Report on the Employment (Zero Hours Workers and Banded Weekly Working Hours) Bill

Session: Session currently unavailable

Date: 04 February 2022

Reference: NIA 192/17-22

Report on the Employment (Zero Hours Workers and Banded Weekly Working Hours) Bill.pdf (387.4 kb)

Ordered by the Committee for the Economy to be published on 4th February 2022

Report: NIA 192/17-22 Committee for the Economy

Contents

- Powers and Membership

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms used in this Report

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Consideration of the Bill

- Clause by Clause Scrutiny of the Bill

- Links to Appendices

Powers and Membership

Powers

The Committee for the Economy is a Statutory Departmental Committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of Strand One, of the Belfast Agreement, and under Assembly Standing Order No 48. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Department for the Economy, and has a role in the initiation of legislation. The Committee has nine members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, and a quorum of five.

The Committee has power to:

- consider and advise on Departmental budgets and Annual Plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- approve relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee Stage of relevant primary legislation;

- call for persons and papers;

- initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister for the Economy.

Membership

The Committee has 9 members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, and a quorum of five members. The membership of the Committee is as follows

- Dr Caoímhe Archibald MLA (Chairperson)

- Mr Matthew O’Toole (Deputy Chairperson)

- Mr Keith Buchanan MLA

- Mr Stewart Dickson MLA

- Mr Stephen Dunne MLA

- Mr Michael Nesbitt MLA

- Mr John O’Dowd MLA

- Ms Claire Sugden MLA

- Mr Peter Weir MLA

1With effect from 10 February 2020 Mr John Stewart replaced Mr Alan Chambers

2 With effect from 8 February 2021 Mr Paul Givan replaced Mr Gary Middleton

3 With effect from 19 March 2021 Mr Gary Middleton replaced Mr Paul Givan

4 With effect from 12 April 2021 Mr Mervyn Storey replaced Mr Gordon Dunne

5 With effect from 1 June 2021 Mr Mike Nesbitt replaced Mr John Stewart

6With effect from 21 June 2021 Mr Peter Weir replaced Mr Christopher Stalford

7With effect from 21 June 2021 Mr Keith Buchanan replaced Mr Mervyn Storey

8 With effect from 5th July 2021 Mr Stephen Dunne replaced Mr Gary Middleton

9 With effect from 18th October 2021 Mr Matthew O'Toole replaced Ms Sinead McLaughlin

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms used in this Report

| Abbreviation/Acronym | Full explanation of Abbreviation/Acronym |

|---|---|

|

CIPD |

Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development |

|

DfE |

Department for the Economy |

|

LRA |

Labour Relations Agency |

|

NIC-ICTU |

Northern Ireland Committee – Irish Congress of Trade Unions |

|

NUS-USI |

National Union of Students – Union of Students in Ireland |

Executive Summary

1. This report sets out the Committee for the Economy’s consideration of the Employment (Zero Hours Workers and Banded Weekly Working Hours) Bill. The Bill consists of 19 clauses and no schedules. It has three main parts as outlined below:

- Part 1 (clauses 1- 7) contains provisions with regard to Zero Hours Contracts.

- Part 2 (clauses 8 -16) contains provisions with regard to introducing a system of banded hours.

- Part 3 (clauses 17-19) contains general provisions relating to interpretation and commencement.

2. The Bill is a Private Member’s Bill introduced by Jemma Dolan MLA and seeks to introduce a system of banded hours contracts for workers in Northern Ireland, whose employment is on the basis of a zero hours contract. The Bill also aims to impose a minimum payment where an employee is called out to work but is subsequently not given work and to make exclusivity terms unenforceable.

3. The Bill does not provide for an outright ban on zero hours contracts but offers a right to request banded hours. The Bill therefore maintains some flexibility but aims to ensure a more equal balance between employer and employee.

4. The Committee had a significantly reduced timeframe for scrutiny of the Bill given that it was introduced and referred to the Committee at a late point in the mandate. The Committee was also aware that advice from the Assembly Speaker had indicated that the Bill was one of a number of Private Members’ Bills which were unlikely to complete their passage through the Assembly before the end of the mandate.

5. The Committee agreed to carry out a preparative, high level consideration of the Bill as a starting point for more detailed scrutiny should the Bill proceed through the Assembly at a future date.

6. The Committee published a short survey and public consultation and sought views from a limited number of key stakeholders on the high-level principles of the Bill. The Committee received 6 responses to its survey and 6 written submissions from stakeholders.

7. The Committee sought advice from the Examiner of Statutory Rules in relation to the range of powers within the Bill to make subordinate legislation. The Examiner considered the Bill and Explanatory and Financial Memorandum and was satisfied with the rule making powers provided for in the Bill.

8. The Committee heard oral evidence from the Bill Sponsor Jemma Dolan MLA and sought the views of the Department in writing on the Bill, to which it received a detailed response.

9. The Committee considered and discussed the Bill at 9 meetings and held oral evidence sessions involving 6 stakeholders. The Committee agreed to reserve its position on the Bill, and did not undertake a clause by clause scrutiny.

10. There was general support for the general principles of the Bill from the oral and written evidence received, but also an acknowledgement of the need to maintain some flexibility. There is a general recognition that the use of zero-hour contracts can be motivated by a desire by some employers to avoid contractual and pay obligations and can leave employees without any security or predictable income.

11. Some are of the view that there is a place for flexible working arrangements and that zero hours contracts can, in certain circumstances, offer some benefit provided these are two-sided. This applies, for example, to students who may require different working patterns at different times of the year.

12. Many stakeholders also refer to the human rights and equality impact of zero hours contracts on employees and workers and the disproportionate impact on women, younger workers, part-time workers and ethnic minorities.

