Report on Safeguarding Northern Ireland's Listed Buildings

Session: 2011/2012

Date: 04 July 2012

Reference: Report on Safeguarding Northern Ireland's Listed Buildings

ISBN: 978-0-339-60439-1

Mandate Number: Tenth Report

nia-64-11-15.pdf (1.52 mb)

Public Accounts Committee

Report on Safeguarding

Northern Ireland's Listed Buildings

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the Committee

Relating to the Report and the Minutes of Evidence

Ordered by The Public Accounts Committee to be printed 4 July 2012

Report: NIA 64/11-15 Public Accounts Committee

Mandate 2011/15 Tenth Report

***Corrigendum***

On page 6, in paragraph 17 after "DOE policy since 2008 is that", delete "all" and insert "most".

Certain categories of listed buildings (such as lower grade churches, those owned by Government/public bodies, housing associations funded by public monies, and large commercial organisations and multinationals) are not eligible for assistance.

Membership and Powers

The Public Accounts Committee is a Standing Committee established in accordance with Standing Orders under Section 60(3) of the Northern Ireland Act 1998. It is the statutory function of the Public Accounts Committee to consider the accounts, and reports on accounts laid before the Assembly.

The Public Accounts Committee is appointed under Assembly Standing Order No. 56 of the Standing Orders for the Northern Ireland Assembly. It has the power to send for persons, papers and records and to report from time to time. Neither the Chairperson nor Deputy Chairperson of the Committee shall be a member of the same political party as the Minister of Finance and Personnel or of any junior minister appointed to the Department of Finance and Personnel.

The Committee has 11 members including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and a quorum of 5.

The membership of the Committee since 23 May 2011 has been as follows:

Ms Michaela Boyle (Chairperson)[1]

Mr Joe Byrne (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Mr Michael Copeland

Mr John Dallat

Mr Alex Easton

Mr Paul Girvan

Mr Ross Hussey

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Mr Adrian McQuillan[2]

Mr Conor Murphy[3]

[1] With effect from 2 July 2012 Ms Michaela Boyle replaced Mr Paul Maskey

[2] With effect from 24 October 2011 Mr Adrian McQuillan replaced Mr Paul Frew

[3] With effect from 23 January 2012 Mr Conor Murphy replaced Ms Jennifer McCann

Table of Contents

List of abbreviations used in the Report

Report

Surveying Historic Buildings to Assess their Suitability for Listing

Measuring the Performance of NIEA's Grant Scheme in Improving the Listed Buildings Stock

Enforcing Measures to Safeguard Listed Buildings from Damage or Destruction

Appendix 1

Appendix 2:

Appendix 3:

Appendix 4:

List of Abbreviations used in the Report

the Committee - Public Accounts Committee

DOE - Department of the Environment

NIEA - Northern Ireland Environment Agency

OFMDFM - Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister

Executive Summary

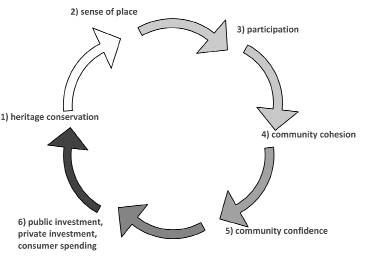

1. Listed buildings are an important part of the built heritage. They can help to maintain local identity and contribute to quality of life for communities, as well as playing an important role in tourism and economic development initiatives. There are currently around 8,500 listed buildings in Northern Ireland. The decision to list a building is based on a survey undertaken by the Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA) that assesses each building against specific criteria, including condition and style.

2. The survey to identify buildings suitable for listing was originally due for completion in 2008 but is not now expected to be finished until 2020, taking in total 25 years. The original timeframe for the work was unrealistic, and management of the work was not as effective as it should have been. Slow progress of this nature increases the risk that buildings that should be listed could be demolished or damaged before they are surveyed. It is therefore important that there is no further slippage in the timetable.

