Report on the School Councils Inquiry

Session: 2011/2012

Date: 20 June 2012

Reference: NIA 66/11-15

ISBN: 978-0-339-60438-4

Mandate Number: Mandate 2011/15 First Report

Committee: Education

nia-66-11-15.pdf (5.66 mb)

Committee for Education

Report on the

School Councils Inquiry

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings, Minutes of Evidence and

Written Submissions Relating to the Report

Ordered by the Committee for Education to be printed 20 June 2012

Report: NIA 66/11-15 the Committee for Education

Mandate 2011/15 First Report

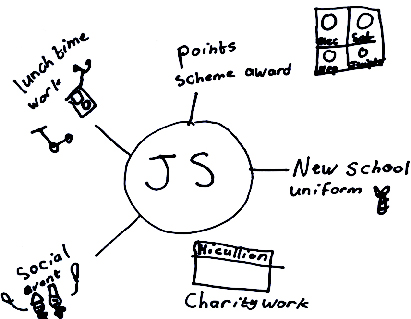

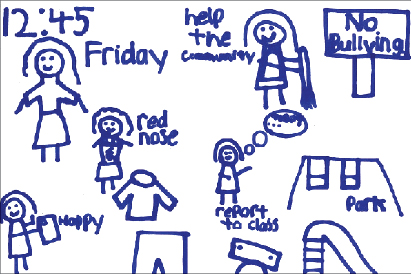

All pictures contained in this report were drawn by pupils as part of the Focus Groups

Membership and Powers

Powers

The Committee for Education is a Statutory Departmental Committee of the Northern Ireland Assembly established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Standing Order 48 of the Northern Ireland Assembly.

The Committee has power to:

- Consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- Consider relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee stage of primary legislation;

- Call for persons and papers;

- Initiate inquires and make reports; and

- Consider and advise on any matters brought to the Committee by the Minister of Education.

Membership

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5. The membership of the Committee is as follows:

- Mervyn Storey (Chairperson)

- Danny Kinahan (Deputy Chairperson)[1] [2]

- Michaela Boyle

- Jonathan Craig

- Jo-Anne Dobson

- Phil Flanagan

- Brenda Hale

- Trevor Lunn

- Michelle McIlveen

- Daithí McKay

- Sean Rogers[3]

[1] With effect from 31 January 2012 Mr Mike Nesbitt replaced Mr David McNarry

[2] With effect from 17 April 2012 Mr Danny Kinahan replaced Mr Mike Nesbitt as Deputy Chairperson

[3] With effect from 23 April 2012 Mr Sean Rogers replaced Mr Conall McDevitt

Table of Contents

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms Used

Key Conclusions and Recommendations

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Appendix 5

List of schools that responded to the questionnaire in relation to School Councils

Appendix 6

List of schools that participated in the Inquiry focus groups

List of Abbreviations used in the Report

ATL - Association of Teachers and Lecturers

DE - The Department of Education

DfEE - Department for Education and Employment

ELB - Education and Library Board

ETI - Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

INTO - Irish National Teachers Association

IPS - Integrated Primary School

NAHT - National Association of Head Teachers

NASUWT - National Association of School Masters/Union of Women Teachers

NCBNI National - Children's Bureau Northern Ireland

NFER - National Foundation for Educational Research

NI - Northern Ireland

NICCY - Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People

NICMA - Northern Ireland Child Minding Association

NYP - NICCY's Youth Panel

Ofsted - Office for Standards in Education, Children's services and Skills

PQH - Professional Qualification for Headship

PS - Primary School

PSE - Personal and Social Education

PSP - Participation Support Programme

SCIE - Social Care Institute for Excellence

SEN - Special Educational Needs

SMG - Senior Management Group

SMT - Senior Management Team

SOAP - Speaking Out Against Poverty Programme

SPSS - a data management and analysis Programme

The Committee - The Committee for Education

The Department - The Department of Education

UNCRC - United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

UTU - Ulster Teachers Union

Executive Summary

School Councils are increasingly a feature of school life all across Northern Ireland and play a key role in many young people's early experience of democratic participation. Research from elsewhere has shown that vibrant, representative and well-resourced School Councils can deliver positive educational and social outcomes to pupils, schools and communities, but that School Councils require support if they are to thrive.

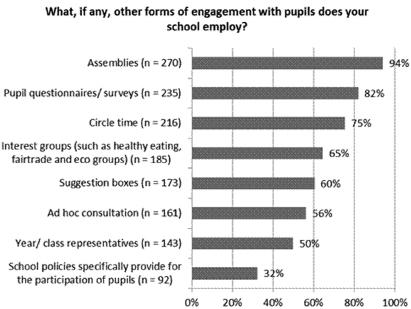

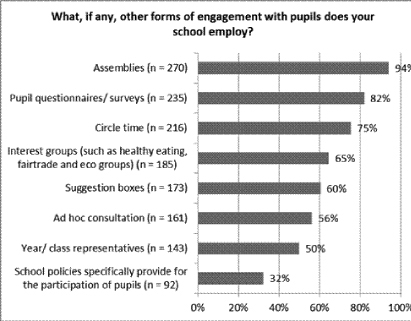

The aim of the Committee's inquiry was to examine the experience, operation and contribution of School Councils in Northern Ireland, with a view to identifying ways to support and enhance their work. The Committee also sought to identify other methods of pupil participation currently in use, as part of this inquiry, with an open mind, as one method may not fit all schools.

The Committee sought to establish a sound evidence base for its scrutiny by taking the views of a representative group of stakeholders and also contacted all schools in Northern Ireland.

The Committee was delighted to see that there are some great examples of School Councils in existence and pupils were very enthusiastic about being part of them and making a difference. The Committee would like to encourage pupils' achievements on School Councils being recognised and celebrated within the school year.

The Committee was encouraged to learn that there is currently 'free' support and guidance from organisations readily available to schools and seeks to encourage the Department to actively promote this resource as well as facilitate the sharing of good practice examples from existing School Councils.

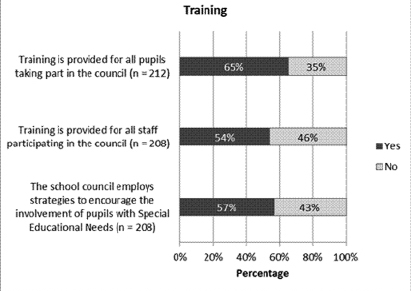

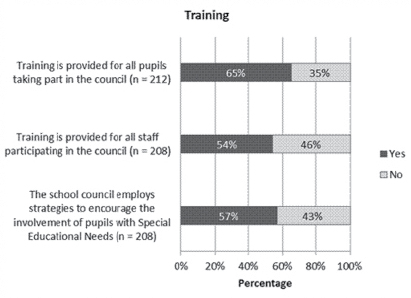

The Committee strongly believes that training and support should be provided for pupils and staff taking part in Councils or other methods of participation, as this will this not only make the participation more effective but will develop life skills for the children taking part; and membership should be rotated to allow opportunities for a wider range of pupils.

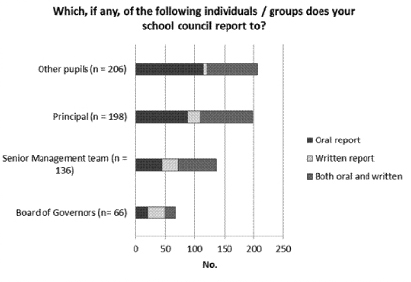

During discussions with the children, it was apparent that the Council should have a say in matters that are central to students' daily life in school. To give purpose and value to the Council, it should report to the school governors on a regular basis.

The Committee is grateful for the contribution of schools, the staff and pupils who participated in the focus groups, stakeholders, Departmental officials and particularly the Assembly Research team and Education Officers, as well as other staff within the Assembly. A number of key conclusions and recommendations have been identified for consideration by the Minister of Education and schools across Northern Ireland.

