Report on the Committee's Inquiry into the Criminal Justice Services available to Victims and Witnesses of Crime in Northern Ireland

Session: 2011/2012

Date: 21 June 2012

Reference: NIA 31/11-15

ISBN: Only available online

Mandate Number: 2011/15 Second Report

Committee: Justice

7890.pdf (16.81 mb)

Committee for Justice

Report on

the Committee's Inquiry into the Criminal Justice Services available to Victims and Witnesses of Crime in Northern Ireland

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings, Minutes of Evidence, Written Submissions and Other Memoranda and Papers relating to the Report

Ordered by the Committee for Justice to be printed 21 June 2012

Report: NIA 31/11-15 Committee for Justice

Mandate 2011/15 Second Report

Membership and Powers

The Committee for Justice is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, Section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Standing Order 48.

The Committee has power to:

- consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- consider relevant subordinate legislation and take the Committee stage of primary legislation;

- call for persons and papers;

- initiate inquires and make reports; and

- consider and advise on any matters brought to the Committee by the Minister of Justice.

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The membership of the Committee during the current mandate has been as follows:

Mr Paul Givan (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Mr Stewart Dickson

Mr Tom Elliott[1]

Mr Seán Lynch

Mr Alban Maginness

Ms Jennifer McCann

Mr Patsy McGlone[2]

Mr Peter Weir

[1] With effect from 23 April 2012 Mr Tom Elliott replaced Mr Basil McCrea.

[2] With effect from 23 April 2012 Mr Patsy McGlone replaced Mr Colum Eastwood.

Table of Contents

List of abbreviations and acronyms used in the Report

Report

The Status and Treatment of Victims and Witnesses

Single Point of Contact – Witness Care Units

Communication and Information Provision

Collation of Information/Research on the Experiences of Victims and Witnesses

Support Provisions and Special Measures

Delay in the Criminal Justice System

Key Findings and Recommendations

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

Appendix 3

Written Submissions

Appendix 4

Northern Ireland Assembly Research Papers

Appendix 5

Memoranda and correspondence from the Department of Justice

Appendix 6

Additional papers considered by the Committee

List of abbreviations and acronyms used in the Report

CAJ Committee on the Administration of Justice

CJINI Criminal Justice Inspection Northern Ireland

DoJ Department of Justice

FLOs Family Liaison Officers

IDVAs Independent Domestic Violence Advisors

ISVAs Independent Sexual Violence Advisors

NICEM Northern Ireland Council for Ethnic Minorities

NICTS Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunals Service

NIPB Northern Ireland Policing Board

NIVWS Northern Ireland Victim and Witness Survey

NSPCC National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children

PBNI Probation Board for Northern Ireland

PPS Public Prosecution Service

PSNI Police Service of Northern Ireland

RCSLT Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists

SAMM NI Support After Murder and Manslaughter Northern Ireland

SARC Sexual Assault Referral Centre

UU RPP University of Ulster Restorative Practices Programme

VSNI Victim Support NI

WAF Women's Aid Federation

WCU Witness Care Unit

Executive Summary

Background and Approach

1. The decision to conduct an inquiry into the criminal justice services available to victims and witnesses of crime in Northern Ireland was reached given the key role of witnesses, many of whom are also the victims of crime, in the criminal justice system and the intention of the Department of Justice to develop a new 5-year strategy for victims and witnesses of crime. As well as conducting an inquiry that would identify gaps in current provision, the Committee was determined that its inquiry would stimulate debate and engagement with the objective of influencing positive change and tangible outcomes in service provision for victims and witnesses by the criminal justice system.

2. During this inquiry the Committee has heard from and spoken directly to a wide range of advocacy and victims' representative groups and individuals and families who themselves have had first-hand experience of the criminal justice system. The Committee has also discussed the emerging issues with the Criminal Justice Agencies including the Department of Justice, the PSNI, the Public Prosecution Service, the Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunals Service and the Probation Board.

3. The Committee took account of existing relevant reports and research papers and commissioned research from Assembly Research Services on particular aspects of the services provided to victims and witnesses to inform its deliberations. Committee members undertook site visits during the course of the inquiry to a number of Northern Ireland's Courthouses to view the facilitates available to victims and witnesses and visited West Yorkshire Witness Care Unit to view the services that such Units currently provide in England and Wales.

4. The Committee is indebted to all those who participated in the inquiry through the provision of written and oral evidence and the hosting of visits and is also particularly appreciative of the invaluable contribution made by those individuals who agreed to take part in this process. The evidence provided by these individuals brought home to the Committee the very difficult experiences of those who, under very unfortunate and sad circumstances, found themselves gaining direct experience of the criminal justice system in Northern Ireland.

Current Position

5. The written and oral evidence received by the Committee has highlighted that a range of initiatives and work has been taken forward in recent years aimed at improving the services to and the experience of victims and witnesses who encounter the criminal justice system. These include the introduction of a Code of Practice for Victims of Crime, revised guidance on Achieving Best Evidence in Criminal Proceedings and the inclusion of additional provisions for the use of special measures for vulnerable and intimidated witnesses in the Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 2011. The Committee also heard examples of excellent service, often beyond what was required of them, being delivered by individuals within the system.

6. The Committee also recognises the crucial contribution made by Victim Support NI, the NSPCC Young Witness Service and other voluntary sector organisations in steering victims and witnesses through the system and providing support and assistance when it is most needed. The Committee commends the collaborative approach these organisations adopt with the statutory criminal justice agencies and believes that the system would be a much colder place for victims and witnesses without them.

7. However, despite all of this, victims and witnesses, and in particular bereaved families, still face significant difficulties with the criminal justice system and the criminal justice agencies and their experience of the process is often frustrating, demoralising and on occasions devastating as illustrated by comments such as "the trauma suffered by families can often be exacerbated by the criminal justice system" and "people are misinformed, ill-informed or not informed at all". The evidence from the victim support organisations has also illustrated the difficulties faced by victims and witnesses as has the findings of recent Criminal Justice Inspection reports.

8. There are a number of key issues that clearly impact upon victims and witnesses. These include: the lack of status victims and witnesses have within the criminal justice process; the lack of dignity and respect shown to victims and witnesses during the process; difficulty in understanding the process; difficulties in obtaining information about their case; feeling unprepared; the lack of support required to give evidence; the lack of emotional and psychological support services and practical assistance; the lack of a joined-up approach between criminal justice agencies; the lack of continuity of service within criminal justice agencies; poor facilities in courthouses; and the length of time cases take to reach a conclusion during which victims and victims' families lives are put on hold.

9. While these difficulties exist throughout the criminal justice process they are particularly acute in the PPS from the stage of the assessment of a case, through the process of a decision to prosecute, and on through to the completion of the case.

10. The co-operation of victims and witnesses in the criminal justice process is vital to achieving convictions and ensuring that justice is seen to be done. While recognising that the adversarial nature of the justice system does not provide a conducive environment for victims and witnesses it is the Committee's strong belief that much more can and needs to be done to redress the balance and ensure that an effective and appropriate service is provided for them. The Committee is therefore making a number of key recommendations to deliver the radical changes that in our view are required and the development of a new 5 year victims and witnesses strategy by the Department of Justice will provide the opportunity to take these forward.