3. Almost 60 per cent of buildings surveyed up to March 2012 did not meet the standard for listing. This element of the survey cost £1.57 million. Unnecessary survey work is a poor use of taxpayers' money, and NIEA must do more to reduce the numbers of unsuitable buildings that are being surveyed.

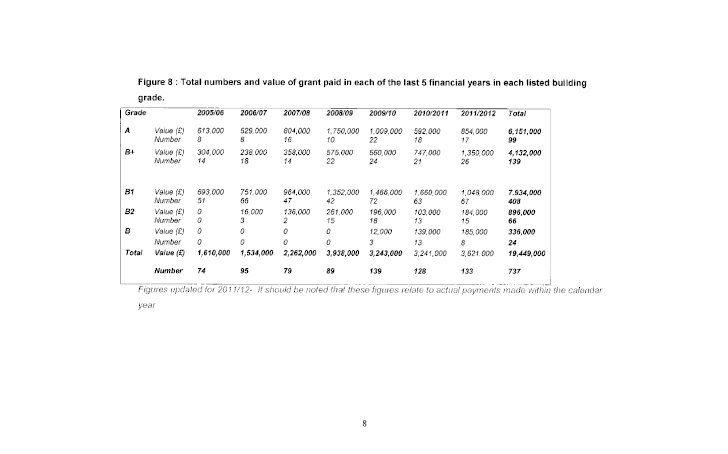

4. There is no statutory requirement for owners of listed buildings to maintain them in good condition, and NIEA offers grant assistance in order to encourage conservation. Despite having provided almost £20 million of grants since 2005-06, the only specific measure of performance for the historic buildings grant scheme since it began in 1974 has been the degree to which the grants budget for each financial year has been spent. This is unacceptable. In the absence of appropriate performance measures, the Department cannot provide evidence on the effectiveness of the scheme as a whole.

5. The NI Sustainable Development Strategy contains a target to remove 200 structures from the Built Heritage at Risk Register by 2016. The Committee considered that this target could be met, in theory, if buildings were simply lost: that is, if they went from being 'at risk' to 'beyond rescue'. This is a particular risk where a listed building occupies a site that would be more valuable to its owners if the building were removed. Currently, there is no mechanism that allows NIEA to target its grant aid on the most important or urgent cases on the Built Heritage At Risk register, and this needs to be addressed.

6. Around 850 listed buildings are owned by the public sector, which has specific responsibilities to maintain them in a good condition. Despite this, 31 are currently on the at-risk register. Furthermore Departments, including DOE itself, have not complied with requirements to report on the condition of their listed buildings. A new protocol setting out requirements for the care of the government historic estate was launched on 19 June 2012. This is important, as the public sector must act as an exemplar and be seen to give a clear lead in this area.

7. NIEA recognises the need to be more willing to take enforcement action in cases where persuasion and negotiation have clearly failed. The need for timely enforcement action is illustrated by the Stable Block at Sion Mills, where NIEA's failure to act decisively resulted in deterioration to a point that threatened its long-term survival. It is completely unacceptable that NIEA dragged its heels on this case for so many years, and lessons must be learnt from it.

8. Some listed buildings originally owned by public bodies have not fared well since they were acquired by private owners. They are particularly vulnerable when they were already in poor condition at the time of sale, as was the case with the former courthouse on Crumlin Road in Belfast. NIEA should have taken decisive action long before now to halt its decline, and its failure thus far to use its powers to rescue the courthouse makes it appear toothless and ineffective.

Summary of Recommendations

Recommendation 1

1. The Committee recommends that NIEA puts in place a formal plan to ensure that the listed buildings survey is completed as soon as practicable and by 2020 at the latest. The plan should specify the remaining work to be done; the associated budgetary and personnel requirements; and delivery milestones against which to measure performance on an ongoing basis.

Recommendation 2

2. Undertaking unnecessary survey work is a poor use of taxpayers' money. At a time when public expenditure is particularly constrained, NIEA must be able to demonstrate that it is making best use of its resources. The Committee recommends that NIEA reduces the proportion of surveyed buildings that do not qualify for listing and sets an early date for achieving its 40 per cent target rate.