Throughout this report we have included pictures drawn by pupils who participated in the focus groups, to describe the work and aims of their School Councils.

Introduction

Background[1]

A School Council can be defined as a formal group of pupils within a school who are elected by their peers to represent them and their views. Councils can explore a range of issues affecting young people and for many young people; School Councils are often their first practical experience of democratic values and practices in operation.

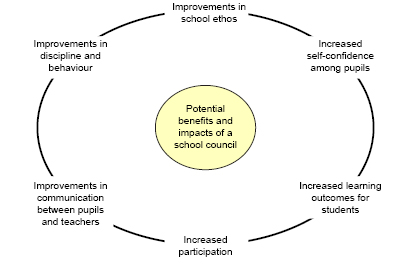

A preliminary review of the research evidence indicates that School Councils have the potential to deliver positive outcomes for students and for schools, including:

- increased self-confidence and learning outcomes for pupils;

- increased participation in school life;

- improvements in discipline and behaviour; and,

- improved school ethos.

However School Councils can face a number of issues, for example a lack of clarity about the Council's purpose, inadequate engagement from staff and the challenge of ensuring representation from pupils of different ages, abilities, disabilities and backgrounds.

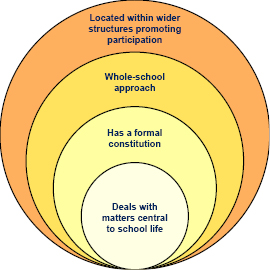

The research evidence also reports that School Councils vary widely in their effectiveness and for Councils to be successful the literature suggests that they must deal with matters central to daily life in school and be situated within wider structures and practices that support participation, mutual respect, co-operation and a commitment to diversity and equality within the school.

Support is available to schools wishing to establish a School Council through the Democra-School programme (produced by the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People (NICCY)). The Department of Education expressed its support for the development of School Councils in all schools. However, it would appear that there is little comprehensive information available on the number of School Councils across Northern Ireland, how they operate and what they deliver. The following terms of reference for the Committee's inquiry into School Councils seek to address this information gap.

Inquiry Aims

The aim of the Committee's inquiry is to champion and celebrate School Councils in Northern Ireland. It will examine the experience, operation and contribution of School Councils in Northern Ireland, with a view to identifying ways to support and enhance their work.

Terms of Reference

At its meeting on 12 September 2011, Members agreed to the following terms of reference for a Committee Inquiry into School Councils.

The Committee wishes to:

- Establish baseline information on the number of School Councils in Northern Ireland;

- Examine how existing School Councils operate in practice;

- Identify what educational and social outcomes School Councils deliver in Northern Ireland and how this compares with reported outcomes elsewhere;

- Make recommendations to support and enhance the work School Councils do across Northern Ireland; and

- Report to the Assembly by September 2012.

At its meeting of 19 October 2011, the Committee formally launched this inquiry.

All pictures contained in this report were drawn by pupils as part of the Focus Groups

The Committee's Approach

The Committee agreed that the inquiry, in the first instance, would be research led rather than focused on gathering public evidence, and would be launched on-line on the Assembly's website. In addition, the Chairperson recorded a short video-piece on the background to, and rationale for, the Committee's inquiry which was placed on a prominent position on the website.

As part of the data gathering phase, all schools across Northern Ireland were provided with an opportunity for School Councils to bring their work to the attention of the Committee.

Literature review

A scoping paper was written by the Assembly Research and Information Service in August 2011 (included at Appendix 3) considering the evidence on the potential benefits of School Councils, issues and challenges around their effective implementation, and the factors and attributes of successful Councils.

Survey

The aim of the quantitative survey was to gather baseline information on the operation and experience of School Councils in Northern Ireland. The evidence within the research scoping paper helped to inform the design of the questionnaire. After piloting, the survey was launched on the 9th January 2012 and sent out to all special, primary and post-primary schools by email via the C2K system.

The survey was sent out to 1,112 schools. A total of 289 responses were received, giving a response rate of 26%. Overall, there was a reasonable spread of respondents across school management type and Education and Library Board (ELB) area.

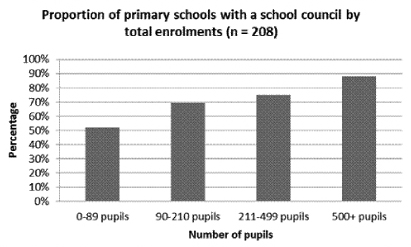

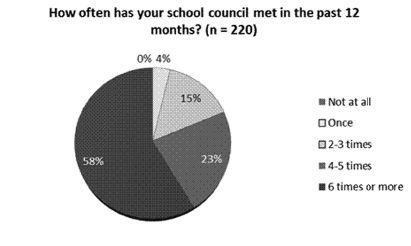

Over three quarters (77%) of respondents to the survey had a School Council. Post-primary schools were significantly more likely to report that they had a Council than primary schools, as were single sex schools (in comparison to mixed schools).

Around 60% of schools responding to the survey, that did not have a Council, reported they were considering or preparing to establish one.

Focus groups

The planned qualitative phase of the research aimed to provide more detailed information on the experiences of pupils taking part in School Councils here, as well as the views of pupils whose school did not have a Council.

Seven focus groups were conducted, 20 different schools, including primary, post primary and special educational needs schools took part, of which five involved participants in School Councils and two involved pupils whose school did not have a Council. The Assembly's Education Officers facilitated the focus groups and Hansard transcribed the sessions.

The children were given an opportunity to voice their opinions and explain the benefits that School Councils can offer.

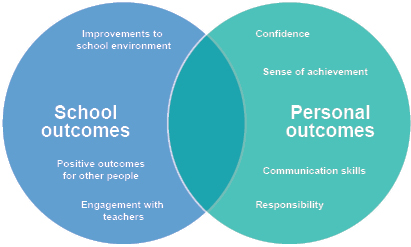

Pupils participating in the focus groups highlighted a range of outcomes from taking part in their School Council. These included personal benefits as well as outcomes for the school, including:

- Greater confidence;

- A sense of achievement;

- Improved communication skills;

- Increased responsibility;

- Improvements to the school environment;

- Positive outcomes for other pupils; and

- Increased engagement with teachers.

In particular, many pupils described a feeling of pride and a sense of achievement as a result of being a school councillor. Increased confidence and greater responsibility were also common themes.

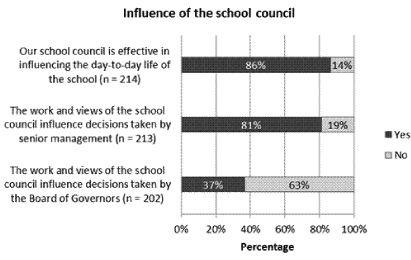

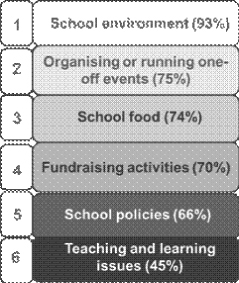

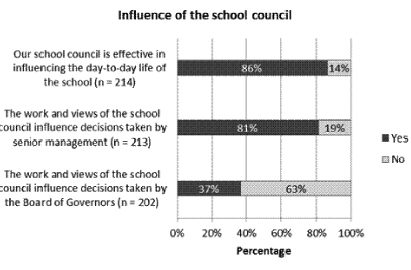

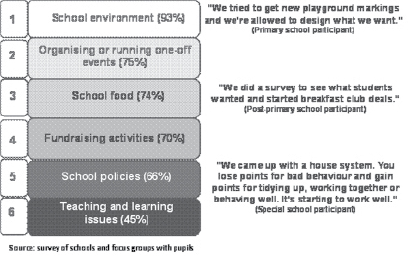

Pupils in the focus groups reported they had most influence in organising one-off events, followed by raising money and school uniform. In comparison, in the survey, the greatest number of respondents indicated that their School Council had most influence on the school environment (93%), followed by organising one-off events (75%).