The Status and Treatment of Victims and Witnesses

11. Issues around the status and treatment of victims and witnesses in the criminal justice system and the need for them to be treated with dignity and respect became a recurring theme during the inquiry. The evidence the Committee heard from individuals when outlining their experiences clearly demonstrates that engaging with the criminal justice system as a victim and/or witness or as a bereaved family is a daunting experience which can entail encounters with a number of criminal justice agencies and voluntary sector organisations from the time the crime is reported, through the police investigation, prosecution decision making process, court process, sentencing and beyond. It is the Committee's view that all victims and witnesses are entitled to be treated with dignity and respect by the criminal justice system and to be provided with the appropriate level of information in a timely manner.

12. Given the inability of the criminal justice organisations to achieve this to date the Committee does not believe that the introduction of further guidance documents will accomplish the 'step change' required. The Committee believes that entitlements for victims and witnesses must be put on a statutory basis and that these entitlements should be extended to bereaved families. The Committee also views mandatory training on the care and treatment of victims and witnesses as a necessity for all staff in criminal justice organisations who interact with victims and witnesses. Appropriate recommendations in these areas have been included in the report.

Single Point of Contact – Witness Care Units

13. There is general acknowledgement amongst the criminal justice agencies and the advocacy organisations who gave evidence to the Committee that Witness Care Units (WCUs) will be key in managing the early identification of vulnerable and intimidated witnesses, securing appropriate support services and ensuring that information is communicated more effectively to victims and witnesses thus improving the service provided.

14. The Committee supports the introduction of Witness Care Units, viewing them as an opportunity to provide a single point of contact for victims and witnesses in relation to their case to include co-ordination of support and services and the provision of timely information which should greatly improve their experience of the criminal justice system.

15. The Committee has made recommendations regarding the need for the remit of Witness Care Units in Northern Ireland to provide the single point of contact for as much of the process as possible and to ensure they are established as quickly as possible.

Communication and Information Provision

16. A major concern that recurred throughout the oral and written evidence was how the criminal justice organisations communicated with victims and witnesses, and the quality and timeliness of the information provided in individual cases.

17. While the criminal justice organisations outlined in their written and oral evidence the processes in place and the key stages when information should be communicated to victims and witnesses, the evidence from individuals, families and victim support groups indicated otherwise. The Committee heard many examples of failures in communications with victims and witnesses left feeling confused, frustrated, ill-informed or not informed at all. The manner of some of the written and verbal communication resulted in some feeling undervalued, side-lined and an 'inconvenience' to the process.

18. The Committee believes that improving the level of communication between the criminal justice organisations and victims and witnesses and the manner in which the communication takes place is central to improving victims' and witnesses' experience of the criminal justice system and their satisfaction with it.

19. The Committee has made a number of recommendations around defining communication procedures, clarifying entitlement to information and proactively providing information at key milestones throughout the process to victims and witnesses to assist their understanding of the criminal justice system in general and the position in relation to their case in particular.

Accountability

20. Due to the fragmented nature of accountability within the justice system there is much confusion around the level of service that victims and witnesses are entitled to and who has responsibility for the delivery of particular services or the provision of information at particular stages of the process. The Committee is of the view that there must be a requirement for each of the criminal justice organisations to account for the delivery of the services they are required to provide and have in place mechanisms to measure and report on performance against service standards with the aim of improving the service provided year on year.

21. The Committee has therefore made recommendations that provides for greater accountability for the provision of services to victims and witnesses of crime within each of the criminal justice organisations.

Support Provisions and Special Measures

22. The Committee believes that it is important that victims and witnesses of crime have access to a range of support services, including special measures, that provide practical assistance as well as emotional and psychological support and that these support mechanisms are in place for as long as they need them.

23. The Committee is concerned about a lack of consistency regarding the assessment for special measures, a lack of communication between the criminal justice organisations regarding individuals' needs and the absence of a formal review mechanism during the process to identify if/when an individual's needs change.

24. The Committee is also concerned that many individuals, particularly in relation to serious crime, did not feel they received the necessary practical support as their case progressed through the system or to deal with the impact of the crime and that the ability of organisations who could provide support was reduced by the current 'opt-in' system where individuals must consent to being approached by that organisation rather than having an 'opt-out' system.

25. To address the issues raised in relation to support provisions and special measures the Committee has made recommendations regarding early assessment and practical support interventions. The Committee also recommends obstacles preventing organisations from proactively approaching victims are removed, that examples of current best practice provisions are extended and that the issues regarding the specific needs of certain categories of victims are addressed.

Provisions at Court

26. It is clear from the Committee's visits to Londonderry, Lisburn and Laganside Courts and its discussion with individuals, that many of the court buildings in Northern Ireland are not conducive to the needs of victims and witnesses. Difficulties include lack of facilities, lack of privacy, proximity to the defendant and/or their supporters, and in some courts overcrowding due to the volume of business being conducted and the lack of a proper system for scheduling the timing of witness attendance.

27. While recognising that there is unlikely to be large amounts of capital funding available to deliver wholesale physical changes to courthouse layouts the Committee is of the view that improvements can be made to the facilities and rooms provided for victims and witnesses and the recently commissioned Review of the NI Courts Estate by the Minister of Justice provides an opportunity to do this. The Committee also believes that the scheduling of witnesses attendance could be much improved thereby reducing the length of time they are frequently required to wait and the pressure on facilities at busier courthouses.

28. The Committee has made recommendations to address the issues relating to the poor quality of the physical environment within courthouses and the standard of service provided to victims and witnesses when attending court including the introduction of a maximum waiting time for witnesses.

Delay in the Criminal Justice System

29. The Committee recognises the major impact delay in the system has on victims and witnesses and is of the view that avoidable delay between the incident occurring and the conclusion of the case must be tackled as a matter of urgency. The Committee believes that the Department of Justice needs to play a more important role in ensuring this issue is robustly tackled and it needs to be the focus of the highest level officials within each organisation to ensure it receives the necessary priority and response required.

30. While delay is a common complaint with regard to the entire criminal justice process the Committee found that one of the key frustrations for victims and witnesses is the length of time court cases take and the number of postponements/adjournments that often occur.

31. The Committee notes and supports the recommendation by the Criminal Justice Inspection that case management should be placed on a statutory footing and agrees with its analysis that this would be beneficial and have an overall positive effect in addressing delay and ultimately the experiences of victims and witnesses. The Committee is disappointed that the Department of Justice has declined to accept this recommendation and introduce a statutory case management scheme in the foreseeable future.

32. The Committee believes the issue of delay has been ongoing for much too long and substantive action, including the introduction of a statutory case management scheme is required now given the detrimental effect delay has on victims and witnesses.

Participation

33. As part of its consideration of victims' participation in the criminal justice process, the Committee considered evidence on Victim Impact Statements and Reports, Compensation, Youth Conferencing, and Restorative Justice.

34. The Committee is of the view that it is important that victims of serious crime and bereaved families have an opportunity to relate, during the criminal proceedings, the impact that the crime has had on them and for account to be taken of this impact and that Victim Impact Statements and Reports are appropriate mechanisms to achieve this. The current system however lacks clarity in relation to the completion, content and use of them. It is for these reasons that the Committee makes recommendations regarding the formal use of Victim Impact Statements and Reports.

35. The Committee also subscribes to the view that often the compensation process is the only form of participation in the criminal justice system for an individual affected by crime. It is therefore important that the compensation schemes in place are 'fit for purpose' and the operation of them is efficient and effective. The Committee has made recommendations to examine processes and procedures within the Compensation Agency and also review the underpinning legislation.

36. The Committee recognises that the adoption of restorative practices can be beneficial to victims of crime and can provide answers to questions that may otherwise go unanswered and therefore recommends that, when appropriate, the facilitation of restorative practices for those who wish to avail of this should be provided.