Recommendation 3

3. It is essential that grant schemes have clear objectives and that the outcomes of the expenditure can be properly evaluated. The Committee recommends that NIEA puts in place a formal performance measurement framework for the listed buildings grant scheme that will allow the results achieved from this element of its expenditure to be quantified and used to revise the scheme, as necessary.

Recommendation 4

12. It is important that grant is targeted on the most vulnerable and valuable buildings. The Committee recommends that NIEA formally prioritises the structures on the Built Heritage at Risk Register and actively encourages owners to access available grant aid in order to undertake the improvements necessary to remove them from the register.

Recommendation 5

4. The new protocol for the care of public listed buildings is an important step in safeguarding them. The Committee recommends that the NIEA publishes the finished condition reports for listed buildings owned by the DOE on its website, to act as a benchmark for assessing the performance of the rest of the public sector. It should also publish the reports for other publicly owned listings when they become available.

Recommendation 6

5. Timely and robust use of enforcement powers, including vesting, is vital to safeguard listed buildings and rescue those that are at risk, in order to send a strong message to negligent owners who fail to prevent deterioration or damage. The Committee recommends that NIEA steps up its enforcement effort, using trigger points to instigate specific measures in individual cases where persuasion and negotiation have clearly failed.

Recommendation 7

6. The public sector cannot shirk its responsibilities for its former listed buildings that are now in private ownership. The Committee recommends that the Department takes timely and effective enforcement action to secure the future of any such buildings and, if required, to rescue those that are at risk. Such action should include carrying out repairs directly and recouping the cost from the owners or, if necessary, being prepared to take the buildings back into public ownership.

Introduction

1. The Public Accounts Committee (the Committee) met on 23 May 2012 to consider the Comptroller and Auditor General's report "Safeguarding Northern Ireland's Listed Buildings". The main witnesses were:

- Mr Leo O'Reilly, Accounting Officer of the Department of the Environment;

- Mr Michael Coulter, Director of Built Heritage, NI Environment Agency;

- Mr Manus Deery, Principal Conservation Architect, Historic Buildings Unit, NI Environment Agency;

- Ms Fiona McCandless, Director, Department of the Environment Local Planning Division;

- Mr Kieran Donnelly, Comptroller and Auditor General; and

- Mr John McKibbin, Acting Treasury Officer of Accounts.

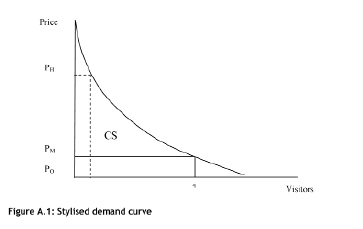

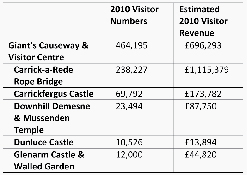

2. Listed buildings are an important part of the built heritage, which is an irreplaceable cultural asset. They can help to maintain local identity and contribute to quality of life for communities, as well as playing an important role in tourism and economic development initiatives. A recent report[1] commissioned by the Department of the Environment estimated that the historic environment as a whole contributes £250 million of tourism revenue each year, £135 million of which comes from non-domestic visitors.

3. The Department for the Environment is responsible for undertaking measures to safeguard the built heritage and its conservation role is carried out by the Northern Ireland Environment Agency.

4. In taking evidence, the Committee focused on:

- progress of the survey to identify buildings suitable for listing;

- the performance of the historic grant scheme in improving listed buildings; and

- enforcement of measures to safeguard buildings from damage or destruction.

Surveying historic buildings to assess their suitability for listing

5. There are currently around 8,500 listed buildings in Northern Ireland. Listing is a statutory designation that affords a historic building protection against unauthorised alteration or demolition. The decision to list a building is based on a survey that assesses each building against specific criteria, including condition and style. In 1995, the NI Environment Agency (NIEA) began a comprehensive survey exercise to update and improve the quality of information in its listed buildings database. No budget was ever set for the survey overall, but costs up to 31 March 2012 were approximately £2.6 million.