Many students expressed a preference to 'learn on the job,' however some supported the idea of a forum to share ideas and practice across schools.

A number of pupils highlighted the crucial importance of genuine staff engagement with the Council however, few pupils reported to their school's Board of Governors.

In both the survey and the focus groups, pupils expressed that teaching and learning were the areas in which School Councils had the least influence.

Evidence from both the survey and focus groups suggests that most School Councils have a designated member of staff involved in its work. Many focus group participants reported that this key contact (usually a teacher or vice-principal) took their ideas forward to the principal.

The majority of pupils in the focus groups who did not have a Council stated that they would like their school to have one.

During the focus groups pupils were asked to describe the role of their School Councils, below are samples of the drawings produced at these groups.

Key Conclusions

Pupil participation

The Committee would encourage pupil participation to include reviews, feedback and periodic surveys, to help build upon and improve the mechanisms and relationships within schools.

The Committee observed that Senior Management attitudes to pupil participation varied widely, from a high level of support, resources and participation, to merely paying 'lip service' to setting up a Council and giving pupils no support; the Committee would like to see this addressed within departmental guidelines.

The Committee accepted the views of the pupils it heard from, that thought should be given to the label that is attached to the method of participation chosen by the school; pupils should be allowed to choose the name given to their method of participation, therefore giving them ownership.

The Committee observed that School Councils may not always be the best method for a school to encourage pupil participation, particularly in small schools, and thinks the most important thing is that the Department and schools actively encourage pupil participation and show policy leadership in developing guidelines for this.

Organisational input

The Committee commends organisations such as: the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People (NICCY), Save the Children and the National Children's Bureau N.I. (NCBNI), among others who are undertaking excellent work within schools to assist and encourage pupil participation.

It is apparent to the Committee that a dedicated and enthusiastic member of staff can make a huge difference to the success of a Council. Schools should therefore seek to assign a staff member who will be given the training, time and support to assist pupils in having a successful, meaningful Council of which the school can be proud.

During the focus groups pupils highlighted the fact that structured and clear avenues of communication are crucial. The Committee would endorse this sentiment and ask that schools put in place mechanisms for pupils who are not directly involved in the Council, to both contribute to, and receive feedback on, agenda items and outcomes.

Membership of School Councils

The Committee believes that mechanisms should be developed to encourage pupils with all abilities to participate to avoid 'popular pupil only syndrome'.

The Committee was delighted to see that there are some great examples of School Councils in existence and pupils were very enthusiastic about being part of them and making a difference. The Committee would like to encourage pupils' achievements on School Councils being recognised and celebrated within the school year.

Recommendations

Departmental guidance

The Committee recommends that the Department of Education publicises the 'free' support available, for the establishment and operation of School Councils, from organisations, that is available to schools as well as the online help and guidance.

The Committee recommends that the Department of Education encourages and facilitates the sharing of information among schools of good practice examples, to help develop School Councils, and other methods of participation.

In addition, where School Councils exist within Area Learning Communities, the Department should encourage the formation of a joint Council between the schools in that community.

Training

The Committee recommends that training should be provided for pupils and staff who take part in Councils and other methods of participation, e.g. minute taking, chairing meetings and report writing. This not only makes the participation more effective but develops life skills for those taking part.

Pupil participation

The Committee recommends that the Council should have a say in matters that are central to students' daily life in school.

Membership of School Councils

The Committee recommends that the membership of School Councils should be rotated to allow opportunities for a wider range of pupils.

The role of School Governors

The Committee recommends that all School Councils should report to the school governors; to facilitate this, a dedicated governor should be allocated this duty, or another appropriate formal mechanism put in place.

[1] This section draws in large part on the research paper prepared for the Committee for Education (NIAR 397-11) School Councils, August 2011.

All pictures contained in this report were drawn by pupils as part of the Focus Groups "Happy pupils are the School Council's responsibility." Primary focus

group participant)

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

Wednesday 16 November 2011

Senate, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mervyn Storey MLA (Chairperson)

David McNarry (Deputy Chairperson)

Michaela Boyle MLA

Jo-Ann Dobson MLA

Brenda Hale MLA

Trevor Lunn MLA

Conall McDevitt MLA

Michelle McIlveen MLA

In Attendance: Roisin Fleetham (Assembly Clerk)

Roisin Kelly (Clerk Assistant)

Alyn Hicks (Assistant Clerk)

Paula Best (Clerical Supervisor)

Sharon Young (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Daithí McKay MLA

Phil Flanagan MLA

Jonathan Craig MLA

10.33am The meeting moved into public session.

4. Committee's Inquiry into School Councils - Evidence Session from the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People (NICCY)

11.37am Patricia Lewsley-Mooney, Commissioner, Marlene Kinghan, Head of Communications and Participation and Alison Montgomery, Senior Policy and Research Officer joined the meeting and provided an oral briefing on the work carried out by NICCY to support School Councils and answered Members' questions.

11.47am Mr McDevitt rejoined the meeting.

12.13pm Mrs B Hale left the meeting.

Agreed the Commissioner would accept and consider the correspondence at 3.7 above.

Agreed the Commissioner would provide the Committee with examples of good practice in relation to school councils to assist the Committee's Inquiry.

12.22pm The Chairperson suspended the meeting.

12.33pm The meeting resumed with the Chairperson, Deputy Chairperson, Ms M Boyle, Mrs J Dobson and Mr McDevitt present.

Agreed the Committee Clerk would produce a paper for a possible Committee visit to examine the practice in Wales where school councils are a legislative requirement.

12.34pm Ms M McIlveen joined the meeting.

12.34pm Mrs J Dobson left the meeting.

5. Committee's Inquiry into School Councils – Briefing from the Department of Education

12.34pm Linda Wilson, Director of Parents, Families and Communities and Eve Stewart, Head of Participation and Parenting Team joined the meeting and provided an oral briefing on the Department of Education's position on School Councils and support for pupil participation and answered Members' questions.

Agreed officials agreed to provide the Committee with a copy of its draft guidance on school councils/pupil participation together with a copy of the Minister of Education's letter informing NICCY that it would not progress the guidance until the Committee's Inquiry has been completed.

12.50am Mrs J Dobson rejoined the meeting.

Agreed the Committee would seek the views of the Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI) on school councils and other forms of pupil participation.

Agreed the Committee would ask the Department for its assessment of the costs of operating school councils and other forms of pupil participation.

Agreed the Committee would write to the Department to request details of the schools which allow pupils to review applications for teaching positions.

Agreed the Committee would have one briefing on proposed changes to GCSEs

[EXTRACT}

Wednesday 18 April 2012

Senate, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mervyn Storey MLA (Chairperson)

Danny Kinahan MLA (deputy Chairperson)

Michaela Boyle MLA

Jo-Anne Dobson MLA

Brenda Hale MLA

Trevor Lunn MLA

Conall McDevitt MLA

Michelle McIlveen MLA

In Attendance: Roisin Fleetham (Assembly Clerk)

Sinead Kelly (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Paula Best (Clerical Supervisor)

Sharon Young (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Jonathan Craig MLA

Phil Flannigan MLA

Daithí McKay MLA

10.33am The meeting commenced in open session.

8. NCB Northern Ireland briefing on the Committee's Inquiry into School Councils

12.02pm Celine McStravick, Director and Gill Hassard, Participation Officer joined the meeting and provided the Committee with a briefing on their participation support for schools programme.

12.23pm Mr Lunn left the meeting.