Collation of Information/Research on the Experiences of Victims and Witnesses

37. The Committee believes that the availability of detailed research and qualitative and quantitative information is a necessity to identify key issues that need to be addressed and inform policy development. The paucity of specific detailed statistical data and qualitative research across the criminal justice system is therefore an area that requires action. The Committee makes several recommendations regarding the collation of information on the experiences of victims of serious crime and the services provided to them by each of the organisations within the criminal justice system.

Conclusion

38. The Committee agrees with the view, as summed up in the words of one individual "I think that there is an imbalance of resources. The defendant has rights and that is how it should be. The defendant has a right to a fair trial and I am fully in favour of the rights of defendants but that should not entirely exclude some rights for victims and the families of victims. That is really important. It is not an either/or, it is a both" and believes it is now time to redress the balance.

39. The development of a new 5-year strategy for victims and witnesses provides an opportunity to make the substantial changes that are undoubtedly required within the criminal justice system. The implementation of the recommendations the Committee has made as part of this inquiry will ensure that the services provided to victims and witnesses and their experiences of the criminal justice system will be improved. The Committee expects the Minister of Justice to take full account of the findings and conclusions of this report in the new strategy.

Summary of Recommendations

The Status and Treatment of Victims and Witnesses

1. A Victim and Witness Charter providing statutory entitlements for victims and witnesses in terms of information provision and treatment should be introduced in the next available Justice Bill.

The Charter should, as a minimum, cover the following entitlements:

- Be treated with dignity and respect

- Receive information on the progress of their case and the reasons for any delay at identified key milestones in accordance with the timescales set out in the Code of Practice

- Be informed about the outcome of their case in accordance with the timescales set out in the Code of Practice

- Be given the reasons for the decision not to prosecute in accordance with the timescales set out in the Code of Practice

- Be provided with additional support if they are vulnerable or intimidated

- Receive information on the offender's release from custody and arrangements for their supervision in the community in accordance with the timescales set out in the Code of Practice

- Complain to an independent body if not satisfied with how an organisation has dealt with their concerns

2. Following on from this the Code of Practice for Victims and Witnesses should be revised to fully reflect these overarching commitments and set out clearly the key milestones at which information will be provided, the timescales for the provision of the information, how it will be provided and who has responsibility for its provision.

3. The same statutory rights should be afforded to bereaved families.

4. An independent complaints mechanism should be introduced to deal with all complaints that have not been satisfactorily dealt with through the internal complaints procedures of each organisation.

5. All staff in the criminal justice organisations who interact with victims and witnesses should receive mandatory training on the care and treatment of victims and witnesses.

Single Point of Contact – Witness Care Units

6. Witness Care Units in Northern Ireland should provide the single point of contact for as much of the process as possible and consideration should be given to how provision can be extended from before the point of a decision being taken to prosecute to beyond the conclusion of the court case to include appeal and post-conviction information and support.

7. Witness Care Units covering all the court regions should be established by December 2013.

Communication and Information Provision

8. Clearly defined communication procedures setting out the information that must be provided to victims and witnesses and the timescales within which it must be provided should be established for each criminal justice organisation. The communication procedures should build on the obligations in the Victims and Witnesses Charter and ensure:

- The key milestones in the criminal justice process at which information will be provided and the timescales for provision are clearly set out

- There is a proactive approach to the provision of information at each key milestone

- The information provided is tailored to the needs of the individual

- There is an opportunity for individuals to seek clarification/further information at any stage of the process

9. Victims should be entitled to receive a transcript of bail conditions including any variations set by the Court for offenders.

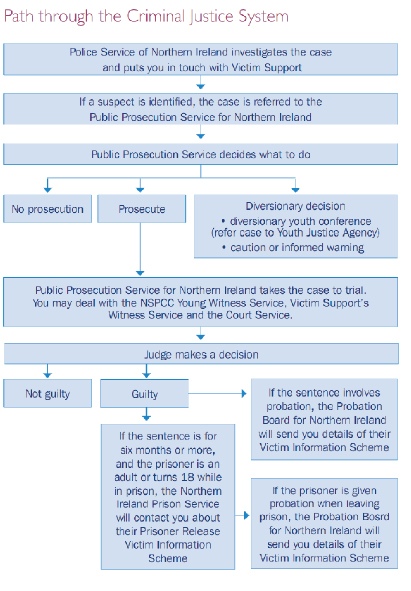

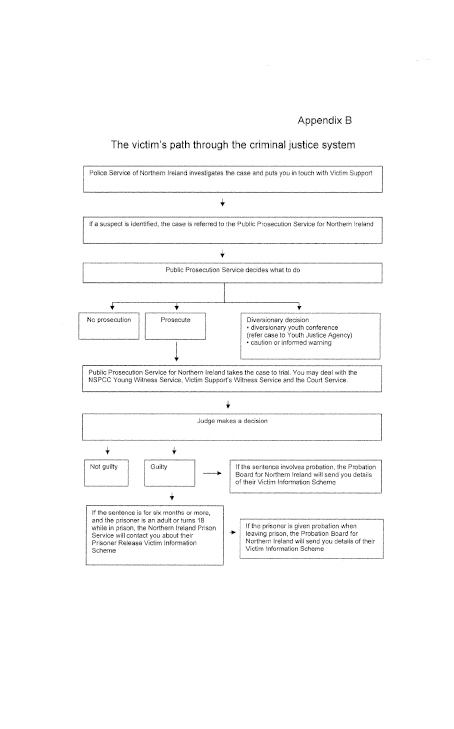

10. An easily understandable flowchart setting out case progression through the system and in particular all the various stages of a court case should automatically be provided to all victims and witnesses at an early stage in the process to assist understanding of the criminal justice system and identification of the various stages their particular case may go through.

Accountability

11. The Corporate and Business Plans for each of the criminal justice organisations should reflect their commitment to and actions for improving the services provided to victims and witnesses and should include an objective relating to victim and witness satisfaction levels.

12. Each criminal justice organisation should have measurable standards and mechanisms to monitor and assess delivery of services to victims and witnesses and satisfaction levels on an annual basis and the results should be published on their websites.

Support Provisions and Special Measures

13. A comprehensive formal assessment process should be introduced to identify the needs of individual victims and witnesses in relation to special measures and other support requirements at the earliest stage and the assessment revisited and revised as necessary as the case progresses. This is particularly important for victims and witnesses of serious crime.

14. In relation to serious crimes resources should be provided for practical support services including trauma counselling. These should be available from the crime occurs, throughout the process and beyond if necessary.

15. An opt-out system regarding being approached by Victim Support and the Probation Board should be developed to replace the current opt-in system.

16. Further research and analysis should be carried out to provide a clearer understanding of how avoidable attrition i.e. where a victim/witness withdraws or retracts their evidence, can be minimised and victims/witnesses better supported.

17. The Department of Justice should include actions to address the specific issues raised in relation to children and young people, victims and witnesses with communication needs, victims and witnesses who do not have English as their first language, victims of hate crime and victims of domestic abuse and sexual violence in either the new 5-year strategy for victims and witnesses or other appropriate means such as the proposed new strategy for tackling domestic and sexual violence and abuse.

18. The provision of remote live link facilities, based on the NSPCC Young Witness Service pilot model, and appropriately funded should be extended across Northern Ireland to provide victims and witnesses access to such facilities within a reasonable travelling distance.