13. Some concerns have been highlighted that there may be a risk that employers could resort to more casual work arrangements to circumvent the Bill which could lead to even fewer employment rights. There are also concerns that bad employers could penalise workers who seek to access the protections of the Bill.

14. Some are of the view that the issue of zero-hour contracts should not be considered in isolation but should be part of a consideration of the wider employment law framework. A number of stakeholders have also highlighted the changes in the employment and working environment as a result of the pandemic.

15. The Committee is aware that the issue has been considered by the Assembly previously and that the Employment Act (Northern Ireland) 2016 provides for a wide enabling power to make regulations, none of which have been taken forward to date.

16. The Committee recognises the commitment within the New Decade New Approach’ agreement, which states in relation to Employment Rights that “the Executive should move to ban zero-hour contracts and that there is general support for the provisions within this Bill. However, it also acknowledges that this limited consultation has raised a number of complex issues which require significantly more detailed scrutiny and further discussion with the Department and stakeholders.

Introduction

Background to the Bill

17. The Employment (Zero Hours Workers and Banded Weekly Working Hours) Bill was introduced to the NI Assembly by Jemma Dolan MLA on 15th November 2021 and was referred to the Committee for the Economy for consideration in accordance with Standing Order 33(1) on completion of the Second Stage of the Bill on 31st January 2022.

18. At introduction, Jemma Dolan MLA made the following statement under Section 9 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998: 'In my view the Employment (Zero Hours Workers and Banded Weekly Working Hours) Bill would be within the legislative competence of the NI Assembly'.

19. The Bill as introduced provides for Banded Hours Contracts for workers whose employment is on the basis of short-hours. The Bill aims to provide certainty regarding the number of hours that a worker may typically expect to receive and the associated income and therefore provide more financial security. The Bill does not ban zero hours contracts.

20. The Bill also aims to impose a duty on an employer to pay a worker a sum equivalent to three hours work at their hourly rate on each occasion where an employee is called out to work but is subsequently not given work. In addition, the Bill places an obligation on the employer to keep work patterns under review every three months and to notify a worker in writing of their entitlement to banded weekly working hours where appropriate.

21. The Bill also makes exclusivity terms unenforceable thus making a term in a zero hours contract which seeks to prevent the zero hours worker from taking on other work unenforceable against that worker. The employer cannot demand that the worker does not do any work outside the zero hours contract.

22. The Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015, which amended the Employment Rights Act 1996 in GB makes exclusivity clauses in zero hours contracts unenforceable and grants powers to the Secretary of State to make provisions in such regulations to penalise employers who use such clauses.

23. Later, the Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices recognised the flexibility that zero hours contracts can bring to business in supporting changing market conditions and employment rates but highlighted that the flexibility required by business is not being reciprocated to the worker. The Review acknowledged that this “makes it very difficult for a person to manage their financial obligations, or for example secure a mortgage.

24. In the Republic of Ireland, Section 16 of The Employment (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2018 (“the 2018 Act”) amended the Organisation of Working Time Act 1997 by introducing a system of banded hours for workers. This allows a worker who consistently works more hours each week than their contract provides for, to request a change to the contract terms to be placed in a band of hours that better reflects the number of hours they have worked over a 12-month period.

25. It is estimated that the prevalence of ZHCs in Northern Ireland is approximately 11,000 workers representing approximately 1.3% of the workforce. Some stakeholders have suggested that this figure may be higher given that many workers employment status may not be recognised as ZHC.

26. The Nevin Economic Research Institute indicates that over one in three workers in Northern Ireland are employed in a more insecure form of employment, than that offered by the traditional standard. 20% of workers earn below the real living wage. The accommodation and food sector is particularly at risk of low pay, with 75% of workers earning below the real living wage.

27. In 2014, the Department for Employment and Learning consulted on the issue of zero hours contracts but no policy proposals were taken forward. The Employment Act (Northern Ireland) 2016 provides for a wide enabling power to make regulations. It inserted a new Article 59A into the Employment Rights (Northern Ireland) Order 1996. This permits the Department to develop further policy proposals and bring forward regulations for the purposes of preventing abuses in respect of ZHC by means of the affirmative procedure at a future point. No regulations have been made to date.

28. There is a commitment within the New Decade New Approach’ agreement, which states in relation to Employment Rights that “the Executive should move to ban zero hours contracts”.

Committee approach

29. The Committee had a significantly reduced timeframe for scrutiny of the Bill given that it was introduced and referred to the Committee at a late point in the mandate. The Committee was also aware that advice from the Assembly Speaker had indicated that the Bill was one of a number of Private Members’ Bills which were unlikely to complete their passage through the Assembly before the end of the mandate.

30. The Committee therefore proceeded to carry out a limited public consultation and to seek views from key stakeholders on the high-level principles of the Bill in order to present a report which provide a useful starting point for Committee deliberations on any future Bill.

31. The Committee wrote to the Department to seek its views on the Bill and received a detailed response which is included at Appendix 4.

32. The Committee carried out a three-week consultation on the Employment (Zero Hours Workers and Banded Weekly Working Hours) Bill from 7th February to 4th March 2022. The Committee published a media sign posting notice in the Belfast Telegraph, Irish News and Newsletter seeking responses to its Bill survey. The Committee received 6 responses to its survey along with 6 separate written submissions. The Committee would like to place on record its thanks to all who responded. Copies of the written submissions are included at Appendix 5. A copy of the survey summary report is provided at Annex 7.

33. The Committee also agreed a social media strategy to raise awareness of and engage with the public via social media to encourage participation in the Committee Stage of the Bill. Four social media platforms (NI Assembly Blog, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram) were used to disseminate information on the Bill.

