Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland

Session: 2011/2012

Date: 26 April 2012

Reference: NIA 38/11-15

ISBN: 978-0-339-60423-0

Committee: Justice

review-judicial-appointments.pdf (5.34 mb)

Committee for Justice

Session 2011/15

First Report

Review of Judicial Appointments

in Northern Ireland

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the Committee relating to the Report,

Minutes of Evidence, Written Submissions, Northern Ireland Assembly Research

and Information Service Papers and Other Papers

Ordered by the Committee for Justice to be printed 26 April 2012

Report: NIA 38/11-15 (Committee for Justice)

Membership

The Committee has eleven members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of five members.

The membership of the Committee during the current mandate has been as follows:

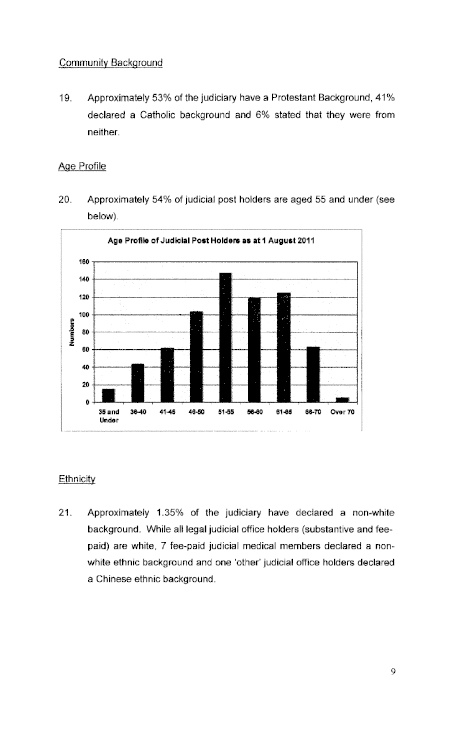

Mr Paul Givan (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Mr Stewart Dickson

Mr Tom Elliott[1]

Mr Séan Lynch

Mr Alban Maginness

Ms Jennifer McCann

Mr Patsy McGlone[2]

Mr Peter Weir

Mr Jim Wells

[1] With effect from 23 April 2012 Mr Tom Elliott replaced Mr Basil McCrea.

[2] With effect from 23 April 2012 Mr Patsy McGlone replaced Mr Colum Eastwood.

Table of Contents

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

NI Assembly Research and Information Service Papers

Appendix 5

Executive Summary

- The Northern Ireland Act 2009 made amendments to the process of judicial appointments and removals as set out in the Judicature (Northern Ireland) Act 1978 and the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002 (as amended by the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2004).

- Section 29C of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, as amended by Schedule 6 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009 (the 2009 Act), states that Standing Orders shall require one of the committees established by virtue of section 29 or the committee established by virtue of section 29A of the 1998 Act to review the operation of the amendments made by Schedules 2 – 5 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009.

- Initially the Assembly and Executive Review Committee was to undertake the review however following the devolution of policing and justice it was agreed that the responsibility for the review should pass to the Committee for Justice and Standing Orders were amended accordingly.

- The requirement to report on the review by 30 April 2012 provided restricted time to complete the review and the Committee therefore agreed to undertake a targeted consultation with key stakeholders and to place information on the review on the committee webpage.

- The Committee received eight written submissions and held three oral evidence sessions with the Attorney General for Northern Ireland, the Lord Chief Justice in his capacity as Chairman of the NI Judicial Appointments Commission (NIJAC) with other NIJAC representatives and a representative from the Office of the Lord Chief Justice, and the NI Judicial Appointments Ombudsman.

- Due to the limited time available the Committee's deliberations, which are set out in the section of the report covering consideration of the issues, were confined to a small number of issues including the appointment process for Appeal Judges, the composition of NIJAC, whether judicial appointments are reflective of the community in Northern Ireland and the role of elected representatives.

Committee Conclusion and Recommendation

- Having considered the evidence received and noting that the Department of Justice and NIJAC are of the view that the arrangements created by the 2009 Act, while only in place for a relatively short period of time, appear to be working satisfactorily, the Committee recommends that there should be no changes to the current process for judicial appointments and removals in Northern Ireland at this time.

- Given the statutory requirement to report to the Assembly by 30 April 2012, which restricted the time available to complete this review, and the fact that a number of issues may merit further consideration, the Committee intends to undertake a further review of the Judicial Appointments and Removals processes.

Introduction

Background

1. The Northern Ireland Act 2009 made amendments to the process of judicial appointments and removals as set out in the Judicature (Northern Ireland) Act 1978 and the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002 (as amended by the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2004).

2. Section 29C of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, as amended by Schedule 6 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009 (the 2009 Act), states that Standing Orders shall require one of the committees established by virtue of section 29 or the committee established by virtue of section 29A of the 1998 Act to review the operation of the amendments made by Schedules 2 – 5 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009.

3. Initially Standing Order 59 (4A) required that the Assembly and Executive Review Committee should undertake the review of the operation of the amendments made by Schedules 2 – 5 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009. Following the devolution of policing and justice and the establishment of the Committee for Justice discussion took place regarding which committee would be best placed to carry out the review. Agreement was reached that responsibility should pass to the Committee for Justice and the Chairman of the Assembly and Executive Review Committee subsequently wrote to the Committee on Procedures to request that Standing Orders be amended accordingly. A copy of the relevant correspondence is included at Appendix 5 in the report.

4. The Standing Orders of the Assembly were subsequently amended on 28 November 2011 and Standing Order 49 A states:

"(1) The statutory committee established to advise and assist the Minister of Justice (in this Standing Order referred to as 'the Committee for Justice') shall –

(a) review the operation of the amendments made by Schedules 2 to 5 to the Northern Ireland Act 2009;

(b) report on its review by 30 April 2012; and

(c) include in its report any recommendations it has for changes to the way in which judicial office holders are appointed and removed."

The Committee's Approach

5. At its meeting on 2 February 2012 the Committee agreed the following terms of reference for the Review of Judicial Appointments:

The Committee for Justice will:

(a) review the operation of the amendments made by Schedules 2 to 5 to the Northern Ireland Act 2009;

(b) identify any issues in the operation of these amendments;

(c) if applicable, make recommendations for changes to the way in which judicial office holders are appointed and removed; and

(d) report on the review by 30 April 2012.

6. Given the limited time available to complete the review the Committee agreed to undertake a targeted consultation with the following key stakeholders and to place information on the review on the committee webpage:

- The NI Judicial Appointments Commission

- The NI Judicial Appointments Ombudsman

- The Lord Chief Justice

- The Attorney General for Northern Ireland

- The Lord Chancellor

- The First Minister and deputy First Minister

- The Minister of Justice

- The Assembly and Executive Review Committee

- The Committee for the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister

- The Political Parties represented in the Assembly

- The two Independent Members in the Assembly

- The Law Society of Northern Ireland

- The Bar Council

7. The Committee received eight written submissions which are included at Appendix 3 in the report and held three oral evidence sessions with the Attorney General for Northern Ireland, the Lord Chief Justice in his capacity as Chairman of the NI Judicial Appointments Commission (NIJAC) with other NIJAC representatives and a representative from the Office of the Lord Chief Justice, and the NI Judicial Appointments Ombudsman. The Minutes of Evidence (Hansards) of the evidence sessions are included at Appendix 2 of this report. The Minutes of Proceedings relevant to this review are included at Appendix 1.

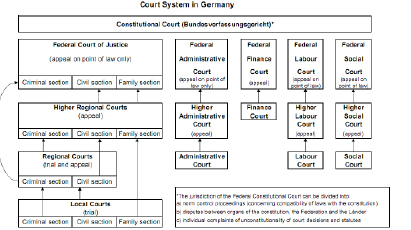

8. To assist the Committee's consideration of the process of judicial appointments and removals in Northern Ireland a background paper setting out the amendments made by Schedules 2 – 5 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009 was prepared and is included in the report at Appendix 5. The Committee also commissioned research papers on the process of judicial appointments in Northern Ireland, the models of judicial appointment in America and Germany and the process of appointments to the Court of Appeal in England and Wales and how it differs from the process in Northern Ireland. The research papers are included in the report at Appendix 4.