Delays in completing the survey

6. The survey was originally due for completion in 2008 but is not now expected to be finished until 2020, taking a total of 25 years. The Department acknowledged to the Committee that the survey has gone on for longer than it should. The original timeframe for the work was unrealistic, and the stop-start rate of progress in the first 10 years indicates that management of the work was not as effective as it should have been. NIEA underestimated the amount of work involved with the survey, did not provide enough staff resources to process the results of the survey and failed to manage the contractors effectively.

7. There was also poor cost control. NIEA did not set a budget for the work; survey contractors were paid on hourly rate rather than a fixed cost; and there were significant variations in the cost of the contracts per building surveyed. This issue has been rectified in the current contracts, where NIEA determines the workload in advance and the contracts are fixed-price.

8. Resource constraints in 2011-12 have once again led to a delay in processing survey records in NIEA. Slow progress of this nature increases the risk that historic buildings could be demolished or damaged before they are surveyed. To address this risk, there are arrangements in place for ad hoc surveys of individual structures where NIEA becomes aware of a particular threat to their survival. Nevertheless, it is important that there is no further slippage in the timetable for completing the survey.

Recommendation 1

9. The Committee recommends that NIEA puts in place a formal plan to ensure that the listed buildings survey is completed as soon as practicable and by 2020 at the latest. The plan should specify the remaining work to be done; the associated budgetary and personnel requirements; and delivery milestones against which to measure performance on an ongoing basis.

The scope of survey work

10. Almost 60 per cent of buildings surveyed up to March 2012 did not meet the standard for listing. This element of the survey cost £1.57 million. While it is to be expected that some buildings will be rejected, this rate is clearly too high, and NIEA took too long to get to grips with the situation. The Department said that the failure rate is currently around 50 per cent, but that it is working to reduce it gradually to 40 per cent. The Committee welcomes the improved scoping arrangements now used by NIEA to target buildings for survey before contractors begin work. This is a key step towards achieving the 40 per cent target.

11. In order to reduce this failure rate further, it is important that NIEA uses all relevant sources of information. Before commencing survey work in any given area, NIEA engages widely with stakeholders, including local Councils, other public bodies and voluntary groups, in order to gather relevant information. The Committee would also expect NIEA to explore additional sources of information, including electronic mapping information from OSNI. NIEA must minimise the likelihood that large numbers of unsuitable buildings could be included in the survey, to ensure that it uses public monies efficiently and effectively.

Recommendation 2

12. Undertaking unnecessary survey work is a poor use of taxpayers' money. At a time when public expenditure is particularly constrained, NIEA must be able to demonstrate that it is making best use of its resources. The Committee recommends that NIEA reduces the proportion of surveyed buildings that do not qualify for listing and sets an early date for achieving its 40 per cent target rate.

Measuring the performance of NIEA's grant scheme in improving the listed buildings stock

13. There is no statutory requirement for owners of listed buildings to maintain them in good condition, and NIEA offers grant assistance in order to encourage conservation. The rate of grant reflects the higher cost of making repairs to listed buildings relative to more modern buildings.

Assessing the impact of grant assistance

14. Since 2005-06, around 9 per cent of listed buildings have received grant aid of almost £20 million towards the cost of approved repairs. However, despite this significant expenditure, NIEA's only specific measure of performance for the historic buildings grant scheme since it began in 1974 has been the degree to which the budget for each financial year has been spent.

15. The grant scheme is a key element of NIEA's conservation work and a driver for delivering positive change. It is therefore important that NIEA is able to measure the scheme's success in persuading and enabling owners to undertake repairs, not least in cases where no other source of grant funding is available to them. In the Committee's view, the Department cannot provide evidence of the overall effectiveness of the scheme in the absence of such basic performance measures.

Recommendation 3

16. It is essential that grant schemes have clear objectives and that the outcomes of the expenditure can be properly evaluated. The Committee recommends that NIEA puts in place a formal performance measurement framework for the listed buildings grant scheme that will allow the results achieved from this element of its expenditure to be quantified and used to revise the scheme, as necessary.