34. During the period covered by this report the Committee considered the Bill and related issues at 9 meetings. The Minutes of Proceedings are included at Appendix 3.

35. The Committee had before it the Employment (Zero Hours Workers and Banded Weekly Working Hours) Bill (NIA 46/17-22) and the Explanatory and Financial Memorandum that accompanied the Bill.

36. At its meeting on 2nd February 2022, the Committee agreed a motion to extend the Committee Stage of the Bill to 25th March 2022. The extension requested by the Committee reflected the need to progress the legislation in a timely manner but also to ensure robust and detailed scrutiny by the Committee. The motion to extend was supported by the Assembly.

37. The Committee received an introductory briefing on the principles of the Bill from the Bill Sponsor Jemma Dolan MLA on 8th December 2021. The Committee also wrote to the Department seeking its views. The Committee heard oral evidence from the Women’s Policy Group; the Nevin Economic Research Institute; Northern Ireland Committee, Irish Congress of Trade Unions; UNISON; Retail NI; and Hospitality Ulster. The Minutes of Evidence are included at Appendix 4.

38. To assist consideration of specific issues highlighted in the evidence, the Committee commissioned a research paper from the NI Assembly Research and Information Service on the provisions of the Bill.

39. The Committee carried out its final deliberations on the Clauses of the Bill at its meeting on 16th March 2022 and decided not to carry out a formal clause by clause scrutiny of the Bill.

40. At its meeting on 16th March 2022 the Committee agreed its report on the Employment (Zero Hours Workers and Banded Weekly Working Hours) Bill and ordered that it should be published.

Consideration of the Bill

41. The Employment (Zero Hours Workers and Banded Weekly Working Hours) Bill introduces Banded Hours Contracts for workers whose employment is on the basis of short-hours. The Bill aims to provide certainty regarding the number of hours that a worker may typically expect to receive and the associated income and therefore provide more certainty and financial security.

42. The Bill also aims to impose a duty on an employer to pay a worker a sum equivalent to three hours work at their hourly rate on each occasion where an employee is called out to work but is subsequently not given work. The Bill also places an obligation on the employer to keep work patterns under review every three months and to notify a worker in writing of their entitlement to banded weekly working hours where appropriate.

43. The Bill makes exclusivity terms unenforceable meaning that a term in a zero hours contract which seeks to prevent the zero hours worker from taking on other work cannot be enforced against that worker.

44. As outlined above, the Committee had a relatively brief timeframe in which to consult and consider the clauses of the Bill. The Committee carried out a brief public consultation on the high-level principles of the Bill and sought written and oral evidence from a limited number of stakeholders.

45. Much of the commentary on the Bill is general and not specific to the clauses of the Bill given that stakeholders did not have adequate time to analyse or provide a view on each individual clause.

46. Below is a summary of the evidence in relation to this Bill. Whilst the Committee had some discussion around the issues raised in written and oral evidence, there was not adequate time for any detailed scrutiny or agreed recommendations.

47. Recognising that this Bill would not complete its passage through the Assembly in the current mandate, the Committee wished to present this report as a starting point for deliberations on any future Bill.

Clauses of the Bill

Clause 1: Zero Hours Workers

48. Clause 1 defines a zero hours worker as someone on a zero hours contract. A zero hours contract is defined as a contract where there is no guarantee that the worker will be given any work. Clause 1 covers employees and workers, but not a person on a non-contractual arrangement. In practice, this means that these provisions apply to workers, but not to someone classified as self-employed, or an independent contractor.

Clause 2: Zero hours worker called in but not given work:

49. Clause 2 provides for the situation where a zero hours worker is called in to work, but when they get there, they are not actually given any work (or given less than 1 hour’s work). Every time this happens, the worker is entitled to be paid as if they had worked for 3 hours. There is an exception. There is no entitlement to payment if there are exceptional circumstances (for example an emergency or accident, or the worker is ill) meaning that the worker wouldn’t be expected to do the work.

Clause 3: Exclusivity terms unenforceable

50. Clause 3 makes exclusivity terms unenforceable. This means that a term in a zero hours contract which seeks to prevent the zero hours worker from taking on other work is not enforceable against that worker.

Clause 4: Power to make further provision in respect of zero hours workers

51. Clause 4 replicates the existing power to make regulations setting out more laws for zero hours contracts. This clause retains the power to make regulations, not just in relation to workers and persons who are employees, but to persons in a non-contractual relationship with an employer, for example for independent contractors.

Clause 5 – Right not to be subjected to detriment:

52. Part 6 of the 1996 Order gives protection for workers and employees if they exercise particular rights, or in connection with particular things. Clause 5 adds to that list by stating that workers cannot be penalised (i.e. cannot be subjected to detriment) if they breach an unenforceable exclusivity clause of the sort referred to in clause 3. Clause 5(2) gives the worker a right to bring a claim to an industrial tribunal if this right is breached.

Clause 6 – Unfair dismissal

53. All employees have the right not to be unfairly dismissed, as set out in Part 11 of the 1996 Order. That Order goes on to state that if the dismissal is for certain reasons, it will be automatically unfair. Clause 6 adds to this list and states that if an employee is dismissed because they breached an unenforceable exclusivity term that will automatically constitute an unfair dismissal.

Clause 7 – Role of Labour Relations Agency in relation to conciliation

54. The Labour Relations Agency already has a role in promoting conciliation in a list of employment disputes. This clause adds complaints about zero hours contracts to that list.

Clause 8 – Entitlement to banded weekly working hours:

55. Clause 8 sets out the right of a worker to be placed in a band of weekly working hours. If the worker’s hours, as set out in their contract, do not reflect the actual hours they are working every week, the worker can request to be placed in a band of weekly working hours which accurately reflects the hours they are doing. Once placed in that band, the worker must then be given working hours, each week, which fall within that band.

