, the Livestock and Meat Commission, NIMEA, the Dairy Council, the Northern Ireland Grain Trade Association and the Pork and Bacon Forum, along with other bodies, published a report that they had collaboratively commissioned from KPMG to scope the potential impact of the Bill for the industry.

158. The report assessed the economic impact on local farms and the consequences for rural areas that could be manifest if the 2045 net-zero target was pursued.

159. The analysis followed the CCC’s “Tailwinds” scenario (most ambitious emissions projection for 2050) as its foundation, and accelerated the trajectory of future emissions by 5 years to give a projection of the potential emissions account in NI in 2045. This was measured against the CCC’s “Baseline” (business as usual) pathway to facilitate comparison.

160. The key findings of the report are as follows:

- By 2045 there would be a residual GHG emissions account in the NI agriculture sector of 1.19 MtCO2e, compared to 6.40 MtCO2e in the Baseline – an additional reduction of 81%

- The vast bulk, around 92%, of the required agricultural emissions reduction would come from reducing livestock numbers

- It is projected that beef cattle, dairy cattle and sheep herd numbers would fall by 86% from 2021 levels, with an 11% reduction in pig and poultry livestock

- Given the composition of local farms, with the vast majority being small, family-owned holdings, and slim profit margins, any decline in output over 10% for many beef farms, 30% for sheep and 50% for dairy sites presents significant viability challenges

- It is therefore estimated that the herd reductions would lead to a decrease of 21,150 operational farms in NI (compared to 2021), with beef and sheep farms in less favoured areas being most profoundly impacted

- The herd reductions and farm closures will have a significant economic impact with the following downturns expected across different strands of farming:

| Sector | Economic Output 2021 (£m) | Economic Output 2045 (£m) | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beef |

583 |

210 |

-64% |

| Dairy |

748 |

252 |

-66% |

| Sheep |

113 |

50 |

-56% |

| Pig |

255 |

215 |

-16% |

| Poultry |

627 |

578 |

-8% |

| TOTAL |

2,326 |

1,305 |

-44% |

e) Government Departments and Arm’s Length Bodies

161. Officials from DAERA provided their assessment of the scope, merits and shortcomings of the Bill on 27 May 2021. DAERA outlined that the CCC is the primary, competent source of expertise and that their assessment as to what is achievable in NI should be the driving force behind policy development. DAERA therefore support the CCC’s recommendation that NI should aim to reduce emissions by at least 82% by 2050, which represents a fair, proportionate contribution to the UK-wide net-zero goal.

162. DAERA highlighted that a more stringent target over and above what the CCC has recommended would cause significant disruption and damage to the local economy, with the agri-food sector most profoundly affected. The Committee heard that this would lead to an additional emissions benefit of only 0.73% and questioned the efficacy of pursuing such an ambitious target, given the impact it would have on the local agri-food industry.

163. The need to ensure that there is flexibility within the legislation was highlighted so that policy can be adapted in line with science, evidence and technology that will emerge in the coming years. Officials gave an example of the change in emissions accounting methodology that was introduced in 2021 that has led to emissions from degraded peatland being included for the first time – this has added approx. 2 megatons of CO2 into the annual NI emissions account.

164. The additional costs of achieving the aims of the Bill were raised as a concern and how this would be resourced. Based on estimates provided by the CCC, it is projected that an additional £900m in funding would be required for NI to deliver net-zero by 2045, compared to the “Balanced Pathway” route.

165. The Committee was briefed by representatives from the Agri-food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) that highlighted some of the on-going work being undertaken locally to research innovations that may help mitigate Climate Change.

166. AFBI contributed to a multi-organisation consortium of scientific and research institutions that assessed the UK livestock industry’s potential to deliver net-zero emissions: “The overriding consensus from that meeting…was that it will be very challenging, due to the physical and biological nature of livestock, particularly ruminants. Whilst there are tools and solutions at the minute that will take us some of the road, as well as the sequestration that we can realise from our land through forestry, agroforestry, hedgerows etc, it will be very challenging.”

167. The importance of enhancing biodiversity health in terms of water and soil quality was articulated, as these are essential in order to ensure that natural methods of carbon sequestration are maximised.

168. AFBI provided an overview of some the work and projects that it is involved in that may help to mitigate emissions from ruminant livestock including:

- Efficacy of dietary additives that may reduce methane

- Reducing farm waste

- Earlier detection of ill-health in livestock

- Use of additives to reduce emissions from slurry

- Covering slurry tanks

- Use of anaerobic digestion to drive circular nutrient use