Brexit & Beyond newsletter

9 May 2023

Welcome to the 9 May 2023 Brexit & Beyond newsletter

Welcome to the 9 May 2023 Brexit & Beyond newsletter

Last week, legal, academic and trade experts gave evidence on the Windsor Framework to the Lords Sub-Committee on the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland. The UK in a Changing Europe think tank has published its latest tracker of EU-UK divergence. Horizon Europe was discussed in the Commons, amid concerns from scientists and researchers that the UK has not secured associate membership to the EU scheme.

Legal, academic and trade experts on the Windsor Framework

On 3 May, legal, academic and trade experts gave evidence on the Windsor Framework to the Lords Sub-Committee on the Protocol. Dr Lisa Claire Whitten, a Research Fellow at Queen’s University Belfast, who works on QUB’s Post-Brexit governance project, echoed previous witnesses in saying that it is positive there is a joint EU-UK solution. She highlighted the new mechanisms in the Framework to address future problems, and said the discrepancies in the UK’s and EU’s language on the Framework are not in the legal texts. On the other hand, Martin Howe KC said that it’s hard to see the Windsor Framework as positive compared to the baseline grace periods. He stated that there clearly remains “quite a strict border” between GB and NI. He argued that some statements in the UK Government’s command paper are at a minimum “highly misleading and questionable”. Dr Anna Jerzewska, a customs and trade expert, said for the private sector, the biggest issue is uncertainty, so from that perspective the Framework is great. However, she noted that it doesn’t remove customs formalities, even for goods which remain in NI.

Customs and trade expert Anna Jerzewska | Source: UK Parliament

The Stormont Brake

Howe called the new Stormont Brake mechanism (which allows 30 MLAs to stop the application of certain EU laws, under certain conditions) “a very poor brake in theory and most unlikely to be of any practical effect”. Whitten emphasised that it is innovative: for the EU it provides “a small group of elected representatives in a sub-state polity and a third country the capacity to initiate a brake on the evolution of EU legislation” and for the UK, it gives MLAs “an avenue for decisive effect on a formerly reserved area of UK-EU relations”. However, there is a high threshold for notification, and consultation provisions, and she said is designed to be mechanism of last resort. Whitten suggested that its use could be considered a failure of the other provisions. Whitten noted that the new provisions may strain the capacity of NI Assembly officials and politicians: the work of NI Democratic Scrutiny Committee could be considerable, depending on MLAs’ interest, and the timelines are unforgiving. The EU law which is in scope of the new mechanisms includes legislation which falls outside NI’s devolved competence, and so MLAs and officials may be required to monitor areas of EU policy which they have never been directly responsible for. Whitten also highlighted the Brake’s possible interaction with Article 2 of the Protocol on individual rights: some laws underpinning this UK Government commitment (to ensure “no diminution of rights, safeguards and equality of opportunity” in NI post-Brexit) are in scope of the Brake, and so hypothetically there could be a contradiction here.

Trade

Jerzewska said the green lane offers solutions to problems raised by stakeholders: it simplifies procedures for a subset of goods, and she didn’t think there was ever an expectation that there would be no formalities.

Potential trade diversion from the Republic of Ireland to routes to GB through NI ports was discussed. Jerzewska noted that the Government had promised a system for ‘qualifying goods’ but she said this would be “incredibly technically difficult”, aside from the political aspect. She said there is anecdotal evidence of EU companies registering in NI for the purpose of moving goods and avoiding tariffs, especially for smaller volumes.

Howe highlighted the impact of labelling requirements (which are to be introduced gradually by 1 July 2025: all retail goods - with some exceptions - will be individually labelled ‘not for EU’). He said businesses would have to keep separate stock for NI, and some may say it’s uneconomic to do so and stop supplying the small NI market. The Belfast Telegraph reports on views of grocery retailers and suppliers on the Windsor Framework, particularly the impact of labelling requirements. The Telegraph reports that there is disquiet from some politicians about the labelling requirements, which the Government plans to apply across the whole of the UK. A Defra spokesperson said, “This is a proportionate and necessary means of ensuring goods moving in the green lane will only be sold to consumers in Northern Ireland.”