Provisions at Court

19. An evaluation of the facilities currently provided for victims and witnesses in all courthouses should be carried out as part of the Courts Estate review with the objective of identifying specific improvements that can be made to provide comfortable and fit-for-purpose facilities within the current buildings for victims, witnesses and bereaved families.

20. The current management of facilities and services for victims and witnesses in courthouses should be examined and in particular whether the dependence upon volunteers is appropriate and properly funded and how a collaborative approach with the Witness Care Units can be developed.

21. A maximum waiting time for witnesses should be introduced.

22. Greater use should be made of specialist courts e.g. domestic violence courts and courts prioritising young persons' cases.

Delay in the Criminal Justice System

23. Case management should be placed on a statutory footing and this should be taken forward in the next available Justice Bill.

Participation

24. A formal system for the completion and use of Victim Impact Statements and Reports should be introduced as a matter of urgency and no later than the timescale proposed by the Department of Justice of January 2013.

25. There should be an automatic right for Victim Impact Statements to be completed in all cases involving serious crime.

26. A review of the legislation underpinning the compensation schemes should be undertaken to assess whether it is appropriate and adequate.

27. The issues highlighted in relation to operating procedures and processes should be addressed as part of the on-going Review of how the Compensation Agency delivers its services.

28. When appropriate, the option of participation in an appropriately conducted restorative practice should be facilitated for those victims who wish to avail of this.

Collation of Information/Research on the Experiences of Victims and Witnesses

29. An appropriate methodology for the collation of the experiences of victims of serious crime should be identified and implemented to include the experience of victims of domestic violence, sexual offences, hate crime and the nature and type of crime against children.

30. information on the experiences of victims and witnesses should be collated across each stage of the process to enable the services provided by the various criminal justice organisations to be assessed and particular issues identified and addressed where necessary.

Introduction

Background

1. On 23 June 2011 the Committee for Justice agreed to conduct an inquiry into the criminal justice services available to victims and witnesses of crime in Northern Ireland. This decision was reached given the key role of witnesses, many of whom are also the victims of crime, in the criminal justice system and the intention of the Department of Justice to develop a new 5-year strategy for victims and witnesses of crime.

2. In light of the Committee's decision, the Minister of Justice agreed that the Department would defer launching a consultation process on a draft strategy pending the outcome of the Committee's inquiry.

3. The Committee for Justice agreed the aims and terms of reference for the inquiry at its meeting on 29 September 2011.

Aim and Terms of Reference

4. The aim of the inquiry was 'to identify the outcomes that the Department of Justice's proposed new strategy for victims and witnesses of crime should deliver and make recommendations on the priorities and actions that need to be included in the plan to achieve these'.

5. The terms of reference for the inquiry was to:

- Review the effectiveness of the current approach and services provided by the criminal justice agencies[1] to victims and witnesses of crime;

- identify the key issues impacting on the experiences of victims and witnesses of crime of the criminal justice system and any gaps in the services provided;

- Identify and analyse alternative approaches and models of good practice in other jurisdictions in terms of policy interventions and programmes;

- Consider what priorities and actions need to be taken to improve the services provided to victims and witnesses of crime.

6. The Committee had initially intended to complete the inquiry by the end of February 2012. This timescale was however extended by three months to facilitate work that the Committee undertook in relation to a Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland which had to be completed by a deadline set in legislation, and also to enable it to fully explore a number of the issues that had arisen from the evidence and research gathered as part of the inquiry.

Committee Approach

7. The Committee agreed that the inquiry would include evidence based sessions with organisations working with victims and witnesses of crime and key criminal justice stakeholders and that it would seek written submissions and take account of existing relevant reports and research papers. The Committee also agreed to commission research from Assembly Research Services on particular aspects of the services provided to victims and witnesses to inform its deliberations.

8. The Committee placed a public notice in the Belfast Telegraph (Belfast and North West Edition), Irish News and News Letter on 7 October 2011 inviting written submissions and also wrote to key stakeholders seeking views. Eighteen written submissions were received from a range of organisations and these are included at Appendix 3.

9. Two oral evidence events were also held. The first of these took place in December 2011 in the Millennium Forum in Derry/Londonderry and considered evidence from advocacy/victims' representative organisations. At this event the Committee explored the emerging themes from the written submissions received and sought evidence on the measures and interventions required to improve the current system.

10. The second oral evidence event, held in January 2012 in the Lagan Valley Island Centre Lisburn, provided the Committee with the opportunity to explore directly with the PSNI, the PPS, the Compensation Agency, the Department of Justice, the Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunals Service and the Probation Board the issues raised by the advocacy and victims' representative groups and individuals with whom the Committee had met. The Minutes of Evidence of these events and other evidence sessions held are included at Appendix 2.

11. The Committee felt that it was extremely important to hear directly from victims and witnesses and their families to learn of the personal experiences of these individuals and agreed that it would meet with all victims and witnesses who made an approach to the Committee.

12. Five informal meetings with individual victims of crime and/or their families and an oral evidence session facilitated by Victim Support with the family of a murder victim and a victim of a serious crime were held. The Minutes of Evidence of the oral evidence session are included at Appendix 2 and a record of the informal meetings is included at Appendix 6.

13. The Committee was also interested in viewing the facilitates available to victims and witnesses in Northern Ireland Courts and undertook visits to Lisburn, Londonderry and Laganside Courthouses.

14. Following the announcement of the Minister of Justice of his intention to establish Witness Care Units (WCU) in Northern Ireland, the Committee undertook a visit to West Yorkshire Witness Care Unit to view the services and facilities that such a unit could provide. A report of the visit is included at Appendix 6.

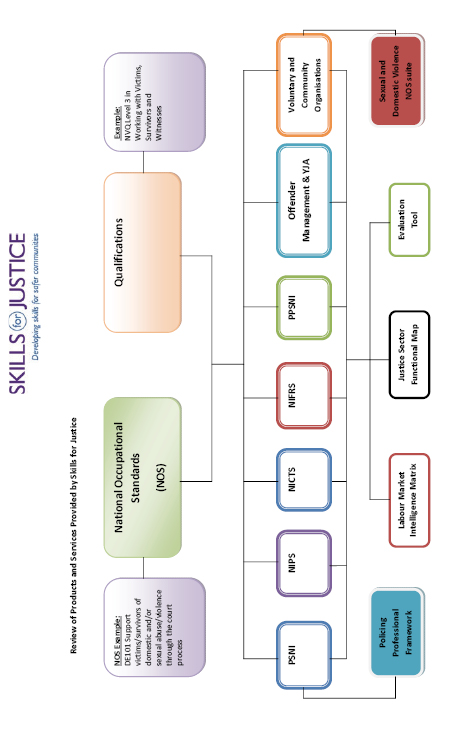

15. The Committee commissioned a series of research papers on the role of the victim in the criminal justice system and the pathway experienced by victims, examples of good practice initiatives improving the experiences of victims and witnesses, the statutory requirements of criminal justice agencies in Northern Ireland in respect of victims and witnesses, and victim impact statements to assist its consideration of emerging themes and issues. The research papers are included at Appendix 4.

16. The Committee also participated in and attended a number of relevant events and conferences relating to the experiences of victims and witnesses, including the joint NSPCC NI and Victim Support NI Seminar 'Victims' Voices: Experiences of Children and adults of the Criminal Justice System in Northern Ireland' in November 2011 and the CJI Conference in January 2012 on 'The future of victim and witness care: from aspiration to reality'.