Clause 9 – Employer’s obligation to inform worker of entitlement to banded weekly working hours

56. Clause 9 places an obligation on the employer to keep under review whether a worker is entitled to be placed in a band of weekly working hours.

Clause 10 – Procedure for placement in banded weekly working hours

57. Clause 10 sets out the procedure for a worker to be placed in a band of weekly working hours. After the worker makes the request, the employer has 4 weeks to comply. The band is calculated by reference to the average weekly working hours over the previous 3 months. The worker can make the request at any time, and may make requests even after a previous request has been refused if the circumstances have changed.

Clause 11 – Exceptions

58. Clause 11 sets out the exceptions where a worker isn’t entitled to be placed in a band. This includes where there is insufficient evidence to justify being placed in a band, or because the weekly hours have been in flux for some reason.

Clause 12 – Complaints to industrial tribunals

59. Clause 12 gives workers the right to bring a claim in the industrial tribunals around the failure of an employer to place them in a band of weekly working hours. The standard 3-month time limit to bring a claim in the industrial tribunals applies.

Clause 13 – Remedies

60. Clause 13 grants the industrial tribunals the power to require an employer to place a worker in a band of weekly working hours where it finds that the employer has broken the banded hours obligation.

Clause 14 – Application to zero hours workers:

61. Clause 14 provides that if a zero hours worker is placed in a band of weekly working hours, they cannot then be construed as being on a zero hours contract. This clause confirms that.

Clause 15 – Power to require records to be kept:

62. Clause 15 gives the Department the power to make regulations concerning the paperwork that employers must keep on the subject of banded weekly working hours.

Clause 16 - Role of Labour Relations Agency in relation to conciliation:

63. The Labour Relations Agency already has a role in promoting conciliation in a list of employment disputes. This clause adds complaints about banded weekly working hours to that list.

Response to the Call for Evidence

64. In response to the call for evidence, the Committee received 6 responses to its online survey which ran for a much shorter period than is usual from 7th February to 4th March 2022. The Committee received a further 6 written submissions from representative groups and stakeholders. The Committee appreciates the time and effort taken by individuals and representatives who provided evidence. The written submissions can be found at Appendix 3.

Committee Survey

65. The Committee highlights that the results of this survey must be viewed in the context of the limited number of only 6 responses received due to the short timeframe for consultation.

66. Of those who responded, the survey results indicate that all respondents agree that zero hours contracts should be replaced with ‘banded hour contracts’. Similarly, there was consensus that if a worker’s hours, as set out in their contract, do not reflect the actual hours they are working every week, the worker can request to be placed in a band of weekly working hours which accurately reflects the hours they are doing.

67. Survey responses indicate 100% support for the band structure as set out in the Bill. There was a 50/50 split in views in relation to whether the band should be calculated by reference to the average weekly working hours over the previous 3 months.

68. One respondent stated that while the banding approach is appropriate in principle, it is important to note that hours available for work in many sectors vary seasonally, with tourism, hospitality and retail key examples of this. Therefore, it is important to ensure clear rules that do not inadvertently penalise workers by encouraging use of a reference period with unusually limited hours.

69. There was also a 50/50 split in opinion in relation to the list of exceptions where a worker isn’t entitled to be placed in a band.

70. The survey asked about the list of exceptions where a worker isn’t entitled to be placed in a band. In relation to the exceptional circumstance of ‘significant adverse changes’, one respondent states that if adverse changes are expected to be long term, the employer should be required to make clear provisions for staff, rather than prolonging use of zero hours contracts. This provision would increase and deepen uncertainty for workers in an already uncertain situation, and would disproportionately disadvantage those in the most precarious positions.

General Comments

71. The Committee heard from a number of stakeholders that whilst they welcomed the opportunity to put forward their views on the Bill, they were of the view that the timeframe was too tight to allow for adequate consultation, particularly amongst membership organisations.

72. Women’s representatives and trade unions in particular highlighted that there was not time for any meaningful consultation amongst their membership, particularly given that such legislation may have particular implications on women, people in part-time and migrant and lower paid workers.

73. Retail NI and Hospitality Ulster highlighted offered general views in their oral evidence but also highlighted that there is a need for more detailed consultation with their members on the Bill.

74. All stakeholders were generally supportive of the aims of the Bill with some specific issues raised as outlined in more detail below. Many also highlighted the need to ensure that there is a built-in flexibility for circumstances where zero hours contracts might be desirable to both employers and workers.

75. Many stakeholders have outlined the negative impact of zero hours contracts on workers and the need for issues around lack of financial security and exploitation of workers to be addressed. Therefore, stakeholders have stated that whilst the Bill is not perfect, it represents a step forward.

76. NIC-ICTU outlines that predictable income is probably the most important aspect of work, as it is the basis for planning life. It states that not knowing what you will be earning from day to day can be a life lived in fear and anxiety, particularly if you have a family depending on your wage. In such a precarious lifestyle, you are unable to budget, get a mortgage or a bank loan, you struggle to pay bills and rent, you are unable to plan for life outside of work if you have childcare responsibilities or other caring responsibilities. It also highlights that fluctuating hours mean that it is difficult to claim in-work benefits, and for many people, when they do get benefits, they are delayed thus intensifying the hardship.

77. NIC-ICTU states that the Bill is a move in the direction of creating a more balanced, modern and flexible employment model, where workers and employers can agree the type of flexibility that suits both parties.

78. The Women’s Regional Consortium highlights the links between precarity of employment, particularly zero hours contracts, and in-work poverty. It also states that, while it is important to ban these types of contracts, it does not deal with other issues in the labour market such as low pay, precarious and involuntary part-time work which give rise to many of the same impacts for employees particularly women.