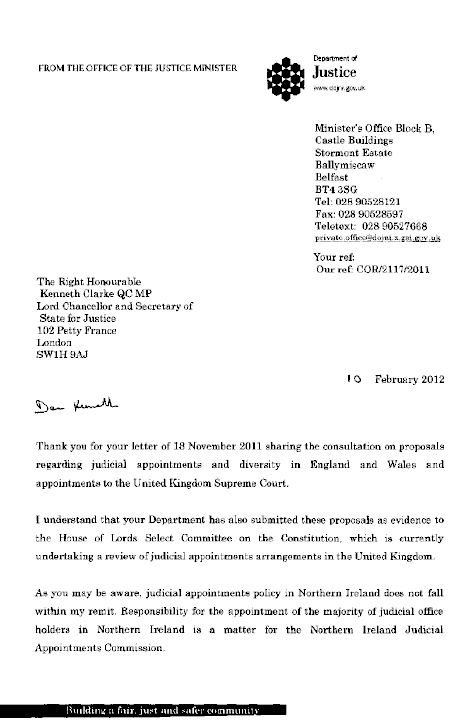

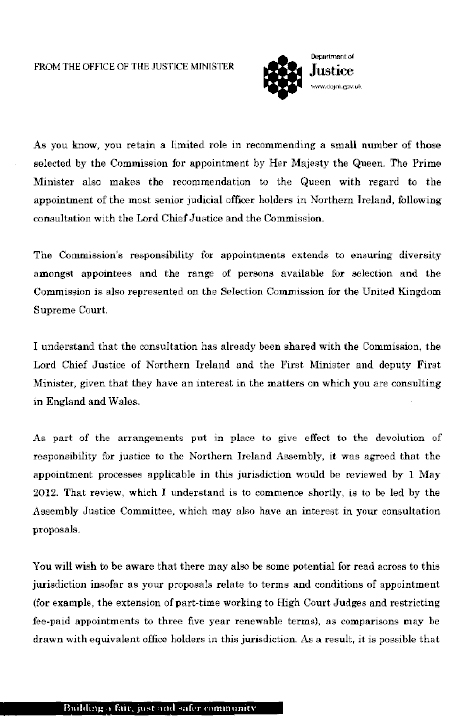

9. While undertaking the review the Committee was cognisant of the on-going House of Lords Constitution Committee Inquiry into the judicial appointments process for the courts and tribunals of England and Wales and Northern Ireland and for the UK Supreme Court and that the Ministry of Justice had just completed a consultation on appointments and diversity relating to the judiciary in England and Wales. The House of Lords Constitution Committee published its Inquiry report on 28 March 2012 and the formal response to the Ministry of Justice consultation should be available in April 2012.

10. Due to the limited time available the Committee's deliberations, which took place on 27 March 2012 and 19 April 2012, were confined to a small number of issues including the appointment process for Appeal Judges, the composition of NIJAC, whether judicial appointments are reflective of the community in Northern Ireland and the role of elected representatives.

11. At the meeting on 26 April 2012 the Committee agreed its report on the Review of Judicial Appointments and ordered that it should be printed.

Summary of Evidence

12. During its Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland the Committee received 8 written responses and heard oral evidence from the Attorney General for Northern Ireland, the Lord Chief Justice, Sir Declan Morgan, in his capacity as Chairman of the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Commission (NIJAC), together with representatives from NIJAC and the Office of the Lord Chief Justice, and the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Ombudsman, Mr Karamjit Singh. A copy of the written evidence received is at Appendix 3 and the Minutes of Evidence of the three oral evidence sessions is at Appendix 4.

13. The evidence received focused on the changes made by Schedules 2 to 5 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009[1] (the 2009 Act) and in particular changes made by Schedules 2 and 3. A number of general points were also highlighted regarding the judicial appointments process.

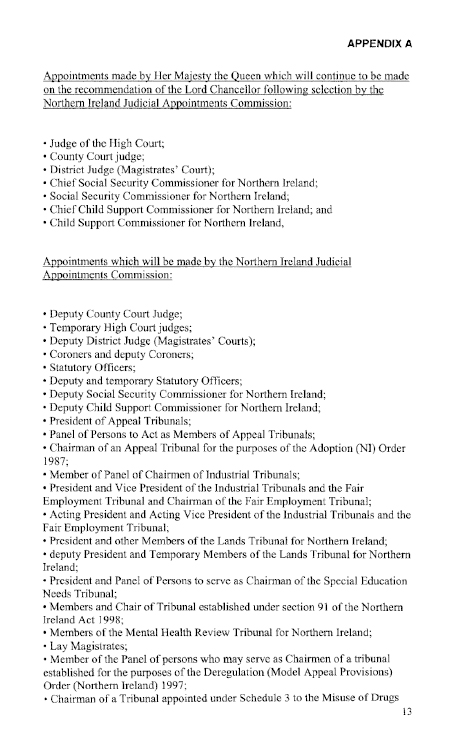

Schedule 2: Substitutes sections 12 to 12C for sections 12 and 12B of the Judicature (Northern Ireland) Act 1978

14. Schedule 2 of the 2009 Act substitutes sections 12 and 12B of the Judicature (Northern Ireland) Act 1978[2] with new sections 12 to 12C. A number of specific points were raised regarding these sections.

Section 12 - Appointment of the Lord Chief Justice and Lords Justice of Appeal

15. Section 12 of the 2009 Act makes provision for the appointment of the Lord Chief Justice and Lords Justice of Appeal by the Queen on the recommendation of the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister must consult the current Lord Chief Justice (or if that office is vacant or the Lord Chief Justice is not available, the senior Lord Justice of Appeal who is available) and NIJAC before making a recommendation.

16. In both his written submission and his oral evidence, the Attorney General highlighted that the appointment of Appeal Judges appeared to have been on a seniority basis rather than through the application of the merit principle and he stated that if the NIJAC system of appointment on merit is considered the most appropriate, there seems to be no clear reason for senior appointments not to be made in accordance with it.

17. The Lord Chief Justice, in his oral evidence as Chairman of NIJAC, offered clarification on this point highlighting that since the 2009 Act there has been a change in the appointment process for Appeal Judges but the new process has not yet been used as no new appointments have been made since the changes came into being. The Lord Chief Justice pointed out that the 2009 Act provides that the Prime Minister has responsibility to make a recommendation for appointment to the Queen and that he must consult with the Lord Chief Justice and NIJAC before making a recommendation. The Lord Chief Justice expressed the view that when the Prime Minister consults NIJAC on the process, given its statutory obligation to pursue all appointments on the basis of merit, it seems inevitable that NIJAC will recommend that the appointment should be on merit and will recommend that there should be a process to ensure that appropriate candidates can participate.

18. In his written submission to the Committee, the Lord Chancellor, the Rt Hon Kenneth Clarke QC MP, drew the Committee's attention to the consultation by the Ministry of Justice on judicial appointments and diversity[3] and highlighted a proposal in the consultation to remove the role of the Prime Minister.

19. The consultation document indicates that historically the Prime Minister has made recommendations to HM Queen for the most senior judicial offices on the advice of the Lord Chancellor. However, now that the Lord Chancellor's role in relation to senior appointments is as a member of the Executive, the consultation puts forward the argument that removing the Prime Minister's role and allowing the Lord Chancellor to make recommendations directly to HM Queen would streamline the process and remove a layer of administration and duplication.

20. The Lord Chancellor indicated that the formal response to the consultation proposals will be available in April 2012.