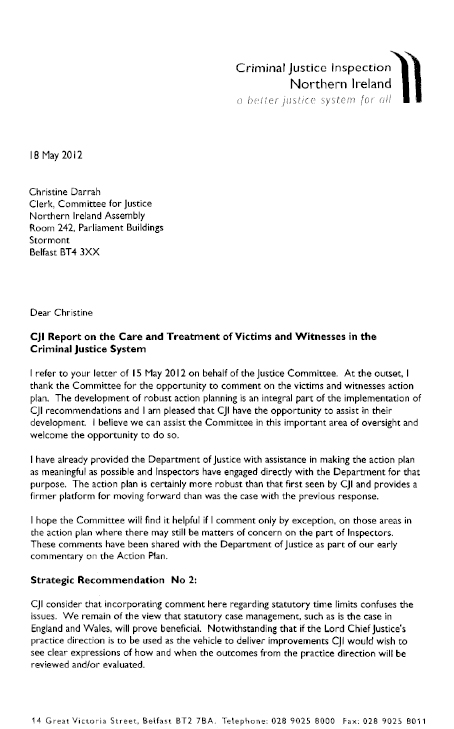

17. During the inquiry the Criminal Justice Inspectorate published a number of relevant reports including 'The care and treatment of victims and witnesses in the criminal justice system in Northern Ireland',[2] 'The use of special measures in the criminal justice system in Northern Ireland',[3] and 'Telling Them Why – An Inspection of the Public Prosecution Service for Northern Ireland's giving of reasons for its decisions.'[4] The Committee has considered the findings of these reports when formulating its conclusions and recommendations.

Acknowledgements

18. The Committee wishes to record its thanks to all those who participated in the inquiry through the provision of written and oral evidence and the hosting of visits, and in the case of Victim Support NI, facilitating the Committee's interaction with a number of individuals. In particular the Committee wishes to formally acknowledge the invaluable contribution made by those individuals who agreed to take part in this process. The evidence received, whilst at times distressing, brought home to the Committee the very difficult experiences of those who, under very unfortunate and sad circumstances found themselves gaining direct experience of the criminal justice system in Northern Ireland.

Consideration of Evidence

The Status and Treatment of Victims and Witnesses

19. Issues around the status and treatment of victims and witnesses in the criminal justice system and the need for them to be treated with dignity and respect became a recurring theme in the evidence the Committee heard from individuals when outlining their experiences. Victims and families described how they felt like a 'by-product', 'that the business and interests of the court centre on the perpetrator and the needs of the court not the victim', and that they were not treated on an equal basis with defendants, particularly in relation to access to information. One individual described how she felt that she was not initially treated as a victim - 'I felt like I wasn't the victim until it was proved I was, rather than a victim until they proved I was not'. SAMM NI told the Committee that unless a family member is being called as a witness the family has no role in the system. Families are told repeatedly that they are not victims as the victim is dead.

20. An individual in written evidence stated 'The main message I would like to get across is for more understanding of what victims are going through and the impact of actions and words from the authorities . . . What I think needs changed is that victims need to be seen as humans with real feelings and emotions. The best thing that could change is attitudes towards victims'. The same individual went on to state that while she would not discourage others from reporting a crime, her experience of the system would prevent her from doing so.

21. The Committee met a number of families of victims of crime who were made to feel they had no rights or entitlements particularly with regard to the provision of information. One family described being told that they didn't need to know particular information, that they would not understand, did not need to be present in court at particular stages and that 'barristers do not talk to families'.

22. Another individual, in his evidence to the Committee, described his perception that there is unbalanced treatment of victims and defendants. In his experience of participating in the youth conferencing process as a parent on behalf of his son who was the victim he stated that he had no automatic entitlement to the conference report, even though these are provided to the offenders and that this is also the case in relation to copies of statements - victims do not receive copies of statements made by the accused in advance of court proceedings, yet the defendants receive copies of all statements made by victims and witnesses. He also pointed out that at the youth conference there were five people present representing the interests of the defendant's side including the defendant, a solicitor, a youth worker and a parent, while he alone took part as the representative of the victim.

23. Another family member of a murder victim said 'Everything centres on the perpetrators. Perpetrators will have a team of funded agencies advising and representing them; they will be told what will happen to them, when it will happen, what support is available to them. There will be a range of booklets/handouts and online information sites for them to refer to. This is not the case for victims.'

24. Many of the individuals who gave evidence to the Committee stated that they did not want better treatment than the defendant but wanted some parity. This is summed up in the words of one individual - 'I think that there is an imbalance of resources. The defendant has rights, and that is how it should be. The defendant has a right to a fair trial, and I am fully in favour of the rights of defendants, but that should not entirely exclude some rights for victims and the families of victims. That is really important. It is not an either/or, it is a both.'

25. Women's Aid highlighted that one of the key issues consistently raised by women using its services is the position, status and dignity of the victim in the overall process. Often they feel subsumed by the criminal justice system, rather than being an active participant. This is frequently compounded by the lack of timely and accurate information and feedback being supplied to them.

26. Women's Aid stated its belief that the care and support of victims and witnesses of crime must be a central component of the criminal justice system in Northern Ireland. Victims must be afforded the dignity and respect they deserve and should be accorded fundamental rights which allow them to progress through the system in a manner which avoids compounding the trauma they have already experienced and enhances their ability to give best evidence. Women's Aid contends that there is considerable merit in formally and legally recognising the status of the victim in criminal proceedings and ensuring that specific rights and entitlements follow from this.

27. In written evidence the University of Ulster Restorative Practices Programmes (UU RPP) indicated that the current criminal justice system in Northern Ireland needs to be rebalanced to focus on the needs and interests of the victim as well as those of the offender and communities. As throughout the process victims have little or no part to play, their voices are seldom heard and their needs and interests are rarely addressed effectively. The UU RPP stated that Northern Ireland needs a comprehensive policy on victims of crime and an effective strategy for implementation to rebalance the criminal justice system. This does not imply the needs and interests of offenders should be neglected. It is UU RPP's submission that the recent EU Directive on Victims of Crime provides a structure for such a policy which should be subject to independent research and evaluation.

28. Victim Support NI believes there needs to be a behavioural change within the system as a whole, with organisations demonstrating more emotional intelligence in their interactions with victims and witnesses, highlighting that one of the key issues consistently raised is the position, status and dignity of the victim in the overall process.

29. From Victim Support's experience, treating victims with dignity and respect is the responsibility of every individual providing a service within the criminal justice system. Furthermore, Victim Support believes treating victims and witnesses with dignity and respect should be integral to the ethos and behaviours of every criminal justice organisation.

30. Victim Support states that the changes needed to the criminal justice system will not be fixed solely by the introduction of more policies and procedures. It is the individual interaction with victims and witnesses that make the difference and this will take more of a behavioural change within organisations as a whole. The underlying motivations of all the agencies of the criminal justice system should be to provide victims and witnesses with appropriate support in order for them to give their best evidence.

31. Victim Support believes that each organisation should be committed to causing no further harm to individuals affected by crime. This should become integral to their core business and be demonstrated through its inclusion in their strategic and business plans and through their leadership. Overall however the benefit will be achieved not from 'add on' policies and procedures but through a change in attitude, demonstrated through behaviour.

32. In its written submission NSPCC states that children who are victims or witnesses of abuse require a system which treats them with respect and is sensitive to their needs. A system which is insensitive runs the risk of causing further trauma to victims, impacting on their recovery and damaging their confidence in the criminal justice system as a whole as well as their ability to access justice.