12.29pm Mrs Dobson left the meeting.

12.36pm Mrs Dobson re-joined the meeting.

9. Save the Children briefing on the Committee's Inquiry into School Councils

12.40pm Marie McGrellis,Nicole Breslin and Niamh McGough, ambassadors for Save the Children joined the meeting and provided the Committee with a briefing on School Councils and other ways children can engage and contribute in schools.

Agreed that the ambassadors would provide additional information to the Committee regarding social media and how it is used in a positive way to promote their work.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday 13 June 2012

Senate, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mervyn Storey MLA (Chairperson)

Danny Kinahan MLA (deputy Chairperson)

Michaela Boyle MLA

Jonathan Craig MLA

Phil Flanagan MLA

Brenda Hale MLA

Trevor Lunn MLA

Michelle McIlveen MLA

Daithí McKay MLA

Sean Rogers MLA

In Attendance: Roisin Fleetham (Assembly Clerk)

Hilary Bogle (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Paula Best (Clerical Supervisor)

Sharon Young (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Jo-Anne Dobson MLA

11.05am The meeting commenced in open session.

3. Consideration of the Committee's draft School Councils Inquiry Report

The Committee considered the draft Report section by section.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the papers included in the appendices should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the Executive Summary, as drafted, should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the Background, as drafted, should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the Inquiry Aims, as drafted, should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the Committee Approach, as drafted, should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the Key Conclusions, as drafted, should form part of the Report.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the recommendation on 'Departmental Guidance' should be amended to include reference to areas where there is an existing learning community.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the recommendation on 'The Role of the School Governors' should be amended to include 'or appropriate mechanism put in place'.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the Recommendations, as amended, will be considered again next week.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that a text box should be added to the first page to explain what the pictures are.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that the amendments made today should be incorporated into the final version of the draft Report and included in next week's pack for agreement and sign off.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to launch the Report at an event on 12th September 2012.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to write to the Speaker inviting him to attend the launch and address the audience.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday 20 June 2012

Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mervyn Storey MLA (Chairperson)

Danny Kinahan MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Michaela Boyle MLA

Jonathan Craig MLA

Jo-Anne Dobson MLA

Brenda Hale MLA

Trevor Lunn MLA

Michelle McIlveen MLA

Daithí McKay MLA

Sean Rogers MLA

In Attendance: Roisin Fleetham (Assembly Clerk)

Sheila Mawhinney (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Danielle Saunders (Clerical Supervisor)

Sharon Young (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Phil Flanagan MLA

10.32am The meeting commenced in public session.

6. Committee's consideration of a draft report on its School Councils Inquiry.

The Committee considered a draft of the Executive Summary, the Introduction and the Key Conclusions and Recommendations of the Report on its School Councils Inquiry.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the draft and ordered that it should be published in September 2012.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday 4 July 2012

Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mervyn Storey MLA (Chairperson)

Danny Kinahan MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Michaela Boyle MLA

Phil Flanagan MLA

Trevor Lunn MLA

Michelle McIlveen MLA

Sean Rogers MLA

In Attendance: Roisin Fleetham (Assembly Clerk)

Sheila Mawhinney (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Paula Best (Clerical Supervisor)

Antoinette Hoskins (Clerical Officer)

Simon Kelly (Assembly Legal Service) (Item 1 only)

Kiera McDonald (Assembly Legal Service) (Item 1 only)

Caroline Perry (Assembly Research and Information Service) (Item 6 only)

Apologies: Jonathan Craig MLA

Jo-Anne Dobson MLA

Brenda Hale MLA

Daithí McKay MLA

10.50 am The meeting moved into public session.

Chairpersons Business

- The Committee considered amendments to the report on its inquiry into Schools Councils.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that these amendments should be added to the final report for publication.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that a relevant extract of the minutes of this meeting should be approved by the Chairperson and included in the report.

[EXTRACT]

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

16 November 2011

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mr Mervyn Storey (Chairperson)

Mr David McNarry (Deputy Chairperson)

Ms Michaela Boyle

Mrs Jo-Anne Dobson

Mrs Brenda Hale

Mr Conall McDevitt

Witnesses:

|

Mrs Patricia Lewsley-Mooney |

Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People |

|

|

Mrs Marlene Kinghan |

Office of the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People |

1. The Chairperson: Patricia, you are very welcome and it is good to see you all again. Our apologies for the delay; we overran badly in dealing with our correspondence. Thank you for the information that you have supplied to us. An issue was raised earlier in the meeting about a particular child and parent. We will forward you a copy of the letter.

2. Mrs Patricia Lewsley-Mooney (Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People): I already have a copy of it. I will pass it to my legal and casework team, which will correspond with the parent.

3. The Chairperson: Let me say to members that I have noticed that, on a number of recent visits to schools, it is interesting that many schools have included their school councils. Last week, we met the school council at Harberton Special School, which was very interesting. So this is a timely piece of work. I hand over to you, Patricia.

4. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Thank you very much, Mr Chairman. Let me first apologise; I have a bit of a cold. I hope that I do not start coughing in the middle of the presentation.

5. The Chairperson: If it is only like this, that will be all right.

6. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: I think that you are far enough away.

7. I would like to begin by thanking the Committee for its invitation to attend. I am delighted to share details of the work that I have undertaken to promote and support democratic structures for participation in schools.

8. I warmly welcome the Committee's inquiry and its intention to take account of schools' experience of school councils and the contribution that such councils have made to school life and pupils' personal, social and educational development.

9. In this short presentation, I will highlight the key issues outlined in my written submission to the Committee, to which the Chairman has already referred. It will include some reference to relevant policies in international obligations which support school councils and democratic structures and a description of our Democra-School programme and feedback from schools. I will also outline what I feel needs to happen to take the issue forward and how the Committee, through its inquiry, can make the most impact for children and young people.

10. By way of introduction, I want to say that my office has been working on school councils and democratic structures in schools for more than six years. That issue was first brought to the attention of the previous commissioner in 2005, and since then the office has undertaken research on the issue, worked with schools to support the establishment of school councils, gathered feedback from schools and engaged with a range of key stakeholders. Over that time, we have moved from research to practice to seek to influence policy. Indeed, we were working with the Department to develop policy guidance on school councils and were informed by Department officials that that was in draft in February 2011. Sadly, we were informed late yesterday afternoon that the Department has decided to await the outcome of this inquiry before progressing with the guidance. Therefore, while I believe that the inquiry is vital, it is important that the Committee is aware of the progress that has been made in supporting school councils and democratic structures and in drafting policy guidance, and it would, therefore, be deeply concerning if the work that has been done by teachers, pupils, previous Ministers and others over the past six years was lost.

11. I will outline the relevance of my powers and duties on school councils. I have a mandate to keep under review the adequacy and effectiveness of practice relating to the rights and best interests of children and young people by relevant authorities. Practice here includes what happens in schools and, therefore, relates to the opportunities that pupils are given to participate and to contribute their views.

12. Before I talk about school councils, it is important to say that although they are generally recognised as the most common means of involving pupils in decision-making, there are other forms of democratic representation in schools. One size does not fit all. For example, schools can identify class, form or year-group representatives to collect and communicate pupils' views to the senior management team in a school. Pupils may also be asked, through questionnaires or class consultations, about their views on issues that affect them. I am supportive of the different democratic structures in schools as long as they can meaningfully and effectively involve pupils. Research indicates that pupils overwhelmingly want to be involved in participative decision-making in schools. However, while they are likely to take a lead role in the running of the school council, it is vital, if it is to be successful, that everyone in the school community is committed to, and willing to play their part in, the operation.