Targeting expenditure on buildings that are at risk

17. DOE policy since 2008 is that all listed buildings in certain categories are equally eligible for grant aid, regardless of their importance, rarity or vulnerability. The Department recognises, however, that funding constraints mean that some targeting may be necessary, in the future.

18. The NI Sustainable Development Strategy contains a target to remove 200 structures from the Built Heritage at Risk Register[2] by 2016. NIEA did not meet its annual target for the number to be removed from the Register in 2011-12 but told the Committee it expects to achieve the overall 2016 target. While this is welcome, the Committee considered that this target could be met, in theory, if buildings were simply lost: that is, if they went from being 'at risk' to 'beyond rescue'. This is a particular risk where a listed building occupies a site that would be more commercially valuable to its owners if the building were removed.

19. Previously, NIEA's efforts in respect of buildings at risk focused largely on encouraging their owners to repair them. While this is the most desirable outcome, the Committee welcomes NIEA's recent moves to prioritise buildings on the Register for more targeted action, including enforcement measures, where persuasion tactics have failed. This move to a firmer approach in specific problem cases is overdue. However the Committee believes there is scope to go further and put in place a mechanism to direct grant aid to the most important or urgent cases.

Recommendation 4

20. It is important that grant is targeted on the most vulnerable and valuable buildings. The Committee recommends that NIEA formally prioritises the structures on the Built Heritage at Risk Register and actively encourages owners to access available grant aid in order to undertake the improvements necessary to remove them from the register.

Conserving listed buildings owned by the public sector

21. Around 10 per cent of listed buildings are owned by the public sector, which has specific responsibilities to maintain them in a good condition. Despite this, 31 of the 858 listed buildings owned by public bodies are currently on the at-risk register, and some have fallen into serious disrepair as a result of long-term neglect. This is unacceptable. The public sector must act as an exemplar and be seen to give a clear lead in this area.

22. In addition, Government departments, including DOE itself, have not complied with formal requirements to report on the condition of their listed buildings. The condition reports were intended to include a planned programme of maintenance and repairs and a protection strategy (repair, re-use or disposal) for buildings at risk.

23. A new Northern Ireland protocol setting out requirements for the care of the government historic estate has been agreed between NIEA and OFMDFM and was launched on 19 June 2012. By June 2013, bodies will be required to submit condition reports to NIEA, who will report overall results to the Assembly's Environment Committee. The Department intends to use the reports on its own listed buildings to illustrate to other Departments what is required by the protocol. This is important, and the Committee is strongly of the view that DOE must be able to demonstrate that it is leading by example and fully discharging its own responsibilities.

Recommendation 5

24. The new protocol for the care of public listed buildings is an important step in safeguarding them. The Committee recommends that NIEA publishes the finished condition reports for the listed buildings owned by DOE on its website, to act as a benchmark for assessing the performance of the rest of the public sector. NIEA should also publish the condition reports for other publicly owned listed buildings when they become available.

Enforcing measures to safeguard listed buildings from damage or destruction

25. DOE Planning is responsible for issuing legal permissions to alter listed buildings and for enforcing regulations to protect them, up to and including prosecution. NIEA is responsible for enforcement action in cases where owners have allowed their listed structures to fall into serious disrepair. This includes issuing statutory notices[3] requiring specific action to address identified problems within a set time frame.

Effective use of enforcement powers

26. Achieving the best enforcement outcome requires close collaboration between Planning and NIEA, underpinned by comprehensive and shared management information. After several years' delay, formal joint working procedures and a single heritage crime database for use by both bodies are now in place. The Department is also working towards implementing a 2007 Criminal Justice Inspectorate recommendation for a single enforcement database covering all of its enforcement activities.

27. Now that there is better information to act as a basis for legal proceedings, NIEA recognises that it must be more willing to take enforcement action in cases where persuasion and negotiation have clearly failed. The need for timely action is illustrated by the case of the Stable Block at Sion Mills, where NIEA's failure to act decisively resulted in deterioration to a point that threatened its long-term survival. After several years of negotiation and threatened legal action, DOE eventually vested the property in 2008, but only after part of it had collapsed.