33. SAMM NI in its evidence, identified what it describes as a serious flaw in the current approach, namely that all criminal justice agencies refer to the needs of victims and witnesses in their strategies, but there is no reference to the needs of families bereaved by murder and manslaughter. SAMM NI recommends that the needs of families should be acknowledged by all agencies they come in contact with during the investigation and court experience.

34. In its written submission the NI Policing Board stated that after a criminal offence has been committed, the victim's first contact with the criminal justice system is normally with the police. That contact will likely continue through the judicial process. The police response to the report of a criminal offence will therefore have a direct and often decisive impact on the victim's attitude to the criminal justice system and it is critical that the police treat all victims with compassion and respect for their dignity. They must ensure that the victim feels that the offence is being considered properly and is being taken seriously. Victims often feel a sense of frustration, fear and insecurity but police officers can make a real difference to a victim's experience as they progress through the system. Respect, compassion and understanding for victims should be the hallmark of police conduct.

35. The PSNI stated that it is committed to ensuring it provides a high standard of service to the victims and witnesses of crime and that this can be evidenced in its recently introduced 'Policing Commitments' which outline the minimum standard of service members of the public, including victims of crime, can expect from its officers and staff. One of the PSNI's key commitments is to ensure that members of the public are treated with dignity and respect.

36. The PSNI acknowledges and endorses the requirement to continually review the training needs of those officers and staff who interface with victims and witnesses on a daily basis and is currently working on a training package for all frontline officers.

37. In its written submission the PPS stated that there is now an increased awareness across society of the impact of crime upon the victim and also of the impact for victims of engaging with the criminal justice system. The PPS recognises the traumatic experience that the undeserved and unwanted involvement in a crime can bring for many people. Equally important is the increased realisation that how the victim is dealt with by the criminal justice system can have a profound effect on how that person can cope with the experience of crime.

38. The PPS went on to state that it recognises that there may be a perception among victims that there is no one to 'represent' them, while the accused is perceived to be fully represented. PPS notes the outcome of recent research which demonstrates that the key issues impacting upon victims and witnesses experiences of the criminal justice system can be summarised by a desire to be treated with sensitivity and respect, and to be provided with information about their case and the process. Whilst highlighting that some victim and witness dissatisfaction derives from the way in which the adversarial system operates the PPS indicated that there remained a necessity to address these key issues. It did however highlight the need to consider proportionality and the availability of resources.

39. The PPS stated that a simple explanation of minimum service provision for victims is set out in the interagency publication the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime.

Single Point of Contact - Witness Care Units

40. There is general acknowledgement amongst the criminal justice agencies and the advocacy organisations who gave evidence to the Committee that Witness Care Units (WCUs) will be key in managing the early identification of vulnerable and intimidated witnesses, securing appropriate support services and ensuring that information is communicated more effectively to victims and witnesses thus improving the service provided.

41. The 'one stop shop' initiative was recommended by CJI in its 2005 thematic inspection report 'Improving the Provision of Care for Victims and Witnesses within the Criminal Justice System'[5]. That report recommended that the Criminal Justice Board should set up a jointly owned victims and witness information unit which would act as a single point of contact to the criminal justice system to assist victims and witnesses with information on progress of cases and referrals to bodies for specialised support. The CJI report pointed to WCUs in England and Wales as models for consideration.

42. In its most recent report on the care and treatment of victims and witnesses, published in December 2011, CJI expressed disappointment that, despite the recommendation being accepted and included in strategic action plans to implement the report recommendations, the initiative had not been progressed.

43. CJI has again recommended the establishment of 'one-stop-shops' for Northern Ireland in the form of WCUs led by the PPS and using the existing Community Liaison Teams as the core basis for delivery. Inspectors outlined that in their view 'an amalgam of PPS CLTs, elements of the PSNI R4model (in terms of victim contact and updating), NICTS CPOs and VSNI can provide a vehicle to achieve a WCU ('one stop shop') facility which will significantly enhance the experience of victims and witnesses.'

44. Following the publication of the report the Minister of Justice accepted the recommendation and stated that work in relation to the establishment of WCUs would be taken forward.

45. In its written and oral evidence the PPS confirmed it is the lead organisation for the introduction of a WCU model for victims and witnesses in Northern Ireland. The PPS outlined that work has been undertaken with the PSNI which has identified a number of good practices which can be imported from elsewhere.

46. The PPS stated that it is anxious to ensure that the introduction of WCUs leads to substantive, positive change in the level of service offered to victims and witnesses and there may be opportunities to provide a higher level of service here than is currently available in England and Wales. For example, the Causeway system would enable a WCU in Northern Ireland to deal with a case from an earlier stage and to a later stage than is possible in England, where such an integrated IT system is not presently available. In Northern Ireland the witness care officer, could, in due course, provide information in relation to matters such as the details of custodial sentences, release dates etc. enabled through partnership working with the Probation Service and the Prison Service. A further development of this model may be to have a dedicated witness case officer for the WCU at court to facilitate the coordination and handling of witness care issues in a holistic manner. This would build upon the existing working relationships with Victim Support and the NSPCC.

47. In its submission the PSNI strongly advocates the establishment of WCUs within Northern Ireland as a means of delivering an appropriate, seamless, efficient and effective service to victims and witnesses across the Crown, Magistrates and Youth Courts. The PSNI described the scoping work it has already carried out regarding the establishment of WCUs which includes identifying possible unit locations, business models, process and procedures. As a result the PSNI recognises the success of such units are heavily dependent upon the joint development, staffing and management with the PPS.

48. The Probation Board for Northern Ireland (PBNI) is of the view that a singular interface for victims is the most effective means of providing accurate, timely information about the criminal justice system. PBNI states that, in real terms, this means the amalgamation of existing Victim Information Schemes and bringing into a singular entity the provision of support services for witnesses.

49. The PBNI also states that an integrated service for victims after an offender has been convicted could lead to the development of appropriate technology to exchange information with victims and witnesses, and also provide a single point of contact for more general information (helping to raise awareness and thus confidence).

50. The PBNI highlights that information provided to victims post-conviction may be more effectively delivered on an 'opt out' basis (rather than the current 'opt in' requirement). That is, unless otherwise specified, victims will receive information about the sentence given to an offender and their progress.

51. The written submission from the Office of the Lord Chief Justice states that the judiciary would welcome the establishment of WCUs as it considers that such Units would significantly improve the experiences of witnesses through the system. It should also improve the level and consistency of contact which the PPS/PSNI have with a victim, and this will ensure that accurate information about witnesses needs and their availability will be before the court at the earliest possible opportunity.

52. Both Victim Support and Women's Aid state that whilst recognising the importance for agencies to have autonomy and independence a victim or witness trying to navigate their way through this system can find it extremely difficult and complex.

53. Victim Support believes victims should be afforded better support and information from their initial contact with the system to when this ends. Part of this end to end support should also be the establishment of WCUs to both assess need and provide information to those attending any criminal trial before, during and after hearings.

54. In its submission SAMM NI provided examples of the day-to-day financial and practical problems facing families who have suffered a bereavement and invited the Committee to study international best practice in the provision of liaison officers who act as 'gatekeepers' for families.

55. Much of the evidence heard from the individuals who gave evidence to the Committee describes the frustration of victims, witnesses and their families regarding their inability to gain access to information, services and support. Many felt their lack of understanding and experience of the criminal justice system was a barrier to their effective participation in the process.

56. In written evidence one victim of crime stated that 'a great difference in all of this would have been more support. I was left alone with no contact or someone to explain things to me. I had to arrange my own counselling to get any support at all.'