79. The Labour Relations Agency (LRA) highlight that employment policy such as this prompts a range of responses from different stakeholders depending on the prism through which they are being viewed. The LRA also points to polarised opinions associated with their use and existence.

80. The Equality Commission, whilst it has not formed a view on the Bill, refers to its ‘Statement on Key Inequalities in Employment’ and highlights the particular issues relating to the link between part-time working and low pay and precarious employment, such as zero hours contracts, in the context of the employment of women, lone parents with dependents, and carers. It also highlights issues relating to migrant workers and agency workers.

81. The CIPD supports the aims of the Bill but not an outright ban, and states that although it does not delve into the detail of various clauses, there is much in the Bill that it would support. It states that there are some areas where more work is required and requires further consultation with members to provide more specific feedback. It highlights research outlined in more detail below which points to some benefits of zero hours contracts which is why it does not support an outright ban.

82. The CIPD states that the key issue is whether the Bill is the most appropriate vehicle for change in this area, especially given likely developments in GB law as well as ongoing work by the Department for the Economy. As Covid restrictions ease, it hopes to see legislative proposals in relation to variable hour contracts from the UK Government soon and these may need to be considered in a Northern Irish context.

83. The CIPD states that many of the issues that the Bill seeks to address are currently the subject of ongoing work across the rest of the UK. It highlights that its members working for UK-wide organisations are of the view that the complexity of navigating the growing differences between GB and NI employment legislation is becoming a significant burden. It adds that there may be good reasons for some tailored legislation, but the overall preference from its members is for broad consistency across the UK.

84. The CIPD’s view remains that there is demand for these types of arrangements from employees as well as employers and, if used well, they can be suitable to both.

85. In oral evidence, Hospitality Ulster stated that there is a place for flexible working in the hospitality industry as long as it is not abused and that the zero-hour rota model suits a section of the workforce at certain stages of their life.

86. Retail NI in oral evidence highlighted that banded-hours working is, more or less, normal practice for a lot of its members and that there is very little evidence of any use of zero hours contracts. Retail NI states that there is a need to ensure that the Bill locks in flexibility for employers and staff.

87. NIC ICTU fully supports the Bill, although makes the point that it is not the ban on zero-hours contracts agreed in the New Decade, New Approach agreement. It states that the Bill is a move in the direction of creating a more balanced, modern and flexible employment model, where workers and employers can agree the type of flexibility that suits both parties.

88. The Department’s view is that while there may be a need to regulate to prevent misuse of zero hours contracts, it is important to note that flexibility in the labour market can also be a positive feature for many businesses. It states that employment law is complex and no employment right can be considered in isolation from the rest of the employment law framework. Given the complexities of this issue, the Department wishes to highlight the necessity to scrutinise any new legislation fully to ensure it is operable.

89. Other more specific issues raised in the written submissions are summarised below.

Zero Hour Contracts Use and Definition

90. The CIPD states that the Bill seeks to introduce the right to request banded hours contracts to those who consistently work more hours than they are contracted to. It suggests that this would extend well beyond those on zero-hours contracts. It outlines that an analysis of the latest data suggests that over 7 million employees across the UK say their hours tend to vary, of which only a fraction (less than a tenth of these) do not have guaranteed minimum hours. The CIPD contends that the Bill would therefore apply to a significant proportion of the workforce and constitute a considerable change to employment law in Northern Ireland.

91. The LRA points to a lack of understanding regarding where zero hours contracts sit within the wider employment status policy debate (independent contractor, worker, or employee). And, from here, the need to examine policy direction through the employment status lens and wider future direction on legislating around ‘worker’ rights.

92. The LRA highlights the inability for some to conduct definitive workforce planning due to ongoing business uncertainties, thereby necessitating the use zero hours contracts as a business model requiring maximum flexibility at the lowest potential outcome cost.

93. The LRA highlights the lack of certainty regarding how zero hours contracts are defined per se by Government departments, employers, statisticians etc and how they pertain to the discussion around ‘atypical’ employment models, practices and rights.

94. The LRA states there are competing narratives around workers who want to be on zero hours contracts in terms of specialist freelancers versus precarious workers, who have no choice on the prevailing business model.

95. Retail NI suggested that, although specific data has not been gathered, they do not believe that zero-hour contracts are widely in use in this sector.

96. The Department outlines that the Bill would make amendments to commonly used definitions of worker and employee and would give workers who do not have employee status the same entitlements as employees in certain circumstances. The Department explains that the definition within the Bill are different to the existing definitions of “employee” and “worker” used throughout employment legislation. In particular, it is noted that there is no reference within this definition to performing “services”. This is a common element of other employment related definitions of “worker”.

97. The Department explains that it is not in a position to comment on the rationale for the exclusion of reference to “services” within the proposed definition. It suggests that should the Bill progress further, consideration would need to be given to the potential for any unintended consequences of amending this commonly used definition within employment law – including whether the lack of reference to performing “services” may impact upon the number of workers that could fall within the proposed definition of zero hours worker.

Disproportionate impact of zero hours contracts on certain groups e.g. women and part-time, lower paid and migrant workers

98. The Women’s Regional Consortium states that statistics show that people on zero hours contracts are more likely to be young, part-time, women or in full-time education when compared with other people in employment. Single parents (who are mostly women) are twice as likely to have a zero-hours contract as other family types. It suggests there are more women employed on zero hours contracts (3.6%) than men (2.8%) and that these statistics help to show the gendered nature of these contracts.