28. The Committee considers it completely unacceptable that NIEA dragged its heels on this case for so many years, when it was clear that the owner was not going to undertake the necessary repairs. NIEA said that lessons have been learned from this case and, in the past year, it has issued an increased number of Urgent Works Notices and warning letters, with positive results.

Recommendation 6

29. Timely and robust use of enforcement powers, including vesting, is vital to safeguard listed buildings and rescue those that are at risk in order to send a strong message to negligent owners who fail to prevent deterioration or damage. The Committee recommends that NIEA steps up its enforcement effort, using trigger points to instigate specific measures in individual cases where persuasion and negotiation have clearly failed.

Former public buildings that are now at risk

30. Some listed buildings originally owned by public bodies have not fared well since they were acquired by private owners. They are particularly vulnerable when they were already in poor condition when in public ownership, as was the case with the former courthouse on Crumlin Road in Belfast. This unique landmark building was already in need of repair when it was sold by Courts Service and it has suffered serious decay and fire damage in the years since then.

31. The courthouse is a building of considerable historical significance and the neglect it suffered in public ownership was disgraceful. However, given the continued and rapid deterioration that has occurred following transfer to the private sector, it is simply unacceptable that NIEA did not take decisive action long before now to halt the decline. In the Committee's view, NIEA's failure thus far to use the full range of its powers to rescue the courthouse makes it appear toothless and ineffective. This must never be allowed to happen again.

Recommendation 7

32. The public sector cannot shirk its responsibilities for its former listed buildings that are now in private ownership. The Committee recommends that the Department takes timely and effective enforcement action to secure the future of any such buildings and, if required, to rescue those that are at risk. Such action should include carrying out repairs directly and recouping the cost from the owners or, if necessary, being prepared to take the buildings back into public ownership.

[1] "Study of the Economic Value of Northern Ireland's Historic Environment", launched by the Minister of the Environment 21 June 2012.

[2] This is an online database that provides information on each structure, by County. BHARNI is maintained on NIEA's behalf by the Ulster Architectural Heritage Society

[3] Urgent Works Notices require owners to undertake emergency repairs (for example, to keep the building weatherproof and safe from collapse). Repairs Notices specify the repair work needed to preserve the building. If this is not done within the required time frame, the Department may make a compulsory purchase to safeguard it.

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

of the Committee

Relating to the Report

Wednesday, 9 May 2012

The Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Maskey MP (Chairperson)

Mr Michael Copeland

Mr Alex Easton

Mr Paul Girvan

Mr Ross Hussey

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Mr Adrian McQuillan

Mr Conor Murphy MP

In Attendance: Miss Aoibhinn Treanor (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Phil Pateman (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Gavin Ervine (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Darren Weir (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Joe Byrne (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Mr John Dallat

2:00 pm The meeting opened in public session.

4. Briefing on the NIAO Report on 'Safeguarding Northern Ireland's Listed Buildings'

Mr Kieran Donnelly, Comptroller and Auditor General; Mr Eddie Bradley, Assistant Auditor General; and Ms Ursula Moyna, Audit Manager; briefed the Committee on the report.

2:17 pm The meeting went into closed session after the C&AG's initial remarks.

2:43 pm Mr Girvan entered the meeting.

2:45 pm Mr McLaughlin entered the meeting.

The witnesses answered a number of questions put by members.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 23 May 2012

The Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Maskey MP (Chairperson)

Mr Joe Byrne (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Mr Michael Copeland

Mr Alex Easton

Mr Paul Girvan

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Mr Adrian McQuillan

In Attendance: Miss Aoibhinn Treanor (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Phil Pateman (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mr Gavin Ervine (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Darren Weir (Clerical Officer)

Ms Angela Kelly (Assembly Legal Services)

Apologies: Mr John Dallat

Mr Ross Hussey

Mr Conor Murphy MP

2:00 pm The meeting commenced in closed session.