Section 12C - Removal of Lords Justices of Appeal and also High Court judges

21. Section 12C of the 2009 Act provides for the removal of Lords Justices of Appeal and also High Court judges appointed before section 7 of the 2002 Act[4] (removal from listed judicial offices) came into force. The Queen may remove Lords Justices of Appeal and certain High Court judges following an address of both Houses of Parliament. A motion for an address may be made in the House of Commons only by the Prime Minister and in the House of Lords only by the Lord Chancellor or, if the Lord Chancellor is not a member of that House, only by another Minister of the Crown at the Lord Chancellor's request. No such motion may be made unless a Tribunal convened either by the Lord Chief Justice or the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Ombudsman has recommended that the office holder be removed on grounds of misbehaviour and the Lord Chancellor and the Prime Minister have consulted with the Lord Chief Justice or have been advised by the Lord Chief Justice to accept the recommendation. Pursuant to section 7 of the Justice (NI) Act 2002 the power to remove or suspend a person holding a listed judicial office is now exercisable by the Lord Chief Justice.

22. The Attorney General, in his evidence, highlighted that the limitation in this arrangement is that the address in the House of Commons/House of Lords can only be moved by the Prime Minister or Lord Chancellor and it can be made only if there has been a prior determination by a Tribunal whereas, previously, any MP could have introduced a motion praying for removal.

Schedule 3: Amendments to the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002 amending the appointment and removal provisions

23. Paragraphs 3 and 13 to Schedule 3 of the 2009 Act substitute a new Schedule 3 for Schedule 3 of the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002.

24. A number of specific issues were raised regarding this Schedule.

Process for appointment of those listed judicial office holders by the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Commission

25. Part 2 of Schedule 3 of the 2009 Act sets out the appointment process for listed judicial office holders appointed by NIJAC.

26. The Queen's power to appoint a person to a listed judicial office is exercisable on the recommendation of the Lord Chancellor. NIJAC is responsible for selecting a person for recommendation for appointment and must notify the Lord Chancellor when a person is selected. The Lord Chancellor must, as soon as is reasonably practicable, recommend the selected person for the office. NIJAC select and make recommendations for Crown appointments to the Queen via the Lord Chancellor, up to and including High Court Judges. It is also an appointing body, selecting and appointing persons to non-Crown listed judicial offices.

27. Section 5 and Schedule 3 of the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002 had originally prospectively transferred responsibility from the Lord Chancellor to the First Minister and deputy First Minister, acting jointly, for the appointment of persons and for recommending persons to the Queen for appointment as listed judicial officer holders.

28. Part 1 and Part 2 of the new Schedule 3 no longer include a provision for the Lord Chancellor to ask NIJAC to reconsider their selection. Previously, the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002 provided that when NIJAC made a selection for the Lord Chancellor to consider, he could ask NIJAC to review its choice.

29. Previously, the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002 provided that the power to add or omit listed judicial offices or alter their description was exercisable by the First Minister and deputy First Minister. Section 1 and Schedule 1 of the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2004 amended the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002, transferring these functions from the First Minister and deputy First Minister to the Lord Chancellor.

30. A number of issues were raised in the written and oral evidence regarding the NIJAC selection and appointments process.

The Role of the Judiciary in the Appointment of Judges

31. During the oral evidence sessions the issue of whether the higher judiciary was the dominating element in the NIJAC appointment process was discussed.

32. The Attorney General is of the view that even though the higher judiciary does not form a majority of NIJAC, there is no doubt that, de facto, it is the dominating element.

33. In response, the Lord Chief Justice, as Chairman of NIJAC, outlined that NIJAC was designed to ensure that there was a contribution from the judiciary and from the non-legal members appointed by the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister. He pointed out that the judiciary members understand the nature of the posts and what is expected of the postholders and the lay members are extremely experienced in Human Resources. He indicated that a lay member sits on all competitions and makes as important a contribution as other members and emphasised that all members of the Commission have an equal status and contribute equally to the selection process.

34. Ms Laird, a Lay Commissioner with NIJAC, outlined her role and stressed that the contribution of the Lay Commissioner was no less effective than the judicial members. She indicated that personally she never felt unduly influenced in any direction while on the Commission.

35. In his oral evidence the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Ombudsman stated that if the perception is that judges are appointing judges, it would seem that the whole assumption behind setting up Judicial Appointments Commissions, whether in Northern Ireland, England and Wales or Scotland, is fundamentally flawed as the assumption, when setting up independent Commissions, is that it is about promoting confidence in the way in which judges are being appointed. The Ombudsman suggested that the challenge for any Judicial Appointments Commissioner must be to be able to put across very clearly what the Commission does and how it discharges its responsibilities in seeking, not only to ensure that appointments are being made on merit, but that they deal with the question of diversity and having a judiciary that is reflective of the community in which it is based.

36. In respect of the lay commissioners and the representatives of the legal profession on NIJAC, the Ombudsman pointed out that the challenge is to harness those different perspectives in a way that ensures an appointments system and processes that enjoy confidence and that those skills should also be used in such a way that people, externally, can see and appreciate that.

37. When asked if he felt that the composition of NIJAC should be reviewed, particularly in relation to the number of judicial members, the Ombudsman indicated that the fundamental question is the relationship between the number of people who come from a legal background, not just judges, and the number who come from a non-legal background. In his view, it is not a question simply of the number who sit around a table, it is a question of how to address perceptions that might exist. NIJAC has got to reflect on that challenge. He also indicated that this issue is not unique to Northern Ireland.

The Role of Elected Representatives

38. The Law Society emphasised the fundamental importance of judicial independence. Its position is that the independence of the judicial appointments process underscores the independence of the judiciary and it is of fundamental importance that there is no interference by any member of the Government or Executive. It would therefore be inappropriate for a member of the Executive or Government to be empowered to require a judicial appointments body to refuse or re-consider a recommendation.

39. However, to ensure confidence in the overall appointments process the Law Society states that it is important that there is some form of political accountability for the independence and integrity of the appointments process including the equality of the process that does not compromise operational decision making on individual appointments.

40. The Bar Council strongly endorses an independent judicial appointments process stating that "Sustaining the integrity of the legal system is of supreme importance and any challenge to the independence of the Judiciary or the Bar will ultimately cause harm".

41. The Department of Justice has also pointed out that an effective justice system is a cornerstone of a democratic society and an independent and impartial judiciary is critical to confidence in the administration of justice. The Department notes that the modified arrangements for appointments under the Northern Ireland Act 2009, which were designed to reinforce judicial independence by limiting Executive involvement and which increased the role of NIJAC, must be seen as a positive development and states that it is important that both appointment and tenure are immune from political or partisan interest, in terms of perception and reality.

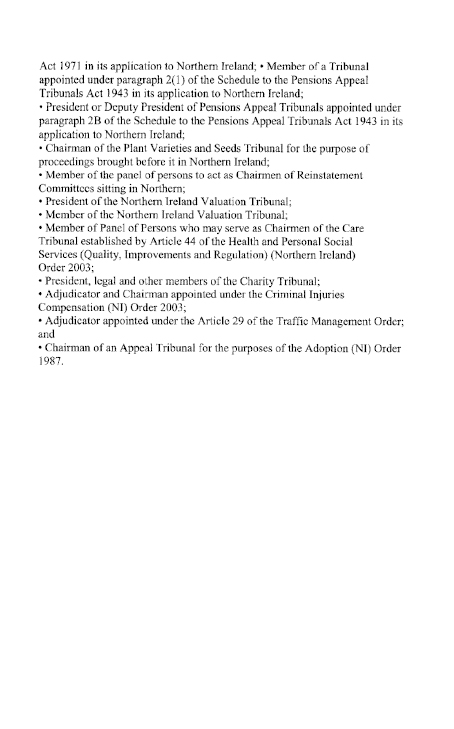

42. The Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) position is that the changes made by the 2009 Act should remain as they are.

43. In his written evidence the Attorney General stated that, on analysis, it may well be that NIJAC is a much less accountable vehicle for appointment than the traditionally politically accountable method. The Attorney General also questioned the transparency of NIJAC, pointing out that it cannot be questioned on the floor of the Assembly regarding appointments.