Whitten said the new arrangements could mean NI producers are undercut, as they may have more regulations to comply with than their counterparts in GB. She welcomed the new Special Body on Goods for assessing potential divergence of EU and UK rules, and that there is some acknowledgement in the architecture of the Framework of the need to discuss the implications of divergence. She also highlighted the possibility – through the use of the Stormont Brake – of NI being in a state of ‘dual divergence’: if NI has the older non-updated version of an EU law, which is not in place in the same form in either GB or Ireland. This issue is discussed in a paper for Brexit and Environment.

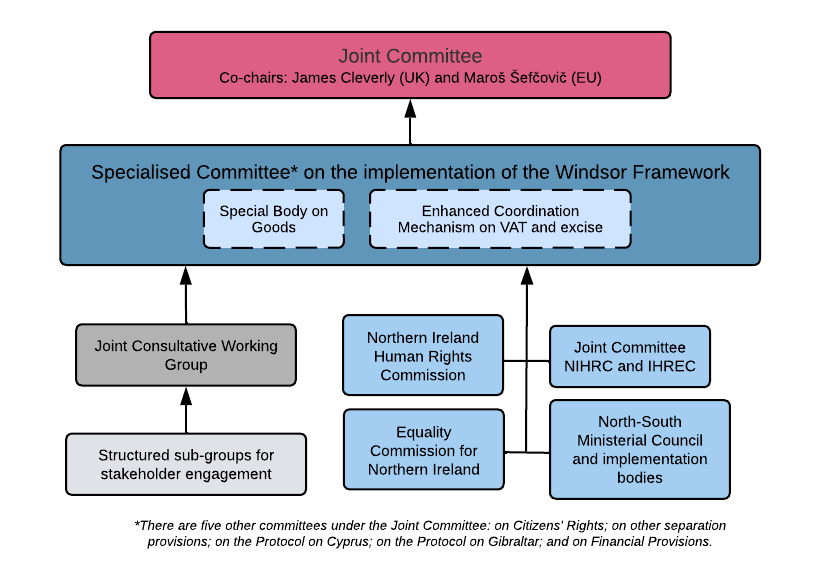

Governance structure of the Withdrawal Agreement and Windsor Framework

Jerzewska said on regulatory divergence, businesses are very clear what they want: from a practical perspective, divergence is not helpful if they are serving more than one market. Regarding parcels Jerzewska questioned whether carriers will take legal liability for the data submitted (as part of the authorised carrier scheme), which usually lies with the trader. She said there is much to be worked out on this, as well as on VAT.

Asked about the Government’s claim that the Framework removes 1,700 pages of EU law, Howe said there is some disapplication of some EU measures from certain activities in NI, but no general disapplication except for two articles on VAT and indirect taxes. He argued that the statement that there is a complete disapplication of these laws from NI is misleading. The Government has also stated that less than 3% of EU laws still apply to NI: Howe said he can’t even begin to understand what that claim could possibly be based on.

Regulatory divergence

A theme which has been raised repeatedly at the Lords Sub-Committee is EU-UK regulatory divergence: the committee has asked the Government what it is doing to monitor and address the “growing complexity and practical consequences of regulatory divergence for Northern Ireland.”

The UK in a Changing Europe think tank has published the seventh edition of its EU-UK divergence tracker for the period January to April 2023, authored by Joël Reland. The report refers to the Windsor Framework as ‘managed divergence’, noting it should reduce the extent of GB-EU divergence, and that the Framework addresses the significant ‘trade diversion’ of certain goods, which would have been planned under full implementation of the Protocol, e.g. sausages, and cakes with E171 food colouring. It notes the reductions in UK alcohol duty on draught alcohol at venues such as pubs – a reform which can now also apply in NI through the Windsor Framework.

The regulatory tracker finds 28 cases of divergence: 7 cases of active divergence (the UK changes its rules), 2 cases of active convergence (the UK aligns to EU rules), 17 cases of passive divergence (the EU changes its rules and the UK does not) and 1 case of internal divergence (in this case, Scotland plans to change its rules and the rest of the UK has not yet).