4. Evidence on the Northern Ireland Audit Office Report 'Safeguarding Northern Ireland's Listed Buildings'.

The Committee took oral evidence on the above report from:

- Mr Leo O'Reilly, Accounting Officer, Department of the Environment (DOE);

- Mr Michael Coulter, Director of Built Heritage, Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA);

- Mr Manus Deery, Principal Conservation Architect, Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA); and

- Ms Fiona McCandless, Director Local Government Planning Division, Department of the Environment (DOE).

3:11 pm Mr Anderson left the meeting.

3:18 pm Mr Anderson entered the meeting.

3:21 pm Mr Copeland left the meeting.

3:24 pm Mr Byrne left the meeting.

3:28 pm Mr Byrne and Mr Copeland entered the meeting.

3:36 pm Mr McQuillan left the meeting.

3:41 pm Mr Copeland left the meeting.

3:42 pm Mr McQuillan entered the meeting.

3:53 pm Mr Girvan left the meeting.

3:54 pm Mr McLaughlin left the meeting.

3:59 pm Mr Copeland and Mr Girvan entered the meeting.

4:02 pm Mr Girvan left the meeting.

4:10 pm Mr Girvan entered the meeting.

4:13 pm Mr Easton left the meeting.

4:33 pm Mr McQuillan left the meeting.

The witnesses answered a number of questions put by the Committee.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to request further information from the witnesses.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 30 May 2012

Room 29, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Paul Maskey MP (Chairperson)

Mr Joe Byrne (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Michael Copeland

Mr John Dallat

Mr Alex Easton

Mr Paul Girvan

Mr Ross Hussey

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Mr Adrian McQuillan

Mr Conor Murphy MP

In Attendance: Miss Aoibhinn Treanor (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Phil Pateman (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Danielle Saunders (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Darren Weir (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Sydney Anderson

1:36 pm The meeting commenced in closed session.

5. Issues Arising from the Oral Evidence Session on 'Safeguarding Northern Ireland's Listed Buildings'

The Committee considered an issues paper relating to the previous week's evidence session.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to proceed with the drafting of the report on the basis of its discussion and the issues paper.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 4 July 2012

Room 29, Parliament Buildings

Present: Ms Michaela Boyle (Chairperson)

Mr Joe Byrne (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Mr Michael Copeland

Mr John Dallat

Mr Alex Easton

Mr Paul Girvan

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Mr Adrian McQuillan

In Attendance: Miss Aoibhinn Treanor (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Phil Pateman (Assistant Assembly Clerk)

Mrs Danielle Saunders (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Darren Weir (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Ross Hussey

2:02 pm The meeting opened in public session.

6. Consideration of Draft Committee Report on 'Safeguarding Northern Ireland's Listed Buildings'

The Committee considered its draft report on 'Safeguarding Northern Ireland's Listed Buildings'.

3:50 pm Mr McQuillan left the meeting.

Paragraphs 1 - 5 read and agreed.

Paragraph 6 read, amended and agreed.

3:55 pm Mr Copeland left the meeting.

Paragraphs 7 - 8 read and agreed.

Paragraph 9 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraphs 10 -22 read and agreed.

Paragraphs 23 – 24 read, amended and agreed.

Paragraph 25 read and agreed.

Sub header read, amended and agreed.

Paragraph 26 read and agreed.

Paragraphs 27 - 31 read and agreed.

4:12 pm Mr Byrne left the meeting.

Paragraph 32 read, amended and agreed.

Consideration of the Executive Summary

Paragraph 1 – 8 read and agreed.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the correspondence to be included within the report.

Agreed: The Committee ordered the report to be printed.

[EXTRACT]

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

23 May 2012

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Mr Paul Maskey (Chairperson)

Mr Joe Byrne (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Sydney Anderson

Mr Michael Copeland

Mr Alex Easton

Mr Paul Girvan

Mr Mitchel McLaughlin

Mr Adrian McQuillan

Witnesses:

|

Ms Fiona McCandless |

Department of the Environment |

|

|

Mr Michael Coulter |

Northern Ireland Environment Agency |

1. The Chairperson: We are joined by Mr Leo O'Reilly, accounting officer for the Department of the Environment (DOE). He is here to respond to the Committee. Mr O'Reilly, you and your team are very welcome. I will hand over to you to introduce them.