44. The Attorney General believes that there is a case to explore further ministerial involvement or that of the legislature in judicial appointments and suggests that the Committee for Justice may wish to consider whether it is ultimately healthy in constitutional terms for High Court Judges to be appointed by a Commission dominated by the judiciary as it is at present or whether there should be greater involvement by the Executive and the legislature.

45. He highlighted the views of Sir Thomas Legg QC, in his written evidence to the recent House of Lords Constitution Committee Inquiry into Judicial Appointments[5] when he stated "…. strikes the balance of roles and powers too far towards the judges and too far away from the Executive".

46. When questioned about other possible models the Attorney General highlighted the German model as worthy of scrutiny.

47. In his evidence the Lord Chief Justice highlighted that there has often been some legislative involvement in the appointment of judges and indicated that he had no specific issue with a role for the legislature in the process. He did however question what it would add to a process which is based solely on merit. He also stated that while it might be regarded as unusual for NIJAC to be the appointing body to certain judicial offices as well as having responsibility for selection, as such appointments are more routinely a matter for Ministers, the arrangement appears to have worked perfectly well in practice.

48. The Lord Chief Justice stated that having some legislative involvement is not necessarily contrary to the fundamental principles of judicial independence but all the discussions on this in the UK and elsewhere have not, to his mind, satisfactorily answered the question of what the Executive or the legislature would bring by way of skills to ensure that the process of selection on merit was better achieved.

The selection processes used by NIJAC

49. In its written evidence the Law Society indicated that it would like to see greater acknowledgement in the selection process for skills in drafting legal agreements, the provision of complex legal advice to clients and case/practice management. It stated that it has worked with NIJAC to ensure that the assessment methodologies used in NIJAC competitions take proper account of the expertise and experience of solicitors and to address the view that the judicial appointments process favours the skills and experience of members of the Bar and also disadvantages applicants from a non-public service background.

50. The Bar Council stated that it supports the selection process established by NIJAC. The Bar Council indicated that the recent appointment process for the High Court and County Court demonstrates the work conducted by NIJAC to improve the appointment process in relation to the criteria used, speeding up the process and the confidentiality surrounding it.

51. The Attorney General questioned whether, in relation to the selection process used, the highest score at one or more interviews or exercises is necessarily indicative that the best candidate has been identified. He also expressed the view that it appeared that those who had previous public sector experience were the most comfortable with the NIJAC recruitment method.

52. The Attorney General stated that there needed to be a tailoring of assessment exercises, which may include role play or giving presentations and made the general criticism that a purely competence-based system will not always deliver the best outcome.

53. The Attorney General also raised the question of whether a process could identify several candidates as being worthy of appointment and then have a separate process to identify whether someone has the specific experience that is needed to fill the particular vacancy under consideration.

54. The Lord Chief Justice, in written and oral evidence, outlined the NIJAC appointments process including its use of a generic Judicial Selection Framework which can be tailored to the specific requirements of the judicial office to which an appointment is to be made and how the criteria and the required features for each of the criteria are set. The Lord Chief Justice also indicated that appointment processes had included role play, case studies, presentations, shortlisting tests and published work with the intention of using a broad range of tools to assist the selection process.

55. The Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Ombudsman, in his written submission, indicated that NIJAC should ensure consistency in its approach to competition procedures and appointments.

56. The Ombudsman was also in agreement that there is a perception that judicial appointments are largely the preserve of the Bar.

57. In his oral evidence, the Ombudsman stated that, when selecting on merit, it is about looking at what the criteria and issues are and he indicated that his personal experience on a panel that selects QCs raised, for him, the point that being a very good advocate does not necessarily mean a person will go on to be a very good judge.

Delays in the NIJAC appointment process

58. The Bar Council raised issues about delays in the process in previous selection competitions. Whilst acknowledging that this has been addressed by NIJAC the Bar did highlight that the length of time involved in the confirmation of Crown appointments can have a serious impact on the professional and personal lives of candidates.

59. The Bar Council also highlighted the impact of judicial vacancies on the smooth running of the courts, the current judicial caseloads and the avoidable delay created due to the lack of court time.

60. In response, during his oral evidence, the Lord Chief Justice indicated that the total recruitment time was decreasing.

The Cost of NIJAC

61. In both his written and oral evidence, the Attorney General raised the issue of the cost of the current process for appointing judges and suggested that the process could be handled through the Office of the Lord Chief Justice with the assistance of HR Connect. While moving the responsibility to the Office of the Lord Chief Justice would have some resource implications the Attorney General believed that it could be done much more cheaply as, currently, NIJAC does not run that many competitions in any given year.

62. When this was raised with the Lord Chief Justice, he pointed to the large amount of work carried out by NIJAC to secure a diverse pool of applicants and raised concern that removing NIJAC from the process, while it would not necessarily affect independence, would be a serious departure from the aim of securing the statutory objective of ensuring a diverse and reflective pool of applicants. He also expressed concern that if the selection process fell within his office it could reinforce the false impression that he was in some way in control of appointments with the detrimental effect that might have on public confidence in the judiciary.

63. The Lord Chief Justice also stated out that, unlike HR Connect, NIJAC tailors each competition.

64. The Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Ombudsman, in his written evidence, indicated that NIJAC must take value for money considerations into account and that the selection process should be proportionate but must have a robust audit trail to promote confidence that appointments are being made on merit and in a considered fashion.

Selection or recommendation for appointment to a listed judicial office must be solely on the basis of merit

65. Schedule 3 also provides that selection of a person to be appointed or recommended for appointment to a listed judicial office must be solely on the basis of merit.

66. All respondents to the review supported the principle of selection on the basis of merit.

67. The Bar Council, in its evidence, emphasised that it is imperative that merit is the sole criteria for appointment.

68. The Department of Justice also indicated that any system for judicial appointments and removals is based on selection on merit, through fair and open competition and from the widest range of eligible candidates.

69. NIJAC has outlined that to ensure the merit principle is adhered to and that the appointments process is open and transparent, it has developed a generic Judicial Selection Framework which can be tailored to the specific requirements of the judicial office to which an appointment is to be made.

70. The Attorney General, while raising some questions regarding a lack of understanding of the definition of merit and the process, is supportive of the principle of identifying the best person for the job.

71. The Ombudsman also highlighted that appointments should be strictly on merit and that NIJAC is required, so far as it is reasonably practicable, to secure that a range of persons reflective of the community in Northern Ireland is available for consideration by the Commission whenever it is selecting a person to be appointed, or recommended for appointment.

Judicial appointments are reflective of the community

72. Schedule 3 provides that NIJAC must at all times engage in a programme of action to ensure that, so far as it is reasonably practicable, judicial appointments are reflective of the community in Northern Ireland and that a range of persons reflective of the community are available for consideration by NIJAC when selecting a person or recommending for appointment.

73. The Law Society pointed out that ensuring that the judicial appointments process is open and transparent and takes account of the full range of skills and experiences which make one suitable for judicial office will assist in ensuring a diverse judiciary. It highlighted the findings of the report by the Advisory Panel on Judicial Diversity in England and Wales in 2010[6] and that Baroness Neuberger, the Chairwoman of the Advisory Panel, recently emphasised that encouraging solicitors to apply for judicial appointments is absolutely key to ensuring judicial diversity.

74. The Department of Justice also indicated that the statutory responsibility placed by the 2009 Act on NIJAC to develop a strategy to ensure that persons appointed to listed judicial office and the range of persons available for consideration for selection are reflective of the community in Northern Ireland is to be welcomed.

75. In the view of the Department a judiciary which is visibly reflective of society can only enhance public confidence in the justice system. The Department also noted that research commissioned by NIJAC in 2008[7] on barriers and disincentives to applying for judicial office was largely positive about NIJAC's role.

76. NIJAC highlighted that it has developed a judicial equity monitoring database, plus mechanisms for collating and analysing feedback to inform the judicial appointments process and a robust programme of action to ensure that the Northern Ireland judiciary is reflective of society. It has commissioned research on the matter and undertakes specific tailored outreach and general outreach.