The UK has launched a consultation on a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM); its proposals are similar to EU plans for its own CBAM. Reland notes, “there is an additional, potentially highly-vexed question, over whether the EU CBAM applies in Northern Ireland.” The UK and EU could link their Emissions Trading Scheme, which would probably exempt UK exports from EU CBAM requirements. However, Reland also points out that the UK and EU ETS regimes “are at risk of diverging somewhat in scope, which could make them harder to link in future.”

The EU’s General Product Safety Regulation, formally adopted in April, will apply to NI manufactured goods under the Windsor Framework, but the report states a “heightened risk” that GB-based suppliers do not comply with the new rule, “because NI is a relatively small market and some may deem that compliance with the GPSR incurs higher costs than the amount of trade that would be lost from ending exports to NI”. It suggests the GPSR “could thus be an important test case for the Stormont Brake.”

The Scottish Government’s deposit return scheme is covered as an example of internal UK divergence. If no exclusion is granted for the regulation (which will require retailers in Scotland to add 20p to the price of single-use drinks cans and bottles, which can be reclaimed by customers when they recycle them) under the UK Internal Market Act, Scottish businesses will be at a competitive disadvantage in light of the greater regulatory requirements.

In his analysis of recent developments, Joël Reland remarks, “There are signs that companies across the UK may continue adhering to EU rules, even where they don’t have to under the [Windsor] Framework.” He cites the example of arsenic in baby foods, adding, ”the freedom offered by the Windsor Framework to minimise the application of EU regulation could prove rather immaterial.” Reland also highlights the Retained EU Law (REUL) Bill, arguing, “If the Prime Minister is serious about limiting regulatory divergence with Northern Ireland, it is vital that he ensures officials focused on the REUL Bill speak to those working on the Windsor Framework, to understand the interlinkages and impacts on the ground in Northern Ireland.”

Horizon Europe

Leo Docherty, UK Minister for Europe, was asked about negotiations on the UK’s association to the Horizon Europe programme, the EU’s €95.5 billion research and innovation funding programme. He said, “We are doing this [negotiation] in good faith, and we hope that the discussions will be successful. We are determined to secure a fair deal for researchers, businesses and taxpayers.” He said he would not give a running commentary on the talks. SNP MP Martyn Day noted comments from Owen Jackson, director of policy at Cancer Research UK, who says Pioneer, the Government’s proposed replacement for Horizon, does not “match up” to association to Horizon Europe.

In April, Sir Paul Nurse, Director of the Francis Crick Institute, told the Commons Science and Technology Committee that his understanding is that the EU’s financial deal is “generous and recognises the two-year hiatus, which was a possible sticking point”. He added, “I see no excuse whatsoever not to associate. If we do not associate, I see us drifting off into the cold north-east Atlantic rather by ourselves”. He said the UK “will get very lonely and we will not have the influence on the world that is appropriate for a science superpower, which I think all political parties and scientists absolutely want.”

The Lords European Affairs Committee published its report on the future UK-EU relationship on 29 April. It states that UK association to Horizon Europe and other EU research programmes “would be a win-win for the UK and the EU”, describing this as “collateral damage” in the impasse over the Protocol.

Other news

- The European Parliament is to vote today on legislation relating to Northern Ireland and the Windsor Framework. The three proposals cover tariff rate quotas, human medicines and SPS measures.

- The European Parliament Delegation to the EU-UK Parliamentary Partnership Assembly (PPA) met on 4 May to discuss support for Ukraine, mobility, and the EU’s new entry and exit system. The next PPA meeting will take place on 4-5 July 2023.

- On 3 May, the Commons European Scrutiny Committee held a session on post-Brexit financial services regulation.

- The Centre for Cross Border Studies has published the results of its 9th quarterly survey on North-South and East-West cooperation.

Sign up to Brexit and Beyond

Sign up for our regular Brexit and Beyond newsletter and get all the latest developments and news delivered straight to your inbox.