99. The Equality Commission, whilst not taking a position on the Bill, referred to its ‘Statement on Key Inequalities in Employment’ and highlighted the particular issues relating to the link between part-time working and low pay and precarious employment, such as zero hours contracts, in the context of the employment of women, lone parents with dependents, and carers. It also highlighted issues relating to migrant workers and agency workers.

100. The Equality Commission states that precarious employment, such as zero-hour contracts, tends to be found in the hospitality and health and social care sectors, where a high proportion of women work. It also indicated that it has been reported that zero hours contracts are associated with lower gross-weekly pay, fewer hours of work on average and may contribute to rates of under-employment.

101. NIC-ICTU states that the Bill could have a positive impact on the lives of many vulnerable workers, including women, young and migrant workers, who tend to be disproportionately affected by zero-hours contracts.

102. NIC-ICTU referred to a project run between 2017-2020, along with Ulster University, the Migrant Rights Centre Ireland and the Community Intercultural Programme to assist vulnerable migrant workers mainly in the agri-food sector here. The project gathered evidence of the mistreatment and exploitation of large numbers of vulnerable newcomer migrant workers. The project recorded widespread misuse of zero hours contracts in the agri-food sector in Northern Ireland.

103. NIC-ICTU states that some employers adopted the use of zero hours contracts as a normal business model in an effort to undercut competitors. The majority of their workforces were vulnerable migrant workers employed on zero hours contracts who did not know from day to day whether they would have work, and if they did get working hours, paid at national minimum wage rates, they were unsure how long they would be each day. The project also recorded the prevalence of discrimination against pregnant women whose working hours evaporated on telling the employer of their status.

104. NIC-ICTU also highlights the use of zero hours contracts in the health and social care sector. NIC-ICTU explains that currently, with the outsourcing of social care, ZHCs have become the predominant arrangement in social care provided by private contractors. It adds that ZHCs create major problems for retention of skilled workers, workforce planning, care standards and quality and quantum of care. It suggests that many care workers in this sector in particular have simply moved on to something with fewer risks and better pay, at a time when we know that the commitments of the social care sector mean that we have to expand.

Potential benefits of zero hours contracts

105. There was some reference amongst stakeholders to whether there may be a place for zero-hour contracts in some circumstances where more flexibility is required.

106. As outlined by the LRA, one group of stakeholders may view zero hours contracts as the last bastion of necessary employment flexibility and they remain an essential aspect of working life. Others view zero hours contracts as exploitative by their very nature and, as such, should be banned outright.

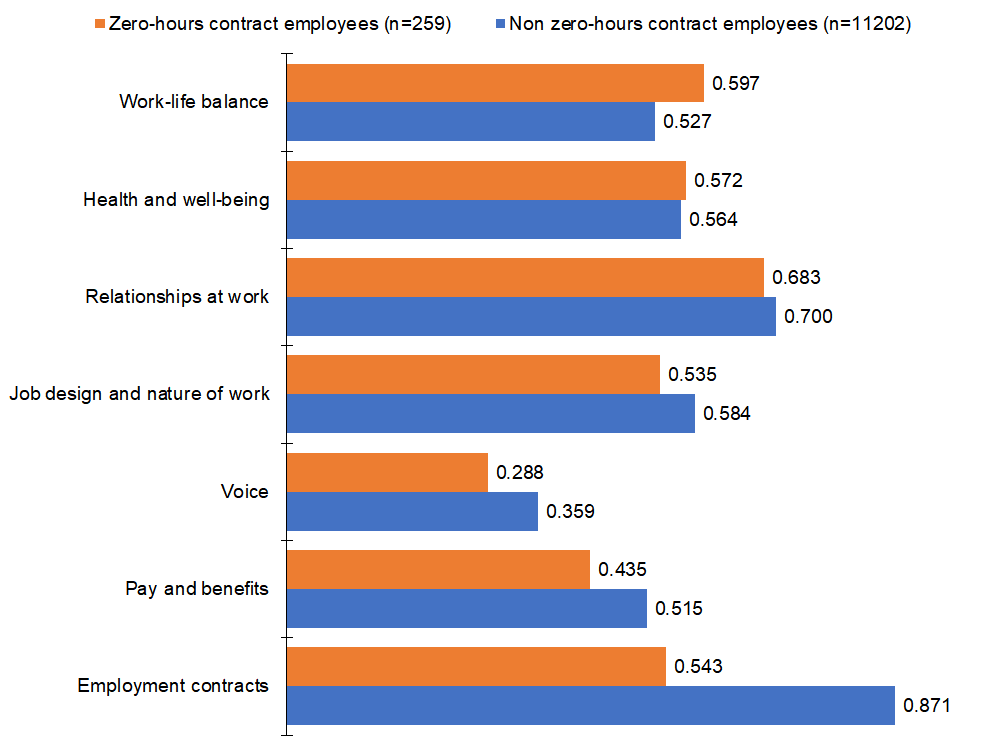

107. The CIPD provides evidence in relation to job quality and zero hours. The CIPD carries out and annual Good Work Index and provides the following UK-wide data for zero-hours contract workers:

Figure 2: Good Work Index for zero-hours contract workers 2019-2021

108. The CIPD highlights that the biggest differences are across the ‘employment contracts’ and ‘pay and benefits’ dimensions. However, it points to comparable scores across the other dimensions and, in fact, higher scores on work-life balance and marginally so on health and wellbeing. It suggests that this is because most zero-hours jobs tend to involve part-time hours and because zero-hours jobs “spill over” less into the rest of employees’ lives, the result being less workload pressure and less stress. It points to some of the trade-offs that it sees in research around job quality and highlights that for some, zero-hours contracts can work well. It also states that employer research suggests that three-quarters (76%) of employers who use zero-hour contracts say they treat those on them as employees. This is corroborated by official ONS data which show that almost two-thirds (64%) of people on zero-hours contracts have a permanent role and so are likely to have full employment rights, subject to length of service.