77. During his oral evidence the Lord Chief Justice indicated that, in his view, NIJAC has given a reasonably good account of itself in encouraging a reflective applicant pool and a reflective judiciary. Responding to remarks made by Lord Kerr in his evidence to the House of Lords Constitution Committee Inquiry into Judicial Appointments[8] regarding his disappointment that there was a lack of women on the High Court Bench in Northern Ireland, the Lord Chief Justice outlined that NIJAC was aware that more work needs to be done to encourage applications from women for the higher court tiers. He also expressed his disappointment at the current situation and explained that research is currently being conducted to identify the reasons and how to deal with it. He also pointed out that there is work on-going with the professions to look at the issue and that NIJAC recently visited locations in England and Wales that are looking at alternative working arrangements.

78. The Attorney General, referring to the recommendation by Baroness Neuberger in the 2010 Advisory Panel Report on Judicial Diversity in England and Wales[9], suggested that judicial training for those interested in a career in the judiciary could be considered to encourage applications.

79. In his written submission the Lord Chancellor highlighted that the Ministry of Justice consultation[10] was seeking views on whether the principle of salaried part-time working should be extended to the High Court and above.

80. It is the view of the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Ombudsman that the judiciary should be reflective of the community and seeing judges appointed from a diverse range of non-traditional backgrounds would be seen as a more open-minded approach.

81. The Ombudsman agreed that there has been a perception that the judiciary is not currently reflective of the community in Northern Ireland in respect of gender and believed that this raised questions in relation to what NIJAC can do to enhance confidence, given its statutory responsibility, and how NIJAC goes about making the wider public aware of what it is trying to do in that area.

82. Addressing the question of whether the lack of women in senior judicial posts was due to a cultural mindset the Ombudsman indicated that questions that needed to be explored included are there issues which limit the current pool, how that pool could be expanded e.g. by looking beyond Northern Ireland, are there factors that hold people back from applying such as working practices and opportunities for part-time appointments and the reasons why people are not successful.

83. The Ombudsman pointed out that, in his experience, there is always a time lag between external expectations and changes occurring and, given that Northern Ireland has a relatively small judicial community, the number of opportunities to fill posts are much smaller and any change will probably take longer. He also highlighted that, as an accountability measure, the changes that are expected need to be set out and then the situation monitored.

84. The Ombudsman did not believe this to be an issue only for Northern Ireland and referred to the 2010 Advisory Panel Report[11] as evidence that the Judicial Appointments Commission for England and Wales faced similar challenges in relation, not only to gender, but ethnic background.

Removal of a person from a listed judicial office

85. The new Schedule 3 provides that the power to remove a person from a listed judicial office (or suspend a person from office pending a decision whether to remove him) is exercisable by the Lord Chief Justice upon recommendation by a specially convened tribunal. Previously this power was prospectively provided under the Justice (NI) Act 2002 to the First Minister and deputy First Minister, acting only on the basis of a tribunal recommendation and only on agreement of the Lord Chief Justice. The Lord Chief Justice has discretion not to remove or suspend someone even if a recommendation has been made but must notify the person, the tribunal and, if the tribunal was convened by the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Ombudsman, the Ombudsman of the reasons for not removing or suspending the person.

86. The Department of Justice noted that the changes made to the arrangements for removal from judicial office under the 2009 Act have only been exercised on one occasion since the devolution of justice but indicated that the transfer of responsibility for removals to the Lord Chief Justice afforded additional protection for judicial independence. The Department expressed the view that discipline and removal are properly matters for the Lord Chief Justice as Head of the Judiciary and that the requirement to act on recommendation of a removals tribunal and involvement of the NI Judicial Appointments Ombudsman ensures appropriate checks and balances are in place.

87. The Attorney General indicated in his written evidence that there is no reason why there should not be a restoration of the classic constitutional position, that removal of a judge of the Court of Judicature in Northern Ireland should be possible by Her Majesty only following a resolution of both Houses of Parliament.

Maximum number of persons who may hold a listed judicial office

88. Part 3 of Schedule 3 provides that NIJAC must agree, with the Department of Justice, the maximum number of persons who may hold a listed judicial office at any one time. With the agreement of the Department of Justice, NIJAC may revise this determination.

89. The Attorney General, in his oral evidence, when asked about NIJAC's role in this respect, agreed with the suggestion that it seemed quite extraordinary that an independent and unaccountable body such as NIJAC should determine the number of judges and he was of the view that this was a matter for politically accountable judgments.

90. The Lord Chief Justice clarified that the maximum number of judges is informed by the Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunals Service and that any determination NIJAC makes has to be agreed by the Department of Justice which is perfectly proper as the decision also depends on the Department taking the view that money is available.

91. The Department of Justice indicated that its experience of the 2009 Act arrangements for delivery of the functions has been positive so far.

Other Relevant Issues Raised

92. In addition to the issues specifically relating to the Schedules, the Committee received a number of more general comments about the current Judicial Appointments process.

Sponsoring Department

93. In its written evidence, the TUV proposed that the function of overseeing NIJAC's governance and finance should be passed from the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister to the Department of Justice.

94. During the Attorney General's evidence session this proposal was raised and he agreed with the suggestion that it would not make any real difference in terms of accountability.

95. NIJAC indicated that it has an effective working relationship with its sponsor department in relation to finance and governance, the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister, and the experience of the Department of Justice of the 2009 Act arrangements has been positive thus far.

Tribunals

96. In relation to the Tribunal process the Department of Justice indicated that it is currently considering options for reform of the tribunal system in Northern Ireland, including future arrangements for delivery of functions related to the appointment, removal and terms and conditions of appointment of tribunal members. To help inform the development of proposals the Department recently issued a discussion document seeking views on the current system.

Judicial Appointments Ombudsman – Delivery of Functions

97. The Department of Justice, mindful that only a small number of complaints have been made to the Judicial Appointments Ombudsman since the Office was established (five complaints in five years) and, in light of the Executive Review of Arms-length bodies, is considering possible alternative options for delivery of his functions, including whether it would be appropriate for those functions to be delivered in conjunction with those of another Ombudsman.

98. When asked whether a distinct Judicial Appointments Ombudsman is required, or whether the role could be absorbed into that of a broader Justice Ombudsman, the Ombudsman indicated that it is important that, whatever the mechanism is, it has not only the confidence of the sector that is being investigated but is able to project a sense of confidence to the wider public.

99. The Ombudsman highlighted that soon after his appointment, a comment was made to him that there seemed to have been a lot more concentration and emphasis on policing and prison issues than on the rest of the justice system in Northern Ireland and he expressed the view that if the route of a single Justice Ombudsman was taken it would have to be ensured that he or she gave equal weight to all sections.

100. The Ombudsman also highlighted that the legislation for his role stipulates that he should not be a lawyer nor have sat in a judicial capacity and in his view these are important characteristics.

101. In relation to combining the role with another Ombudsman's role simply because it was another Ombudsman's role, he expressed the view that he was not sure that would be particularly helpful as there is such a wide range of public services. On the other hand, if the role was limited to the justice system, the question is whether that would be sufficient.

Investigation of Complaints in relation to Judicial Office Holders

102. The question of whether the NI Judicial Appointments Ombudsman should have a remit to investigate complaints of conduct against judicial office holders was raised with the Lord Chief Justice who responded that there is a system of complaints in relation to judicial office holders that comes through his office and he is not aware of any sense of public dissatisfaction with the outcome of that process which is managed expeditiously and for virtually no money. He indicated that if there is another process that might achieve better public confidence he would be open to looking at it as long as the factors of affordability and making sure the process will attract public confidence are borne in mind.

103. The Lord Chief Justice confirmed that NIJAC had accepted a recommendation by the Judicial Appointments Ombudsman that the Commission should not make recommendations for appointment in relation to a competition while an individual's complaint about the process is on-going and stated that the Commission has a very positive relationship with the Ombudsman.

104. In his oral evidence the Judicial Appointments Ombudsman outlined that, unlike the Commissioner for Judicial Appointments whose role was prior to his, he is unable to take up thematic complaints, look at wider issues, undertake auditing or take complaints from individuals on behalf of someone else. The legislation clearly sets out that his role is to look at complaints from individuals who have participated in the selection process.