57. In an oral evidence session with individuals facilitated by Victim Support, one family stated there was a need for liaison for families and there was an absolute gap in provision. In their own words – 'Overall, we thought that what would improve the system would be a dedicated liaison officer: someone who would act on behalf of the family . . . we think that we need someone who has access to all parts of the process, including the agencies, and who has a right to ask for updates.'

58. The family also stated that the only way they could ensure that they were kept up to date with progress in relation to the court case was to attend every single mention in the Magistrate's Court. 'Every time we went to court, they told us when the next court date would be and whether it was a mention or a trial date or whatever. Other than that, no one told us.' They went on to say 'You need someone there to fill you in on what is happening — not necessarily on the details of the case, because there is a lot of confidentiality — why it is happening, and what the process is, and to support you in that way.'

59. The family described how they had to seek out and form relationships with officials from the various agencies as their case progressed through the system in order to gain access to information. Now that the court case concerning their relative was over, they understood that an appeal had been lodged in respect of the case and again they had no information on the appeal or the process.

60. To view at first-hand the types of facilities and services available to witnesses, and to explore areas that could be built upon to offer an enhanced service to victims and witnesses of crime in Northern Ireland in March 2012 the Committee undertook a visit to the West Yorkshire Witness Care Unit based in Bradford.

61. The visit provided the opportunity to meet with the key leads from each of the criminal justice agencies to discuss the strategic management and operation of the WCU. Committee Members also met with Unit Managers to discuss the practicalities of managing a multi-agency Unit and availed of the opportunity to gain actual experience of the service provided to witnesses by spending some time with on-duty witness care unit officers as they carried out their duties.

Communication and Information Provision

62. The evidence received from advocacy groups and individuals clearly indicates that one of the key issues facing victims and witnesses is in obtaining timely and regular information in relation to their individual case. A family member of a victim stated – 'It is this business of the communication gap. You need reassurance and to know the details. You need to be kept informed if you want to be informed. I imagine that some people do not want to know but most people would probably want to know. You have a right to that. You are a key person in the trial: either you are the victim or the family of the victim. It is important that the system includes you.'

63. The Committee heard evidence that victims and witnesses find the criminal justice system confusing and complex and are not receiving clear, concise and timely information at each key stage of the process. The quality and detail of the information that is provided, and access to this information, is inconsistent and adhoc across the system and within each of the criminal justice organisations and there is a lack of clear demarcation of responsibility for communicating particular information.

64. The lack of a pro-active approach to communicating information by the criminal justice agencies was repeatedly highlighted. In the words of one individual 'throughout the 2 years of the legal process I constantly found myself having to chase information'. Not being kept up-to-date with case progression was a criticism levelled at the PPS in particular. The Committee were given examples such as one individual not being informed of a 'decision to prosecute', and another having to wait eight months 'to be told there wasn't enough evidence for reasons I found unfair, in a cold patronising letter'.

65. Other individuals who spoke to the Committee said they were not informed of court dates, including bail hearing dates. This resulted in two of the individuals who spoke to the Committee having no information about the bail conditions attached to the defendants involved in their cases. Another family described attending every court hearing as their only means of ensuring they were kept informed of what was going to happen next. Yet another family referred to a further breakdown in communication regarding a particular court date when the defendant in the case pleaded guilty. The family had no prior indication of this possibility and consequently a number of family members (who would have wished to be present) were absent from court. The family described the very devastating effect this had on them.

66. Many of the individuals who spoke to the Committee felt they had no rights or entitlement to the information they wanted and that information gained was on a 'favour basis' by forging their own contacts within each of the criminal justice organisations – 'lack of communication was the biggest issue with which we had a problem. Nobody told us anything. We tried really hard to build bridges and to make contacts in order to get an answer from anybody.'

67. One family described in an informal meeting with the Committee, their experience of a lack of pro-active communication throughout the process and wished to emphasise that families need to be kept updated on a regular basis even if nothing is happening. The family stated: "People are misinformed, ill-informed or not informed at all' and went on to highlight the need for verbal information to be followed up with written information as people often do not pick up properly what is being said when they are traumatised.

68. Other difficulties faced included:

- A lack of knowledge and understanding of the criminal justice process which resulted in key milestones in the process passing without their awareness, eg the 28-day limit within which an appeal on grounds of leniency in relation to a sentence must be made.

- Having to deal with a lack of knowledge in relation to their individual case by the criminal justice organisations themselves. Examples of this was the gaps in knowledge caused by police investigation officers changing during the course of one case and the Family Liaison Officer changing in another. Also different prosecutors dealing with the case as it progressed through the court system. The resulting inconsistency in approach and the requirement on the part of the victim and/or their families to retell their story on a number of occasions was difficult for those involved.

69. Proposals by individuals who have experienced the system to improve communication include the provision of a dedicated liaison officer — someone who would act on behalf of the family, has access to all parts of the process, including the agencies, and who has a right to ask for updates; the provision of a simple and easy to understand flowchart explaining case progression through the criminal justice system and in particular case progression through court; the introduction of a policy to ensure victims receive a transcript of any bail conditions set by the Court for offenders; and that access to information should be provided on an equal footing to both defendants and victims including copies of statements made by the accused in advance of any court proceedings.

70. From its research and work with victims, Victim Support NI has identified the provision of timely and appropriate information as one of the things victims most want from the criminal justice system. In its submission Victim Support stated that very often individuals become increasingly frustrated and despondent when more and more time passes with no contact or information from the relevant criminal justice agency. A lack of information can often make victims feel that their case is not being taken seriously when often the opposite is the reality.

71. In their written submissions both Women's Aid and Victim Support recommended that all communication with victims of crime should be done in a way which is personable and tailored to the individual's level of literacy, language and capacity to understand and that individuals should be afforded the opportunity to ask for clarification and receive this clarification in a reasonable amount of time. Women's Aid also recommended the establishment of clear and concise communications protocols within the criminal justice system defining whose responsibility it is to communicate important information and decisions to the victim.

72. The Law Society in written evidence advocated the importance of victims being kept informed throughout the process of investigating and prosecuting a case. The Society highlighted the complexity in relation to prosecutorial decisions and the range of subsequent sentencing options and suggests that more could be done to ensure the victim and/or their family fully understand the decision making process and the purpose of non-custodial sentences in particular.

73. In oral evidence the Northern Ireland Council for Ethnic Minorities (NICEM) also highlighted lack of clarity regarding responsibility for advising victims and/or their families regarding sentencing and the opportunity to appeal and the time constraints involved. NICEM used the example of a case of racial murder for which sentencing took place just before the Christmas holiday period and lack of knowledge regarding the time limitation led to an appeal application being prepared in just four days. NICEM recommended a mandatory requirement that victims be informed of their rights if they feel that sentencing is too lenient.

74. In its submission the UU RPP emphasised the adverse effect on victims not being kept informed about progress on detecting and prosecuting their case and recommended that victims should be routinely updated by the PSNI or the PPS on case progress and given a contact point which they can use proactively.

75. The UU RPP also highlighted that some victims do not understand how sentences are determined in their cases, are excluded from the 'deals' that are negotiated between the prosecution and defence over charges, pleas and anticipated sentences and have no access to pre-sentence reports. The UU RPP recommended that a victim advocate should be available to explain to victims the sentencing process, inform them of the key issues being addressed in the process and represent victims' views and interests.