13. It is important to highlight the relevance of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) to the development of school councils. Article 12 of the convention enshrines the right of the child to have his or her views heard, listened to and taken seriously, and, by ratifying the UNCRC, the Government have an obligation to protect that right. Furthermore, in its concluding observations on the implementation of the UNCRC in the UK, the United Nations committee recommended that the Government strengthen children's participation in all school, classroom and learning matters that affect them.

14. The importance of listening to children and seeking their views on matters that affect them is emphasised in various government policies and strategies, including the 10-year strategy for children and young people in Northern Ireland 2006-2016 and the Education and Libraries (Northern Ireland) Order 2003. Moreover, guidance that relates to school development planning, which supports the Education (Northern Ireland) Order 1998, states:

"The quality and value of pupils' contribution to improving the life of the school is potentially very great, even among the younger children. It is dependent on the extent to which the Principal and staff are able to create opportunities and the climate for constructive and positive debate."

15. It goes on to suggest that consultation can be organised in a variety of ways, including through the establishment of a school council. So, there is recognition by government of the importance of children and young people participating in decision-making and of the potential value of their contributions. That is encouraging, but we need to go further.

16. I will introduce Democra-School, and I hope that members have a copy of the resource. Democra-School was compiled by my office in partnership with teachers and pupils. It is guidance that also contains a set of standards, and it aims to help schools to establish and sustain school councils and democratic structures.

17. The decision to develop Democra-School arose from our awareness of the lack, or the inconsistent use, of participatory procedures and policies. Such procedures and policies are ways by which pupils can have a say in the school. Even were such structures existed, they were sometimes just tokenistic, were not taken seriously or were not managed effectively by staff. Pupils contacted the previous commissioner to raise concern about the issue. Teachers emphasised the benefits of school councils but were disappointed by the lack of guidance.

18. Democra-School was developed with the support of a steering committee that was set up in 2005. Discussions were also held with Angela Smith, the then direct rule Minister of Education. She encouraged the project and was supportive of having a policy for school councils. In 2006-07, two major conferences of pupils and teachers were convened, and the information exchanged at them on the positive and negative practices was used to compile Democra-School guidance and standards.

19. Each section of the guidance identifies a key issue which pupils, teachers and other stakeholders recognised as important in the development of a school council. The guidance explores why the issue is significant and suggests how a school might think about how to address it. A simple checklist provides a reminder of different tasks that should be completed to achieve a standard. Throughout the document additional information and resources are signposted, and schools are encouraged to explore those.

20. Democra-School is designed to support schools at each stage of the journey from a school council's creation, through its development to evaluation and review. It takes a step-by-step approach that recognises that each school is unique, with its own particular strengths and requirements, and the resource is endorsed by School Councils UK. Following the conferences, my staff delivered additional workshops and training, and ongoing support is being delivered to schools that are interested in the Democra-School programme.

21. During autumn 2010, 20 schools that participated in the first Democra-School workshops were asked to complete a survey to review their experiences of having a school council. Pupils and teachers commented on many positive outcomes, which included council members becoming more confident, particularly in public speaking and decision-making; improved teaching in schools, because the school council was consulted about teaching tools or methods; and pupils having a more positive attitude to school because they felt more involved in decision-making.

22. Schools also reported that there was better communication between teachers and pupils. Teachers felt that pupils accessed and understood information more effectively when it was communicated through the school council rather than during school assembly or via class announcements.

23. There were also some challenges. A number of schools reported that it was difficult to find an appropriate time to meet. That was a particular challenge in rural schools, where pupils had to travel some distance home. Other schools mentioned difficulties in finding a suitable time to meet the board of governors, adding that delays in arranging such meetings could lead to delays in decision-making. Many potential initiatives identified by school councils required additional funding that was not always available, although some councils were involved in fund-raising activities. Managing pupils' expectations was a challenge for some pupils who were not always fully aware of a school council's remit, and council members sometimes felt under pressure to deliver outcomes or to bring about change.

24. Although the consultation was not extensive, responses indicated that the positive outcomes far outweighed any challenges. However, it is important to acknowledge that those challenges exist. As the Committee noted, there is an absence of data in relation to school councils in Northern Ireland, and I am pleased that the Committee plans to collate more complete and accurate statistics. Doing so is essential to the setting of a benchmark.

25. As I said, my staff and I have engaged on the subject of school councils with a range of key stakeholders, including representatives from the five main teaching unions, school principals and academics from the school of education at Queen's University. We explored their views and experiences of school councils and discussed what they felt that the Department of Education's role should be in promoting and supporting school councils and democratic structures. Union representatives expressed their support, in principle, for the Democra-School programme. They also indicated their willingness to support schools in establishing school councils.

26. When I first considered how school councils might be more widely promoted, I considered ways of amending the draft Education and Skills Authority (ESA) legislation. Members may be aware that legislation relating to school councils was introduced in Wales in 2005. However, following discussions with the then Education Minister, Caitríona Ruane, I decided that it would be more expedient to work collaboratively with the Department of Education to support the development of policy guidance for school councils. The Department endorsed Democra-School guidance on its website in 2009. It also made reference to the role, benefits and usefulness of school councils in many policies, circulars and reports.

27. My staff and I have participated in ongoing discussions with various Education Ministers and Department officials since 2005. In 2010, the Department expressed its commitment to move the process forward and requested that we provided information about what should be included in policy guidance for school councils and democratic structures. In February 2011, the Department confirmed that a draft circular of that guidance had been prepared for internal consultation. However, that was delayed due to the Assembly elections. Just late yesterday afternoon, I learned that the Department has now decided to further delay producing guidance, as it wishes to await the outcome of your inquiry.

28. Since the issue was raised with us, we have been working in a variety of ways to support the establishment, development and sustainability of school councils or alternative democratic structures. A timeline detailing our work is included with our written submission. My decision to work with the Department was, essentially, a compromise. I made that decision because I believed that that approach would enable pupils to access participation opportunities in their schools more quickly. I am, therefore, extremely disappointed by the Department's delay in producing policy guidance and the Minister's recent decision to postpone this again.

29. The Department has made many references in legislation, policies, reports and on its website to the benefits and importance of school councils and democratic structures. Despite that, it is not now going to provide schools with the appropriate departmental guidance to support them in developing democratic structures. I urge the Committee to call on the Department to produce the guidance for schools and to give consideration to the development of a policy on school councils. Introducing a policy would ensure that every pupil has the opportunity to participate in decision-making in their school. That protects children's right to participate as enshrined in article 12 of the UNCRC. It would also identify appropriate standards, which would seek to ensure consistency and quality in provision across schools. Crucially, it will also provide a means by which that could be monitored and evaluated.

30. I welcome the Committee's inquiry and believe that it will generate valuable quantitative and qualitative information. I sincerely hope, however, that come next September I will be joining the Committee in not only celebrating the best practice of school councils and other democratic structures but also welcoming the introduction of policy guidance for schools.

31. The Chairperson: Thank you very much, Patricia. The information that you have provided to us has been a huge help. We are not starting here with a clean sheet. You have done a huge amount of work, such as the process that you have engaged in, the information and analysis, and the audit that you carried out in 2010 that showed that fewer than 15% of schools have a school council. It will be interesting to see whether that has changed.

32. I will put this question to departmental officials when they come in. If the Department has postponed what it was supposedly producing, it might be good if the officials would even share with us at least what their starting baseline was. That would then help us in trying to develop and make proposals. That would be a different way to approach the policy agenda, rather than the Department always producing a policy and us scrutinising it. If there was collaboration between us and them, we may get better guidelines coming out the other end.

33. What do you see, Patricia, as the core problem in the legislative sweep from the convention to the Education and Libraries (Northern Ireland) 2003 Order? If you were in a position to do so, what would you say needs to be done legislatively to really help the process of the introduction of school councils?

34. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Importantly, it is not about creating a separate piece of legislation. It could be easily added to some of the education legislation that is coming up the line. For instance, when we looked at how it could be added to the ESA legislation, we were told that that could not be done because it would need to go out for consultation. The compromise for us was that, if we at least got policy guidelines, there would be a hope that it would eventually move further down the line and be added to education legislation somewhere else rather than go through the House as a separate piece of legislation.

35. It is disappointing for us. The compromise at that time was to look at the policy guidelines. We had hoped that those would come to fruition and be put into use in January 2012. We have been delayed and delayed and delayed. The young people who have been involved in this process since 2005 were continually given support and promises, and they thought that it would happen. They have now left the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People's (NICCY) youth panel and come out of university, and they are saying, "Still nothing has happened. What kind of Government does not listen to the voice of young people?" That makes it very difficult.

36. The Chairperson: In the paper that you gave us, you mentioned the survey that was carried out. One principal made the interesting comment that school councils contributed to improving both teaching and learning. Is that a commonly held view, or do some teachers and management structures see school councils as an unwelcome interference in how they should best run the school?

37. Mrs Marlene Kinghan (Office of the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People): As Patricia said, feedback on the work that we have done since 2005 has been very positive, not just from children and young people but from teachers in particular. Most teachers probably do a lot of this every day. To be fair to the teachers, they do not cause the sticking point. It becomes a bit of a sticking point when they perhaps need a certain type of resource or a change in the timetable. This is not all about resources. Sometimes it may be just about changing the school timetable to alleviate one duty of a teacher to enable him or her to take on some of this work.

38. There were some problems around the lack of a constitution, proper guidance on how this would work and a system in which they could feed back and monitor and evaluate it. That is very important in respect of performance nowadays. Those are all issues that teachers felt would be well captured if they had some sort of policy. However, with the best will in the world, it is very difficult for a teacher to put those proposals forward in the absence of that policy. They cannot feed back as they would want and, at that point, may decide to come back to it another day. The will of the teachers and the unions back that up; the unions very much backed that up when we met them.

39. The Chairperson: Marlene, did you or the organisation envisage the guidelines being about how the Department sees school councils operating? Or, were the guidelines more about helping pupils and teachers by setting out how school councils could be established or managed? Did you see the guidelines as being all-encompassing?

40. If all these things emanate from the bowels of Rathgael House or wherever, there can be a one-track approach. However, school councils are a two-way process. They are primarily about listening to the voice of young people, but they are also about ensuing that that structure is in place. It is a two-way process in which both sides of the debate should have an understanding of what is expected of them in a general framework.

41. Mrs Kinghan: From talking to the people who know about this — teachers, principals, pupils and officials — we know that it is a three-way process. The overwhelming feedback that we got is that it will only work if everyone, including the Department, officials and boards, gets involved and backs it. When we did the initial work, rather than lobbing for legislation or putting forward proposals for policy, we brought together a steering committee of interested parties. Those interested parties included principals who had worked in schools in which there had been bullying, graffiti, issues with pupil behaviour and issues between pupils and teachers, which created absenteeism and all sorts of other issues. When they came to us and said that they had an example of how they were able to get over some of those hurdles by involving the pupils, in consultation with the teachers, and moving this forward, they said that they were converts, wanted to tell others and asked if they could come onto the steering committee. We had very little difficulty in getting people to join; in fact, we were oversubscribed. When we ran the conferences, we had to put a limit on those who could attend the workshops. For us, it was clear that there was a major impetus out there.

42. We involved the Department by asking its officials to sit on the steering committee. We got representatives from the citizenship programmes of each of the five education and library boards. That was very useful, and it fitted in very well to their areas of work. From our point of view, it was a win-win situation for all three, particularly for the schools which had to move this forward and, ultimately, develop young people to become active citizens and to take their part in a democratic society.

43. Dr Alison Montgomery (Office of the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People): We provided substantial support to the Department in developing guidance. There were a number of issues to look at. First, we gave teachers the context of why this is important and how it is relevant to other departmental policies, strategies and so on. We also looked at the role of the council. We suggested that it was important to be clear about what the role of the council was within the school. It is also important to look at the key features of what makes effective school councils. In putting that information together, we pulled together information, advice and so on that we had been given from teacher unions, teachers and pupils.

44. We also looked at the role of different educational stakeholders and took them through the process of how a school council operates from the beginning, through its development to its evaluation and review. We also looked at positive examples of how you engage with pupils in the community and, obviously, referenced the benefits to that.

45. It was a very holistic type of input, and we talked it through in a lot of detail with the Department. The school council has to be supportive, and you have to be able to demonstrate how it has had a positive impact. It is also important to put it in the context of wider educational policy and legislation.

46. Mrs Dobson: Thank you for your presentation. It is a relevant and important issue, and it is great that you are presenting to the Committee on it. I share your views on the protection of children's rights. That is an incredibly important issue. It is important that they are protected not only on paper, but in reality. I believe that school councils have the potential to play a major role in that protection.

47. I have a couple of questions, and my first follows on from points that Marlene made. What steps do you believe principals and teachers should take to ensure that, once set up, the school council retains members and actively encourages their participation on a range of issues across the school?

48. Secondly, I notice that public speaking improvements were noted by participants. That is extremely important, and it is brilliant to hear. Have you made contact with the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists on that issue, as it may have interest in such improvements?

49. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Your first question relates to the commitment of principals to school councils in the first place and how they are set up. Having the policy, guidance and standards in our packs was important to us. We want to have a standard of school council across the board. We have been to a number of schools, and we have seen cases where there has been a great use of school councils and where they have bedded into the schools and others where, as a token gesture, they meet once a term. We have also seen schools that do not agree with school councils. We have to get the message across. Sometimes we have brought those groups of people together to talk about how they can do that. Some of the young people who are involved in school councils have created forums of school councils that come together to talk about the issues that they look at and about how they can share some of their skills and experiences.

50. Mrs Dobson: Is that involvement retained and maintained through young people telling other young people? How would you encourage them to keep it going and encourage participation once it is set up?

51. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: The issue is the culture within the school and how it encourages young people to get involved. Very often, we hear about the great and the good always being picked for things, but we have found that a school council provides an opportunity for young people who normally would not get involved in things. As I said, I have been to schools where the whole process of the election has even been there, and young people who want to stand for election create manifestos and go out and sell what they would do for the class. So, you could have three or four people in the one class going for one position. That process leads to pupils getting their voting slips two weeks before the vote is to take place — if you do not have your voting slip you do not get to vote — to doing PR and going upstairs to the sixth form room where the pupils are counting the vote. The announcement of the election is later down the line.

52. Mrs Dobson: We saw a vote in Limavady, and it was brilliant.

53. The Chairperson: The day that we were in Limavady, they were voting.

54. Mrs Dobson: The atmosphere was brilliant.

55. The Chairperson: The members tried to vote, but they could not produce identification, so they were not allowed to.

56. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: So, the issue is the culture within the school and how young people are encouraged. The more young people go forward, the more they are encouraged to go forward.

57. As I said, we have seen the positive outcome from school councils, such as the public speaking aspect, confidence building and self esteem. Having a voice that somebody listens to builds young people's confidence.

58. Mrs Kinghan: Just to add to that, it is about building momentum and retention. That is where the standards come in. The standards include such things as getting the school's board of governors on board and getting the whole school environment involved.

59. Mrs Dobson: That is how you keep the momentum.

60. Mrs Kinghan: Exactly. It is an issue of winning hearts and minds. It is like anything we try to do: you can legislate all you want, but, at the end of the day, you have to win the hearts and minds. That was the big issue here. There were a lot of hearts and minds, but there were some people in the organisation saying that it would be too difficult. There are barriers and challenges, and we recognise that, but, keeping the impetus going requires leadership from the top. Having these standards and being able to support the board of governors to give it guidance on how to approach this is important, because it is not something that everybody may know about. This is useful for them.