105. When asked if his role could be expanded to deal with complaints of conduct against judicial office holders the Ombudsman indicated that the key question was whether establishing those responsibilities in his office would provide greater confidence in the administration of justice.

Consideration of the Issues

106. Due to the limited time available for the completion of this Review of Judicial Appointments it was not possible to explore the issues in depth and the Committee's deliberations were confined to the issues set out below.

The Role of Elected Representatives

107. One of the issues that was considered during the review was the involvement of Executive Ministers or the Legislature in the Northern Ireland judicial appointments and removals processes.

108. The 2009 Act removed the original intention for the appointment of persons and for recommending persons to the Queen for appointment as listed judicial office holders to be undertaken by the First Minister and deputy First Minister acting jointly. While mindful of the reasons for the current position the Committee notes that the result is that full responsibility now sits with NIJAC and elected representatives play no part in the process.

109. The Committee discussed the question of whether the balance of power in relation to the process for judicial appointments and removals has moved too far towards the judiciary and non-elected bodies and away from politicians. In any further consideration of where power should reside in relation to judicial appointments and to what extent, if any, political representatives should have a role, a distinction should be made between involvement in the selection process and involvement in the appointment process.

Appointment of the Lord Chief Justice and Lords Justice of Appeal

110. Since the 2009 Act there has been a change in the appointment process for Appeal Judges however the new process has not yet been used as no new appointments have been made.

111. One of the criticisms levelled at the previous appointment system is that appointments were based on seniority. The Committee believes that all judicial appointments should be based on merit and is strongly of the view that the merit principle must apply to any appointment process for Appeal Judges or the Lord Chief Justice post. The Committee supports the position of NIJAC, as articulated by its Chairman, the Lord Chief Justice, that, when consulted by the Prime Minister on the appointments process, NIJAC will inevitably recommend that the appointment should be on merit and there should be a process to ensure that appropriate candidates can apply.

Removal of Lords Justices of Appeal and also High Court Judges

112. The Committee notes that a motion for an address can only be made when a tribunal convened either by the Lord Chief Justice or NIJAC has recommended that the officer holder be removed on grounds of misbehaviour and the Lord Chancellor and the Prime Minister have consulted with the Lord Chief Justice or have been advised by the Lord Chief Justice to accept the recommendation.

113. The Committee notes that this is an area where power has shifted from elected representatives.

The Composition of NIJAC

114. The Committee wishes to highlight that there appears to be some perception that NIJAC is dominated by its judicial members. The Committee was struck by the view expressed by the NI Judicial Appointments Ombudsman that the assumption when setting up an independent commission for the appointment of judges is that it is about promoting confidence in the appointment process. While the Committee notes that the Lord Chief Justice, as Chairman of NIJAC, strenuously refutes that the judicial members have more influence and indicated that all members of the Commission have an equal status and contribute fully to the selection process, it agrees with the Judicial Appointments Ombudsman's assertion that NIJAC should reflect on the challenge of addressing any perceptions that might exist.

Judicial Appointments are reflective of the community

115. The Committee is very concerned that, despite the requirement that NIJAC must engage in a programme of action to ensure that so far as it is reasonably practicable judicial appointments are reflective of the community in Northern Ireland, this has not been achieved in the higher court tiers with regard to female representation.

116. The Committee notes that the current Lord Chief Justice has expressed his disappointment about this situation as has Lord Kerr, the previous Lord Chief Justice, in his evidence to the House of Lords Constitution Committee during its recent Inquiry into Judicial Appointments when he outlined his view of the reasons that were acting as a disincentive for women applying.

117. NIJAC, in its evidence, recognised that this is an issue that needs to be addressed and outlined the work it is taking forward, including research to identify the reasons for the lack of representation and what needs to be done to address it.

118. The Committee is disappointed that no progress appears to have been made to address this long standing issue. While recognising that this problem does not just exist in Northern Ireland the Committee is of the view that NIJAC must take forward the work outlined as a matter of urgency and give appropriate priority to it. The Committee would highlight the suggestions that judicial training may be beneficial for those interested in a career in the judiciary and a commitment to flexible working arrangements as worthy of further consideration.

119. The Committee intends to review what progress is made in this area in the future.

Removal of a person from a listed judicial office

120. The Committee notes that the power to remove a person from a listed judicial office is exercisable by the Lord Chief Justice upon recommendation by a specially convened tribunal but the Lord Chief Justice has discretion not to remove or suspend someone.

121. The Committee notes that this is an area where power has shifted from elected representatives.

Maximum number of persons who may hold a listed judicial office

122. The Committee discussed the nature of the current arrangement in which NIJAC plays a key role in deciding the maximum number of persons who may hold a listed judicial office at any one time.

123. The Committee is of the opinion that the fact that NIJAC has responsibility for determining the compliment of judges is unusual and, noting that NIJAC must agree with the Department of Justice the maximum number, would question were the power actually rests in relation to this matter.

Sponsoring Department

124. The Committee notes that NIJAC indicated it has an effective working relationship with the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister in relation to its finance and governance arrangements and the Department of Justice is also positive regarding the delivery of these functions.

125. Given that the arrangements are working well and the First Minister and deputy First Minister also have responsibility for the appointment of Lay Commissioners to NIJAC the Committee sees no reason to change the oversight functions.

Delivery of the Functions of the Judicial Appointments Ombudsman

126. The Committee is aware that the Department of Justice is currently considering alternative options for the delivery of the functions of the NI Judicial Appointments Ombudsman.

127. The Committee recommends that the Department of Justice takes account of the views expressed by the NI Judicial Appointments Ombudsman during his oral evidence to the Committee when reviewing the options and in particular, if consideration is being given to having one Justice Ombudsman, the current legislative requirements that stipulate that the Judicial Appointments Ombudsman appointee should not be a lawyer nor have sat in a judicial capacity.

128. The Committee will give further consideration to this issue when the Department presents its options and findings.

Investigation of complaints in relation to Judicial Officer Holders

129. The Committee discussed the fact that, under the current arrangements, the NI Judicial Ombudsman does not have the power to investigate complaints in relation to judicial office holders (this sits with the Office of the Lord Chief Justice) and his remit under the legislation is very narrow allowing him to only look at complaints from individuals who have participated in the selection process. He is unable to investigate thematic complaints, look at wider issues or deal with complaints from individuals on behalf of someone else.

130. The Committee noted that compared to Judicial Ombudsmen in other jurisdictions the NI Judicial Appointments Ombudsman's role is relatively narrow. This is an issue the Committee may return to in the future.

131. The Committee welcomes the acceptance by NIJAC of the recommendation by the NI Judicial Appointments Ombudsman that it should implement a policy that no formal part of the appointment process to fill a post will be made unless any outstanding complaints process relating to the same competition has been completed. The Committee believes that, in the interest of fairness, this is the correct approach to adopt.

Conclusion

132. Having considered the evidence received and noting that the Department of Justice and the NI Judicial Appointments Commission are of the view that the arrangements created by the 2009 Act, while only in place for a relatively short period of time, appear to be working satisfactorily, the Committee for Justice recommends that there should be no changes to the current process for judicial appointments and removals in Northern Ireland at this time.

133. Given the statutory requirement to report to the Assembly by 30 April 2012 which restricted the time available to complete this review and the fact that a number of issues may merit further consideration, the Committee intends to undertake a further review of the Judicial Appointments and Removals processes.

[1] The Northern Ireland Act 2009. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2009/3/contents

[2] The Judicature (Northern Ireland) Act 1978. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1978/23/contents

[3] Appointments and Diversity, 'A Judiciary for the 21st Century', A Public Consultation. Ministry of Justice

[4] The Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2002/26/contents

[5] House of Lords, Select Committee on the Constitution, Judicial Appointments Process, Oral and Written Evidence.

[6] The Report of the Advisory Panel on Judicial Diversity 2010.