109. The CIPD’s view remains that there is demand for these types of arrangements from employees as well as employers and, if used well, they can be suitable to both.

110. The NUS-USI states that zero-hours contracts can be useful in some circumstances, particularly for students who require flexible working hours. However, the imbalance of power between an employer and employee means that very often it is only the employer who is able to enjoy the full benefits of flexibility, while employees are afraid of turning down shifts in case they lose hours.

111. The NUS-USI suggests that care should be taken to ensure that this measure does not disadvantage workers who require different working patterns throughout the year. NUS-USI previously recommended considering a minimum number of hours per year guaranteed to workers, which would allow for flexibility throughout a longer time period.

112. Both Retail NI and Hospitality Ulster point to the fact that there may be a place for more flexible working provided that there some built-in mechanisms to ensure it is not abused. They also point to the challenges faced by both sectors as a result of the pandemic and the resulting need to support flexible ways of working.

Introduction of Banded Hours

113. The CIPD states that it particularly welcomes the more nuanced approach the Bill is taking to the issue, seeking to introduce a right to request banded hours contracts as opposed to an outright ban on zero-hours contracts. As outlined above, the CIPD also highlighted that the right to request banded hours contracts could extend well beyond those on zero-hours contracts.

114. The NUS-USI welcomes the proposal to introduce minimum hours bands. It suggests that this provides some much-needed certainty for individuals allowing them to more effectively plan their schedules and finances. However, it highlights that student workers often require different hours at different times of the year. A student who is comfortable working 12 hours per week during term time may seek to work more in holiday periods, or less during exam periods. Therefore, care should be taken to ensure that this measure does not disadvantage workers who require different working patterns throughout the year. NUS-USI previously recommended considering a minimum number of hours per year guaranteed to workers, which would allow for flexibility throughout a longer time period.

115. NIC-ICTU is deeply concerned that, you could have a worker placed on a band, conceivably the lowest band, 3 to 6 hours, called into work on a particular day and then denied hours when they arrive. While those who chose to remain on zero-hours contracts are given work. This could be used by bad employers to penalise workers who seek to access the protections of the Bill.

116. NIC-ICTU calls on the Committee to look at amending the Bill to close that potential loophole. NIC ICTU recognises that even if this Bill, with our suggested amendment, becomes law some unscrupulous employers will still seek to find ways around its protections.

117. In terms of the qualifying period for banded hours, the Women’s Policy Group also highlights concerns that the period of three months could inadvertently advantage less responsible employers. It makes the point that if there is knowledge that somebody has to be in a job for a continuous period of three months to qualify for a banded contract, employers who are keen to avoid that and are happy not to give their workers rights may have a constant short-term churn of employees where they employ them for two or two and a half months before removing them in order that they do not qualify for a banded contract.

118. Retail NI stated that banded-hour working is already normal practice for many of its members.

119. The Department outlines that the Bill, as drafted, applies the entitlement to banded weekly working hours to all workers - not just “zero-hour workers”.

120. The Department explains that the proposed entitlement arises where the worker’s weekly hours, as set out in their contract, do not reflect the number of hours worked per week during the reference period (proposed Article 112J(2)). It states that it has not had time to determine what the potential repercussions of this might be (if any), given the significant variations that exist in different types of employment contracts.

121. The Department also refers to the proposed three-month reference period for determining a banded hours contract. It highlights that this is in contrast to the banded hours reference period that is applied in the Republic of Ireland, where a twelve-month reference period is in place. It states that should a proposed system of banded hours be implemented, it would be necessary to determine the appropriate reference period. Factors to be considered would include, but not be limited to, the impact of seasonal variations in working hours, and whether it might incentivise employers to offer a wider pool of short term or fixed term contracts.

122. The Department also refers to the provision in the Bill requiring that every three months, an employer must consider whether a worker may be entitled to banded weekly working hours. It states that, in practice, this has the potential to place a significant administrative burden on employers who will have to make an offer to each qualifying worker at repeated three-month intervals from the date they take up employment, unless the worker opts to accept the offer to move to a banded hours contract.

Minimum payment when called out to work but not given work

123. The CIPD states that it would welcome a day one right to a reasonable notice of shifts, a 24-hour cut off point for cancelling shifts and compensation for shifts cancelled at short notice. The CIPD states that it should be noted that short notice shift, or hours, cancellations happen to workers with variable hours more generally and not just those on zero-hours contracts. It states that in contrast with the banded hours proposals in the Bill, the compensation proposals are much narrower. They also do not include any provisions around the notification of shifts, which CIPD argue should be included.

124. The CIPD adds that many of the issues that the Bill seeks to address are currently the subject of ongoing work across the rest of the UK.

125. The NUS-USI welcomes the proposal to introduce a minimum payment for workers who are called in but then not given work. It states that this can cause a significant amount of uncertainty and result in additional costs to workers, such as transport and childcare costs. Zero hours contract workers are often ‘on call’ all the time, waiting for the opportunity to be given work. This can cause a lot of disruption to their lives and cause significant stress.

126. As well as protecting workers who are called in but not given work, the NUS-USI would also support government considering if there is anything else which can be done to ensure that employers give due notice of upcoming work shifts as far as possible.

Exclusivity Clauses

127. Stakeholders highlight that Northern Ireland is behind the rest of the UK having not yet banned exclusivity clauses and generally welcome a ban on exclusivity clauses.

128. Retail NI and Hospitality Ulster indicated in their oral evidence that, similar to zero hours contracts, they do not believe exclusivity clauses are widely used although highlighted that they had not had the opportunity to gather statistics.