61. The issue is also about making sure that the standards are in place and that people and pupils know the expectations, because there can be an issue of raising expectations beyond what the school can deliver. So, that very honest conversation needs to take place, and that would be built into the standards that, hopefully, they would be able to get out of it.

62. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Your second question was about the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. We have a very good working relationship with that organisation, particularly in working together on speech and language services. I do not know whether we have ever asked them the specific question about school councils.

63. Mrs Kinghan: One of the very positive things in this has been the work that we have done in special schools. So, there has been speech and language involvement there. People may think that you cannot have a school council in a special school, but very much the opposite is true. Again, we were inundated with responses from special schools with fantastic schools councils, and we were delighted to see that there were so many.

64. The Chairperson: Harberton Special School was amazing.

65. Dr Montgomery: You will see from our audit that 10 special schools indicated that they had school councils.

66. The Chairperson: I saw that.

67. Have you ever had an example of a school council that sent a representative to the board of governors?

68. Dr Montgomery: There is a mechanism whereby pupils can go forward to represent the views of the school council to the board of governors. That works in a more organised fashion in Ireland and in other jurisdictions, but it has happened in some schools in Northern Ireland, where pupils from student councils have gone forward to represent a view on a particular issue to feed in to the school governors' decision-making. So, that is quite an effective mechanism.

69. Mrs Dobson: Have organisations, such as the Scouts Association or the Girl Guides, been in touch with you about providing badges or certificates of achievement through the school council? Is that a way of rewarding children that you could explore at some point?

70. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Not through the school councils. However, we have worked with uniformed organisations around a number of things, including workshops. We are working on a badge to do with the UNCRC that some of the uniformed organisations could obtain. It has been done already in Wales and other places, so we do not want to reinvent the wheel.

71. Mrs Dobson: None of them have approached you through the school councils yet?

72. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Not through the school councils in particular, but we work directly with the uniformed organisations, such as the Boys' Brigade and others.

73. Mr McNarry: You are welcome. I was interested in your presentation. It was genuinely caring and certainly very knowledgeable. If you do not mind me saying so, it was robust where it needed to be. However, it was the robust bit that I picked up on, as I naturally would. Just to get it clear in my head, did you infer or say that the Department delayed policy guidance, awaiting the outcome of our inquiry?

74. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Yes. The Department sent me an e-mail late yesterday afternoon. I do not have a hard copy of the letter yet, and I will take it up with the Minister. However, I received an e-mail late yesterday afternoon, which said that it would not be continuing with the guidance until the inquiry had done its work.

75. Mr McNarry: It is rather flattering but, at the same time, I assume it is a cop-out.

76. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: There could have been a parallel process. The work on the guidance could have continued, and the Committee could have carried out its inquiry. As you said, Mr Chairman, you could have encompassed it. In fact, as you said from the outset, it might have helped you in some of your decision-making.

77. The Chairperson: There will be an opportunity to put that to departmental officials in a few moments.

78. Mr McNarry: It is always very interesting when someone else appears to know more than we do. I am inquisitive about how they know that and what else they know. Are you telling the Committee that the Department has prepared some papers but that it has put them on hold and, perhaps, it would be a good idea for the Committee to get a hold of them?

79. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Yes. That is what the Chairman was saying earlier. We were told in February this year that the draft guidelines had been produced but that they had to go to officials and the Minister.

80. Mr McNarry: I wanted to hear that a second time. I just wanted to be sure that that is where we are.

81. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: We then had the elections in the middle of that, which put it on hold for another while. However, we met the Minister, and we raised the issue of the guidelines, and he kind of said that it was not as big a priority as it might have been for the previous Minister but that it was still ongoing. Then we got the letter yesterday to say otherwise.

82. Mr McNarry: May I go on to a separate point? I understand that the commission played a role when, I assume, it was asked to by schools that are facing the threat of closure. Did any of those schools have a school council involved in that approach to the commission?

83. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: We have been approached by a number of parents and others about a number of closures. I cannot really talk about individual cases or schools. However, my legal and casework team is looking at that. As far as I am aware, no young people have come forward. It has been the parents and some of the adults concerned.

84. Mr McNarry: I know that you cannot talk about individual schools, and I would not want you to. Without mentioning any names, I have one such school in my own consistency, and that is how I know about it. Are you able to give us details on the role that you do play when such contact is made? Keeping in the context of what we are discussing, would school councils have a role to play in, at least, having an opinion on the issue that their school might be closed? An awful lot of schools will be feeling the threat. I am wondering whether school councils could get involved when there is a threat to their school or even a threat to their neighbours.

85. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: There is certainly an opportunity for the voice of young people, whether they are in a school council, in a school that is threatened with closure, or they want to support children who attend a school that is threatened with closure. Very often in such debates, however, those are the last voices to be heard. We have a role in several ways; I will give you a short example of one way in which we have become involved. We will be seeking legal opinion, in light of the Minister's ongoing consultation, on a board's decision that pre-empts the outcome of that consultation. We will have the opportunity to ask for legal advice on that. As regards the bigger picture, we welcome the voice of young people in the whole process.

86. Mr McNarry: How far do you take the pursuit of legal advice? I do not want to put words into anyone's mouth; I know that I am treading on issues on which legal advice has been sought and is probably still awaited. Would you support a school in a legal challenge on behalf of the children?

87. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: It would depend on the nature of the legal challenge and whether there was no other route to be taken. In that case, we would support a challenge. We would have to make sure that there was no other available process.

88. Mr McNarry: That is a politician's answer.

89. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: It is a commissioner's answer. I have to make sure that there is no other process that those people can go through. It is in my legislation. I cannot step on someone else's toes. However, if, for instance, parents decided to take legal action, we could support them financially to help them to take the case if they could not draw down legal aid.

90. Mr McNarry: That is what I wanted to hear. Thank you.

91. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: That would depend on my budget and the cost of the case.

92. Mr McNarry: Now you are behaving more like a politician. You sound like John O'Dowd, talking about budgets.

93. Mr McDevitt: You have been reviewing the Executive's performance against the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. How do you assess things generally at the moment?

94. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: The commitment to children and young people has been rolled back hugely. In the first Assembly, there was the children's fund as well as this office and the children and young people's unit being set up. When the Assembly was suspended, we had the children and young people's package, which is now gone. The children and young people's unit has also gone. We believe that the Executive have an opportunity in the life of this Assembly to make a real difference. We hope that they will make children and young people in particular a priority in the Programme for Government. The piece of work that we launched last week helped to give us some of the evidence that we needed behind that.

95. Mr McDevitt: What is your view of the Executive's capacity to fulfil their article 12 duties? Do you think that they are fulfilling those duties to children to give them full participation in decision-making?

96. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Some work has been started, but there is a lot more to be done. We have asked each and every Department to sign up to a participation statement of intent, and all but one have done that. Our job now is to go back and ask exactly how they are doing that. The Executive will have the opportunity to find out how they are living up to their article 12 obligations by having people such as the children's champions being answerable to the ministerial subcommittee, when and if it meets.

97. Mr McDevitt: That is another matter. On the specific matter of school councils, I take it that what you are saying today is that guidance would be great, and there is no reason why we could not see it, but that you would still like to see those in a statutory body.

98. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Yes.

99. Mr McDevitt: I agree with the Chairperson that there is so much that we can build on and, potentially, be even braver about. If we were to put school councils on a statutory footing — picking up on the Chairperson's point about giving students a direct role in the governance of a school by giving them a seat on the board of governors — do you believe that student councils should have the right to nominate to the board of governors?

100. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Yes. It would be a democratic process through which they would elect their chair or a member of their school council to represent them on that, and it is important that the young people would have the opportunity to do that.