[7] Research into the barriers and disincentives to judicial office by QUB and NISRA. Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Commission.

[8] Lord Justice Etherton, Lord Kerr of Tonaghmore, Her Honour Judge Plumstead and District Judge Tim Jenkins – Oral Evidence to the House of Lords Constiotution Committee. P196

[9] The Report of the Advisory Panel on Judicial Diversity 2010.

[10] Appointments and Diversity, 'A Judiciary for the 21st Century', A Public Consultation. Ministry of Justice

[11] The Report of the Advisory Panel on Judicial Diversity 2010.

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

Thursday 26 January 2012

Room 30, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Givan MLA (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson MLA

Mr Stewart Dickson MLA

Mr Seán Lynch MLA

Mr Alban Maginness MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr Basil McCrea MLA

Mr Peter Weir MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

In Attendance: Mr Paul Carlisle (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Vincent Gribbin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Joe Westland (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Kevin Marks (Clerical Officer)

Apologies:

2.03 p.m The meeting commenced in public session.

11. Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland

Agreed: The Committee agreed to consider the Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland at its meeting on 2 February 2012.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 2 February 2012

Room 30, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Givan MLA (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson MLA

Mr Stewart Dickson MLA

Mr Seán Lynch MLA

Mr Alban Maginness MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr Basil McCrea MLA

Mr Peter Weir MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

In Attendance: Mrs Christine Darrah (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Vincent Gribbin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Joe Westland (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Kevin Marks (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Colum Eastwood MLA

2.02 p.m. The meeting commenced in public session.

1. Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland

The Committee considered draft Terms of Reference for the review of judicial appointments which it is required to complete in accordance with Section 29C of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 as amended by Schedule 6 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009 and Standing Order 49A.

The Committee also considered its approach to carrying out the review and a proposed list of consultees.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the terms of reference for the Review of Judicial Appointments.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the approach to the review should be a targeted consultation with information placed on the Committee webpage.

Agreed: The Committee agreed a list of key consultees from which written evidence will be requested and the commissioning letter to issue.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that arrangements should be made for oral evidence sessions with the NI Judicial Appointments Commission, the Judicial Appointments Ombudsman, the Lord Chief Justice and the Attorney General for Northern Ireland.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 23 February 2012

Room 30, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Givan MLA (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson MLA

Mr Stewart Dickson MLA

Mr Colum Eastwood MLA

Mr Seán Lynch MLA

Mr Alban Maginness MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr Basil McCrea MLA

Mr Peter Weir MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

In Attendance: Mrs Christine Darrah (Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Roisin Donnelly (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Vincent Gribbin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Joe Westland (Clerical Supervisor)

2.04 p.m. The meeting commenced in public session.

7. Update on the Committee's Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland

The Committee note the current position in relation to written evidence received for the Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland and oral evidence sessions scheduled for 1 and 8 March 2012.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 1 March 2012

Room 30, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Givan MLA (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson MLA

Mr Stewart Dickson MLA

Mr Colum Eastwood MLA

Mr Seán Lynch MLA

Mr Alban Maginness MLA

Mr Basil McCrea MLA

Mr Peter Weir MLA

In Attendance: Mrs Christine Darrah (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Vincent Gribbin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Joe Westland (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Kevin Marks (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

2.04 p.m. The meeting commenced in public session.

8. Briefing by the Attorney General for Northern Ireland on the Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland

The Attorney General for Northern Ireland, Mr John Larkin QC, joined the meeting at 3.24 p.m.

The Attorney General briefly outlined his views on the current arrangements for judicial appointments and removals in Northern Ireland.

A question and answer session followed covering issues including the merit principle and how merit is defined; the competence based process and the need for flexibility; the process for appointments to the Court of Appeal; the merits of exploring the possibility of the Legislature having a role in the appointment process; the transparency, cost and accountability of NIJAC; a proposed model involving the Office of the Lord Chief Justice; and models used in America and Germany.

4.02 p.m. Mr Eastwood left the meeting.

The evidence session was recorded by Hansard.

The Chairman thanked the Attorney General for the briefing and he left the meeting.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to commission a research paper on the models used in America and Germany for judicial appointments.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 8 March 2012

Room 30, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Givan MLA (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson MLA

Mr Stewart Dickson MLA

Mr Seán Lynch MLA

Mr Alban Maginness MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr Peter Weir MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

In Attendance: Mrs Christine Darrah (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Vincent Gribbin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Joe Westland (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Kevin Marks (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Colum Eastwood MLA

Mr Basil McCrea MLA

2.02 p.m. The meeting commenced in public session.

9. Briefing by the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Commission on the Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland

The Lord Chief Justice, Sir Declan Morgan, Chairman of the NI Judicial Appointments Commission, Edward Gorringe, Chief Executive, NI Judicial Appointments Commission, Ruth Laird, Lay Commissioner, NI Judicial Appointments Commission and Laurene McAlpine, Principal Private Secretary in the Lord Chief Justice's Office joined the meeting at 2.07 p.m.

The Lord Chief Justice briefly outlined the Commission's views on the current arrangements for Judicial Appointments and Removals in Northern Ireland.

A detailed question and answer session followed covering issues such as the possible impact of moving the work of NIJAC into the Lord Chief Justice's Office with support from HR Connect; the role of the Lay Commissioners in NIJAC and their appointment process; how the merit principle is applied and what it means; the impact of the 2009 Act on how Judges to the Court of Appeal are appointed; the range of processes used in the appointment of judges; what role the Legislature could play in the judicial appointments process; the lack of women representative in senior judicial posts and the reasons for this; the role of the Judicial Appointments Ombudsman in the process; the roles of the Prime Minister and NIJAC in the future appointment of judges to the Court of Appeal; the length of time appointment competitions take; the process for setting the number of judges in Northern Ireland and the current number of High Court vacancies; and what accountability the present system provides.

The evidence session was recorded by Hansard.

The Chairman thanked the Lord Chief Justice and the other representatives and they left the meeting.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 27 March 2012

Room 30, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Givan MLA (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson MLA

Mr Stewart Dickson MLA

Mr Colum Eastwood MLA

Mr Seán Lynch MLA

Mr Alban Maginness MLA

Mr Basil McCrea MLA

Mr Peter Weir MLA

In Attendance: Mrs Christine Darrah (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Vincent Gribbin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Joe Westland (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Kevin Marks (Clerical Officer)

12.36 p.m The meeting commenced in closed session.

1. Apologies

None.

2. Assembly Legal Advice on changes made to the process of judicial appointments by Schedules 2 - 5 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009

12.37 p.m Tara McCaul, Assembly Senior Legal Advisor, joined the meeting.

Ms McCaul outlined the changes made by Schedules 2 - 5 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009 to Judicial Appointments and Removals in Northern Ireland and answered questions.

12.42 p.m Mr Weir joined the meeting.

12.45 p.m Mr Dickson joined the meeting.

12.50 p.m Mr Lynch joined the meeting.

Ms McCaul undertook to provide further advice on an issue raised in relation to the possibility of carrying out a further review in due course.

The Chairman thanked Ms McCaul for her advice and she left the meeting.

3. Briefing on Assembly Research Papers on the Judicial Appointments process in Germany and the United States and the process of appointments to the Court of Appeal in England and Wales

12.58 p.m Fiona O'Connell, Assembly Researcher, joined the meeting.

12.58 p.m. Mr Givan left the meeting.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that Mr Maginness should chair the meeting in the absence of the Chairman and Deputy Chairman.

12.58 p.m. Mr Maginness took the Chair.

Ms O'Connell outlined the key points in two research papers covering the Judicial Appointments process in Germany and the United States and the process of appointments to the Court of Appeal in England and Wales and answered questions on issues such as the role of the legislatures in the appointment of judges in the United States and Germany and the gender imbalance, if any, in other jurisdictions.

1.03 p.m Mr McCartney joined the meeting.

1.14 p.m Mr McCrea joined the meeting.

The Chairman thanked Ms O'Connell for the briefing and she left the meeting.