129. The NUS-USI welcomes the introduction of an effective ban on exclusivity clauses which it called for in its response to the government consultation in 2014.

130. The CIPD states that it supports these measures, but that the aims of the relevant clauses have now been overtaken by events. It outlines that, at the time of drafting, similar provisions included in the 2016 Employment Act were not yet in force. Clause 4 in the proposed Bill replicates provisions in clause 18 of the 2016 Act. The power to tackle the abuse of zero hours contracts (which is also likely to include a ban on exclusivity clauses) has now been enacted by the Employment Act (Northern Ireland) 2016 (Commencement No.4) Order (Northern Ireland) 2021, with regulations to follow soon.

131. The Department outlines that is not aware of any evidence to suggest that the use of exclusivity clauses for those on a zero hours contract is a common practice in Northern Ireland but acknowledges that it is difficult to envisage a circumstance where it would be appropriate for an employer to not give any hours and at the same time prevent a worker from seeking work elsewhere.

Clause 14

132. A number of stakeholders have raised specific issues in relation to Clause 14 of the Bill which provides that if a zero hours worker is placed in a band of weekly working hours, they cannot then be construed as being on a zero hours contract.

133. NIC-ICTU states that, if that is the case, according to the Bill, they will no longer be protected from the ban on exclusivity clauses or compensated for being called into work and not being given any hours. This would clearly mean that the protections such as those for Zero hours worker called in but not given work, and the unenforceability of “Exclusivity terms”, no longer apply to a banded worker.

134. The Women’s Policy Group in oral evidence outlined that, while that is not problematic in itself, when combined with the loss of new rights being afforded to zero-hours workers through the Bill, it could place those on lower bands in a more disadvantaged position if they are unable to look for more work. It states that clause 3 makes exclusivity terms on zero-hours workers unenforceable. That is a move that will enable those on very low incomes or contracts to seek more work and improve their standard of living. It is a massive step forward for the rights of workers on zero-hours contracts. The concern comes in, however, where the protection from exclusivity clauses does not seem to transfer to workers on the new banded-hours contracts. That protection would be especially important in order to enable those on lower bands to seek more work.

135. The Women’s Policy Group is also concerned that zero-hours workers may be unaware of the new rights if and when the Bill comes into effect. It states that strategies should be developed to ensure that zero-hours workers are aware of the unenforceability of any exclusivity clauses under which they previously worked.

136. The Women’s Policy Group also calls for the consideration of further remedies for inclusion in Clause 13, possibly including powers similar to those upholding the national minimum wage, under which employers who do not comply with the legislation may be fined by HMRC. It states that many workers are scared to kick up a fuss or take their employer to a tribunal for fear of retaliation or declining standards of employment, so any provisions that could be included in the Bill to encourage employers to comply proactively with the new regulations and the obligations contained therein would be welcomed by the Women's Policy Group.

Role of the Labour Relations Agency

137. The LRA outlines the view that there is that there is a lack of understanding that the Agency cannot conciliate in a dispute regarding the dismissal of a ‘worker’ because only employees have the right to claim unfair dismissal and most zero hours workers are legally classified as ‘workers’.

138. The LRA also points to the potential for other non-legislative initiatives regarding zero hour contracts such as a semi statutory code of practice on the responsible use of zero hours contracts, zero hours covenants, and charters associated with certain industries such as hospitality and so on.

Clause by Clause Scrutiny of the Bill

139. As the Committee decided to reserve its position on the Bill it did not undertake a clause by clause scrutiny and agreed to present the evidence it received as part of this Committee Report for consideration by the Assembly should the Bill proceed at a future date.

Links to Appendices

Appendix 1 – Minutes of Proceedings

- Wednesday 16th March 2022

- Wednesday 9th March 2022

- Wednesday 2nd March 2022

- Wednesday 23rd February 2022

- Wednesday 16th February 2022

- Wednesday 9th February 2022

- Wednesday 2nd February 2022

- Wednesday 26th January 2022

- Wednesday 19th January 2022

- Wednesday 8th December 2021

Appendix 2 - Minutes of Evidence

- Wednesday 16th March 2022: Committee report

- Wednesday 9th March 2022 – RaISe briefing

- Wednesday 2nd March – Consideration of written submissions

- · Wednesday 23rd February 2022 - Women’s Policy Group

- Wednesday 16th February 2022 - Nevin Economic Research Institute; Northern Ireland Committee, Irish Congress of Trade Unions; UNISON

- Wednesday 9th February 2022 - Retail NI; Hospitality Ulster

- Wednesday 2nd February 2022

- Wednesday 26th January 2022

- Wednesday 19th January 2022

- Wednesday 8th December 2021 – Ms Jemma Dolan MLA

Appendix 3 - List of Written Submissions

- Women’s Regional Consortium

- Labour Relations Agency

- Equality Commission for Northern Ireland

- CIPD

- NIC-ICTU

- NUS-USI

Appendix 4 – Papers from the Department

Appendix 5 – Research Papers

Assembly Research and Information Service (RaISe) papers considered:

Appendix 6 – List of Witnesses

- Mr Joel Neill, Hospitality Ulster

- Mr Glyn Roberts, Retail NI

- Mr Paul Mac Flynn, Nevin Economic Research Institute

- Mr Kevin Doherty, Northern Ireland Committee, Irish Congress of Trade Unions

- Ms Patricia McKeown Northern Ireland Committee, Irish Congress of Trade Unions (UNISON)

- Ms Alex Brennan, Women's Policy Group

- Ms Caoímhe McNeill, Women's Policy Group

- Ms Clare Moore, Women's Policy Group

- Ms Alexa Moore, Women's Policy Group