76. It went on to state that victims may wonder about what effects the sentence has had on the offender and highlights that victims have a strong interest in not only their own safety but also in the protection of other potential victims. The UU RPP expressed the view that those agencies responsible for the implementation of court sentences should provide a report at the completion of the sentence on the offender's participation in the sentence and its outcome in relation to the reduction of risk in reoffending and that, towards the completion of custodial sentences in the cases of serious violent or sexual offences, victims should be informed about the arrangements for release and risk management in relation to the offender and kept informed on any breaches of changes in these arrangements.

77. Women's Aid is of the view that there can be an assumption that a victim and/or witness is able to recognise and understand the key components of the criminal justice system and that this is not always the case. Women's Aid has provided support to women, who have not understood the basic roles and functions of the PPS and have been confused by the use of legal terminologies and the failure to fully and clearly explain decisions. In oral evidence Women's Aid stated that victims are often not informed of, or aware of, bail conditions or the serving of non-molestation orders.

78. This was reiterated by the parent of a victim who advised the Committee that the family were not advised of a bail hearing and was therefore not present in court to hear bail conditions. They were subsequently advised that information could not be released to them on the bail conditions even though these were read out in public session and would be released in response to a media enquiry.

79. In oral evidence SAMM NI stated that the information that bereaved families get is very patchy particularly during the period when the case goes to the PPS. SAMM NI also went on to highlight the lack of information about the appeal process as there is no mechanism for informing families directly that an appeal has been lodged.

80. The PSNI stated in its submission that it is continually working to improve communications with victims with a view to ensuring such contact is consistent, both in terms of quality and frequency. A recently introduced programme to improve the victim update process ensures victim updates are 'flagged' at 10 days, 30 days and 75 days. The programme is audited for compliance and quality. The new victim update process also ensures victims are informed when a case cannot be 'taken any further'. It also described other methods of information provision to victims including ensuring victims are aware of the support services available to them and the provision of support and communication through the use of Family Liaison Officers in cases of murder, manslaughter, road death and other serious crime.

81. The PSNI stated that it recognises the negative impact of inconsistencies in service provision across the justice system on victims and witnesses in relation to communication and plans to work in cooperation with the PPS to ensure written communications carry consistent messages.

82. The PPS stated that it recognises the importance of information provision and is committed to ensuring that victims are kept informed of case progress. Within its written submission and in oral evidence to the Committee the PPS identified the key stages when it provides written communication to victims and/or their families, ie at the time of charge in cases of death; on receipt of case file from police in indictable cases; when a decision whether or not to prosecute is made (with explanation in particular cases); court attendance dates and case outcome and the type and level of information covered.

83. It emphasised that in giving reasons, a balance must be struck between the proper interests of the victim and other concerns, such as damage to the reputation or other injustice to an individual, the danger of infringing upon the presumption of innocence or other human rights and the risk of jeopardising the safety of individuals.

84. The PPS advised that a review of its correspondence to victims and witnesses has almost concluded and has involved consultation with key stakeholders from the voluntary sector. It is also currently examining the circumstances in which the reasons for no prosecution decisions can be given in an increased range of cases.

85. During the oral evidence session with the criminal justice organisations, the Committee questioned PPS officials on the rationale for using Police Family Liaison Officers to communicate prosecutorial decisions to families in cases involving a death, and questioned whether it would be more appropriate for Police Family Liaison Officers to be accompanied by a PPS representative. In response the PPS officials explained that the decision to use Police Family Liaison Officer's in this way was because of the relationships these officers establish with bereaved families. The PPS confirmed it follows up the Police Family Liaison Officers contact with a letter containing further information and providing a point of contact for the family and that in every serious case PPS offers a meeting to explain decisions of no prosecution.

86. The PPS described the establishment of Community Liaison Teams (CLTs) as the most demonstrable change in service provision since the setting up of the PPS. These CLTs are dedicated to providing information to victims and witnesses and were developed to meet the need for victim and witness liaison in the Magistrates' and County Courts. The principal functions of CLTs are to check witness availability; send out documentation regarding attendance at court, including the services offered by Victim Support Witness Service; and answer general queries a witness may have.

87. There are however limitations as PPS has not been resourced to deliver CLT services in the Crown Court where police retain a significant role in witness liaison and whilst current arrangements provide for witness attendance at court, they do not extend to the delivery of services at court or to providing assistance at the post court stage. The PPS identified that a potential further development in CLT service provision could involve the establishment of a PPS dedicated support officer to carry out a meet and greet role at court and to deal with witness queries which arise there.

88. The PPS also acknowledged that it does not have a system at the moment for informing every single victim of every single court hearing, but is introducing a victim information portal (an online information system) designed to do exactly that for people who want to be told about every single hearing in a case.

89. In its written submission the Probation Board for Northern Ireland (PBNI) explained how it currently engages with victims of crime through the provision of its statutory Victim Information Scheme and the preparation of reports for the Parole Commissioners in relation to life sentence cases which enables the victims' families to have their say regarding concerns they may have on a prisoner's release under PBNI supervision.

90. PBNI stated that the way in which the criminal justice system engages with victims of crime needs to change. PBNI highlighted the common concerns it hears from victims about lack of timely information, lack of on-going contact and confusion about entitlement to accessing information. In its submission PBNI advocated for a single interface for victims, i.e. the amalgamation of existing Victim Information Schemes.

91. PBNI believes that it is well placed and wishes to play its part in the provision of services to victims including providing victims with specific and tailored information about their particular case. PBNI stated that it wishes to be part of an integrated service to victims which operates on an 'opt-out' rather than 'opt-in' basis as currently victims must pro-actively register with PBNI's Victim Information Scheme in order to receive its services. PBNI are concerned that the current system is unwieldy, adds unnecessary delay and prevents PBNI from providing timely and accurate notification to victims.

Collation of Information/ Research on the Experiences of Victims and Witnesses

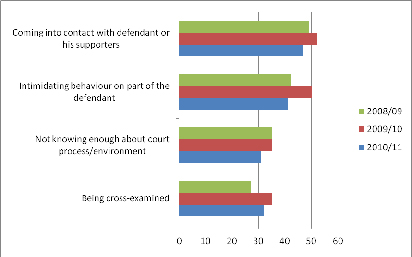

92. The Committee heard evidence from a number of the advocacy groups that detailed research and information on the experiences of victims and witnesses, particularly in relation to serious crimes, is not readily available. The information that is collated does not identify the level of service provided by each of the criminal justice organisations at the different stages of the process or enable specific issues relating to a particular organisation to be identified to enable appropriate action to be taken. There is also a lack of detailed research and information on the reasons for, and levels of unreported crime, why cases do not proceed, and patterns of crime against particular groups.

93. In its written submission the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) stated that the collation of information crucial for policy development in relation to child victims is not currently available. At present official statistics are not able to identify the reasons why cases do not proceed and the differential impact this has on various groups of victims. Additionally, essential information on the nature and type of crime against children and young people remains unknown in the vast majority of cases. The NSPCC also highlighted that although the Northern Ireland Victim and Witness Survey (NIVWS) provides a detailed overview of experiences of crime within NI, it currently does not routinely include under 18's, nor does it address violent or sexual offences.

94. The NSPCC recommended that current information management systems should be developed to allow for the recording of alleged offender details in undetected cases to facilitate better understanding of the nature of crime against children; better use of current criminal justice system information management systems is needed to inform key strategies and to monitor levels and patterns of crime against children as well as case outcomes; and the introduction of mechanisms to gather information from child victims about their experiences of the criminal justice system is required. This should take particular account of vulnerable groups such as those who have been the victims of sexual crime, disabled victims and those who have been subject to violent crime perpetrated by parents/caregivers.