101. Dr Montgomery: I will clarify the previous point. Wales has associate governors, and up to two pupils from the school council can be elected to serve on that. That is in legislation in Wales.

102. Mr McDevitt: What level of decision-making do you think should be devolved to a student council? How meaningful should its role be in decision-making?

103. Dr Montgomery: As the commissioner said, every school will determine what its school council should be about. We are very much of the mind that every school is unique and has its particular needs. A primary school, for example, will approach a school council quite differently from a post-primary school and from a special school. It is about focusing on that school's needs and on the relationship between teachers and pupils and how they wish to develop that. It is a fine balance between teachers' input, senior managers' input and managing a school council so that it works effectively and does not have too much control. That is a fine balance that needs to be worked at in schools.

104. Mrs Kinghan: That is what we found. As Patricia said, there was a huge variance in the involvement of pupils and, in some cases, the involvement of teachers. In some schools, there was a clear involvement and an idea of the benefits that that could bring. That is where guidance would be useful in that there would be standards to which people could aspire. Perhaps not everyone would get there in the first year or the first five years, but at least they would have something to aspire to. We want a policy layer to ensure that that is taken forward.

105. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: Whatever young people's level of involvement, it is important that, if they ask for something that is impossible to give, as long as the opportunity exists to explain why that is the situation, at least they will feel that their voice has been heard.

106. The Chairperson: Following on from David's point, Patricia, is there an obligation on education and library boards (ELBs) to consult with school councils or school pupils on development proposals, of whatever nature, including closures or changes to a school?

107. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: There is no specific remit, but, under article 12 of the UNCRC, there should be a remit for young people to have a voice in those types of decisions.

108. Mrs Kinghan: The Education (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 refers to bullying policies, but that does not go across all policies. That is where there is a discrepancy in children's voices being heard. A UN committee has said that, when a decision affects a child, that child should be asked, if he or she has the capacity.

109. The Chairperson: That is a very interesting point.

110. Patricia, perhaps at some stage you can convey to us examples of good practice in school councils. We were very impressed by those in Limavady and Harberton Special School. You mentioned some in Wales and some in the Republic. Perhaps you can give us some good examples, and the Committee will be interested in seeing them.

111. Mrs Lewsley-Mooney: I certainly will.

112. The Chairperson: Thank you. I have no doubt that we will come back to you. You are more than welcome to stay and hear the Department's presentation.

16 November 2011

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mr Mervyn Storey (Chairperson)

Mr David McNarry (Deputy Chairperson)

Ms Michaela Boyle

Mr Conall McDevitt

Miss Michelle McIlveen

Witnesses:

|

Ms Eve Stewart |

Department of Education |

113. The Chairperson: Linda and Eve, you are very welcome. I am sorry for the delay and for holding you back. We have had a presentation from the Children's Commissioner, and we want to raise a number of issues with you. If you have some comments to make, please proceed. We received your briefing paper.

114. Ms Linda Wilson (Department of Education): The effective participation of young people — that is, the opportunity to influence processes and decisions about their lives and to bring about change — is an important consideration in the Department of Education's (DE) approach to education.

115. As part of the Department's school improvement policy, Every School a Good School, DE wants a greater focus on engagement in schools, particularly with pupils. The involvement of young people is now identified as an indicator of effective performance, and it is also a specific goal in promoting engagement among schools and pupils, parents, families and communities.

116. As part of the school development planning process, schools are required to demonstrate that there is a commitment to involve young people in discussions and decisions in school life that directly affect them and to listen to their views. A schedule to the regulations identifies arrangements to consult and take account of pupils, parents, staff and others in the preparation of the plan.

117. Together Towards Improvement sets out the inspection framework; the Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI) introduced that process to enable schools to self-evaluate. One indicator of quality leadership and management is the encouragement of learners' involvement in discussions, decisions and aspects of school life that affect them directly, thus ensuring that the student voice is represented. That is underpinned by other parts of the process, which, for example, include shared evaluation of teaching and learning and stakeholder involvement. Paragraph 5 of our briefing paper sets out examples of effective pupil engagement in addition to school councils. It highlights a number of ways in which pupils might be involved. It includes strategic examples, such as involvement in the governance and management of schools, input in classroom teaching through assessment and class-led form work, and the use of various methods to canvass pupils' views.

118. During a school inspection, the Education and Training Inspectorate will seek to identify good practice and examples of positive pupil engagement. The Every School a Good School policy refers to the provision of a resource to support school councils specifically and to encourage all schools to set up councils or other fora to ensure that pupils have a voice in decisions on the running of their school. In that respect, DE has referenced the Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People's (NICCY) Democra-School guidance on its website.

119. An effective school council can make an important contribution to pupils' educational development. However, there are other ways to engage effectively with pupils. School councils are one of a number of means for schools to engage with pupils. Although DE supports the concept of school councils in principle, the key aim is to encourage all schools to find meaningful ways to give pupils a voice that can be heard. In that context, the Department would not seek to be prescriptive, but rather encourage, facilitate and promote means of effective and meaningful pupil engagement.

120. The Chairperson: Thank you for your presentation and briefing paper. Will you clarify something for us? The Children's Commissioner has just informed us that, after discussions with the Department over the past number of years, DE was in the process of introducing guidelines on school councils but has now decided not to do so until the outcome of our inquiry is published. Do you agree that it would be helpful if the Department were to share its current thinking on those guidelines, so that, as we continue with our inquiry, we will end up with something that is meaningful, useful and has buy-in from everybody about how we proceed on the issue?

121. In your presentation, you refer to a requirement for schools to evaluate participation, the exchange between pupils, and so on. However, paragraph 4 of your briefing paper states:

"The Education and Training Inspectorate does not evaluate individual aspects of pupil engagement such as school councils".

122. There seems to be a disparity. On the one hand, departmental documents provide encouragement to schools. On the other hand, the inspectorate decides not even to evaluate the merit, value or worth of that process. Do you think that that needs to be changed?

123. Ms L Wilson: As I understand it, the inspectorate does not specifically evaluate whether a school has a school council. It looks at whether there is meaningful pupil engagement. The inspectorate would say that, as it goes about its work, it talks to pupils, observes how schools operate, how classrooms are run, how pupils behave in and contribute to class, and so on. It would take the view that, although it does not evaluate it specifically, it looks for it, comments on it and sees whether it is part of the school process.

124. Mr McNarry: Chairman, I am not too sure that you got an answer to your question.

125. How long have you been working on the issue?

126. Ms L Wilson: I came to DE in September 2009.

127. Mr McNarry: Is it true — I ask only because I understand that it might be — that a draft document has been in circulation in the Department since February?

128. Ms L Wilson: We have a very rough working document, which we pulled together following discussions with NICCY. The document needs further work, and it needs to be set in a wider context. We had helpful engagements with NICCY, which provided some useful steers. I then discussed the matter with departmental colleagues, who put other points of view to me, such as whether the issue was school councils or ensuring effective pupil participation by a variety of means. If a school council is working well, it can be highly valuable. However, the Department does not want a school council to be tokenistic, with the focus being on process rather than outcomes. It was clear from speaking to colleagues that there are issues around setting the matter in a wider context.

129. Mr McNarry: Since September two years ago, you produced, in February, a rough draft. Could the Committee see that rough draft?

130. Ms L Wilson: Yes, certainly.

131. Mr McNarry: We would be obliged if you would pass that down to us. I appreciate and follow your line of thinking. Now that we know that you have a rough draft that is likely to be on guidance, is it true that you are holding back on its publication and are waiting for the outcome of the Committee's inquiry?

132. Ms L Wilson: The Minister is embarking on a major programme of work and reform. He will decide the priorities and the work that the Department has to take forward and make decisions about that.

133. Mr McNarry: Are you telling us that the Minister does not see that as a priority?