4. Discussion of the key issues arising from the written and oral evidence received in relation to the Review of Judicial Appointments

The Committee considered a document summarising the key issues arising from the written and oral evidence received in relation to the Review of Judicial Appointments and discussed a number of the issues.

1.29 p.m. Mr Givan rejoined the meeting and took the Chair.

1.29 p.m Mr Lynch left the meeting.

1.32 p.m Mr Weir left the meeting.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that Members should consider the issues further and submit views at the meeting on 29 March 2012.

Mr Paul Givan MLA

Chairman, Committee for Justice

19 April 2012

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 29 March 2012

Room 30, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Givan MLA (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson MLA

Mr Colum Eastwood MLA

Mr Sean Lynch MLA

Mr Alban Maginness MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr Basil McCrea MLA

Mr Peter Weir MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

In Attendance: Mrs Christine Darrah (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Vincent Gribbin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Joe Westland (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Kevin Marks (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Stewart Dickson MLA

2.06 p.m. The meeting commenced in open session

3. Matters Arising

2.07 p.m. Mr McCartney joined the meeting.

2.07 p.m. Mr McCrea joined the meeting.

iii. The Committee considered the summary paper on the Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland and noted a relevant newspaper article and the House of Lords Constitution Committee, report on Judicial Appointments that had just been published.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to discuss their final views on the Review of Judicial Appointments at the meeting on 19 April.

4. Briefing by the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Ombudsman on the Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland

2.17 p.m. The Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Ombudsman, Mr Karamjit Singh, joined the meeting.

Mr Singh briefly outlined his views on the current arrangements for Judicial Appointments and Removals in Northern Ireland based on the complaints that he had dealt with.

2.44 p.m. Mr Wells joined the meeting.

A question and answer session followed covering issues such as whether the Ombudsman's role could be expanded to include the investigation of complaints from the public about the judiciary; whether there needs to be a separate Judicial Appointments Ombudsman or whether the role could be incorporated into a wider Justice Ombudsman; whether the judiciary is reflective of the community in Northern Ireland and what could be done to address the gender and ethnicity imbalances; the perception that the current appointments process is dominated by the judiciary and the legal profession; the time lag between action and resulting changes; the need for any arrangements to provide confidence in the system; and the ombudsman's limited powers and ability to investigate only individual complaints from those who participated in a particular competition.

The evidence session was recorded by Hansard.

The Chairman thanked Mr Singh and he left the meeting.

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 19 April 2012

Room 30, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Givan MLA (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson MLA

Mr Colum Eastwood MLA

Mr Seán Lynch MLA

Mr Alban Maginness MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr Peter Weir MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

In Attendance: Mrs Christine Darrah (Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Roisin Donnelly (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Vincent Gribbin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Joe Westland (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Kevin Marks (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Stewart Dickson MLA

Mr Basil McCrea MLA

2.04pm The meeting commenced. in open session

15. Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland – Consideration of evidence and discussion of final views in relation to findings and any possible recommendations

The Committee noted the legal advice provided in relation to the possibility of carrying out a further review in due course.

The Committee considered the evidence received in relation to the Review of Judicial Appointments and discussed possible findings and recommendations.

4.27pm Mr Weir joined the meeting.

4.36pm Ms McCann left the meeting.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that a draft report outlining the evidence and findings should be prepared for consideration and agreement at the meeting on 26 April.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that a motion to debate the Committee report on the Review of Judicial Appointments in the Plenary should be drafted.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the content of the proposed appendices to the report.

5.01pm The meeting was adjourned.

Mr Paul Givan MLA

Chairman, Committee for Justice

26 April 2012

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 26 April 2012

Room 30, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Givan MLA (Chairman)

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA (Deputy Chairman)

Mr Sydney Anderson MLA

Mr Tom Elliott MLA

Mr Alban Maginness MLA

Ms Jennifer McCann MLA

Mr Patsy McGlone MLA

Mr Peter Weir MLA

In Attendance: Mrs Christine Darrah (Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Roisin Donnelly (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Vincent Gribbin (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Joe Westland (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Kevin Marks (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Stewart Dickson MLA

Mr Sean Lynch MLA

Mr Jim Wells MLA

2.06 p.m. The meeting commenced in closed session.

1. Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland – Consideration of Draft Report

2.10 p.m. Ms McCann joined the meeting.

The Committee considered a draft report on the Review of Judicial Appointments. No amendments were proposed.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to consider and approve the final report later in the meeting.

12. Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland – Formal consideration of Draft Report

The Committee formally agreed the final draft of the Report of the Review of Judicial Appointments in Northern Ireland.

Agreed: that the title page, Committee Membership and Powers, and Table of Contents stands part of the report put and agreed to.

Agreed: that paragraphs 1 to 11 stand part of the Report.

Agreed: that paragraphs 12 to 22 stand part of the Report.

Agreed: that paragraphs 23 to 91 stand part of the Report.

Agreed: that paragraphs 92 to 105 stand part of the Report.

Agreed: that paragraphs 106 to 131 stand part of the Report.

Agreed: that paragraphs 132 to 133 stand part of the Report.

Agreed: that the Appendices stand part of the Report.

Agreed: that the Executive Summary stands part of the Report.

Agreed: that the Chairman approve an extract of the Minutes of Proceedings of today's meeting for inclusion in Appendix 1.

Agreed: that the report on the Review of Judicial Appointments be printed.

The Committee considered the wording of a motion to debate the Report and possible dates for the debate.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the wording of the Committee motion to debate the Report and that the Business Committee should be advised of a preference for 14 or 15 May 2012 for the debate.

The Chairman advised the Committee that the report will be embargoed until the start of the debate.

The Chairman thanked the Committee team for assisting the Committee during its Review and in the production of the Report.

[EXTRACT]

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

1 March 2012

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mr Paul Givan (Chairperson)

Mr Raymond McCartney (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Mr Stewart Dickson

Mr Colum Eastwood

Mr Seán Lynch

Mr Alban Maginness

Mr Basil McCrea

Mr Peter Weir

Witnesses:

|

Mr John Larkin QC |

Attorney General for Northern Ireland |

1. The Chairperson: I welcome the Attorney General for Northern Ireland, Mr John Larkin QC. This session will be recorded by Hansard. If you want to outline briefly your submission, I am sure that members will have some questions for you after that.

2. Mr John Larkin QC (Attorney General for Northern Ireland): Let me thank you formally for asking me to attend today to assist with your deliberations, as the Committee explores the hugely important issue of judicial appointments, particularly the amendments effected by schedules 2 to 5 of the Northern Ireland Act 2009. As always, I am delighted to assist the Committee. Central to my role as Attorney General is upholding the rule of law. It is in that context that I want to make some general comments and observations about what the Committee may wish to consider as part of its review.

3. First, I want to touch on the merit principle. As you know, schedule 3 to the Act continues the statutory requirement that appointments or recommendations for appointment to a listed judicial office be based solely on merit. In one sense, there may be very little that is new in that, because any rational system of appointment should seek to appoint those who are best for the job. A fundamental question about the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Commission (NIJAC) is whether the highest score at one or more interviews or exercises is necessarily indicative that one has identified the best candidate. I note that research commissioned by NIJAC found that few respondents could define merit clearly and that the methodology used to assess candidates was unfamiliar to many applicants. Indeed, it appears that those who had previous public-sector experience were the most comfortable with the NIJAC recruitment method. I understand that NIJAC has put in place arrangements that have enabled the public and the professions to get a better sense of what the judicial world and the judicial role are all about, and it has published questions and model answers to some of its written tests. It has also done useful work in enabling potential applicants for judicial office to better understand judicial life and its implications.

4. Judicial training for those interested in a career in the judiciary might also be considered. That was recommended by Baroness Neuberger in her 2010 advisory panel report on judicial diversity and is useful work. It would be helpful if potential candidates could reflect on whether they were truly suited for the work of a judge; that would allow them to identify and develop, at a pre-appointment stage, the necessary skills that might be prerequisites for judicial appointment. Training is particularly relevant when the candidate at issue is a specialist lawyer and a generalist post is under consideration.