2. Mr Leo O'Reilly (Department of the Environment): Thank you, Chairman. On my left is Manus Deery, principal conservation architect with the historic buildings unit in the Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA). To my right is Michael Coulter, director of built heritage in the NIEA, and to his right is Fiona McCandless, director of local planning division in the Department of the Environment.

3. The Chairperson: As I say, you are all very welcome. I think that you have been here before anyway, but the usual procedure is that I will start by asking a few questions to set the scene before other members come in. So, nothing has changed.

4. Let me first of all apologise for keeping you waiting for a bit longer today. This session was supposed to start at 2.00 pm but we had to get through other items first. So apologies for that. Hopefully, we do not keep you longer than we need to.

5. Paragraph 2.4 talks about the slow progress of the second survey. It tells us about the review undertaken by the agency itself and says that it might end up taking 30 years to complete, compared with the original target of 11 years. I am no mathematician, but I know that that is a 19-year difference, which is a terribly long time. Can you justify why the timing of the survey has gone so far off the rails? For it to be 19 years out of sync is just horrendous.

6. Mr O'Reilly: Thank you. Obviously, the survey has gone on for a very long time, and that has been a focus of concern. I suppose the basic answer to your question is that it has gone on longer than it should have. The report identifies the factors that explain some of the reasons why it has lasted for quite a long time, and they fall under three broad areas.

7. The first factor that affected the length of the survey was an underestimation at the beginning of just how much work would be involved, particularly in relation to the decision on the survey's coverage and scope in respect of the range of buildings to be surveyed and re-surveyed during the second survey exercise.

8. The second factor that impacted on the length of time that the exercise has taken to date is the various stages of contractual relationships that have been entered into. As the report highlights, the nature of the contractual relationships has changed over time. I suppose, to some extent, the agency was going through a learning process in seeking to find the optimum contractual model that would provide the type and quality of work that it required the survey to undertake at a reasonable cost to the public purse.

9. The third key factor that has impacted on the length of time is resource availability. In a sense, that is at two levels. Financial constraints impacted from time to time on the pace of the survey, particularly in the period from 1999 to 2001, when there were some significant reductions in the budget available to carry out the survey.

10. A second key aspect of the resource issue was the availability of staff in the agency to process the survey outcomes once the basic survey work had been carried out by fieldwork staff who were primarily contractors. The varying availability of those staff in the agency over the years impacted on the pace at which the information coming into the agency could be processed, which, in turn, impacted on the length of time it took to make decisions about listing a particular building and on the necessary consultation work carried out to reach a final decision before a formal listing took place.

11. Those factors — coverage and the nature of the survey, contractual relationships, the resources available over time and the deployment of those resources — can explain why the survey has lasted for so long. However, as I said at the beginning, it has lasted longer than, I think, any of us wished to see it last.

12. The Chairperson: I think so. It is estimated to last 30 years, which is 19 years more than expected. You gave three reasons, one of which was contractual. Is that because individuals were paid an hourly rate instead of a fixed cost? Is that why it is taking so long?

13. Mr O'Reilly: As the report records, when the second survey began in 1997, four contracts were let, covering four separate geographical areas of Northern Ireland. Those were let on an hourly basis, not on a fixed-price basis. As the report also records, the reason for taking that basic approach at the time was that there was uncertainty about the nature and the extent of the work that would have to be carried out by the contractors. However, as the report shows, after a couple of years, the analysis showed that there were significant variations in the cost of those contracts in respect of the cost per building surveyed. So, after a few years, the contracts were reviewed. Two of the contractors were dispensed with, and the remaining two —

14. The Chairperson: After how long?

15. Mr O'Reilly: After four years: they worked from 1997 to 2001.

16. The Chairperson: Four years — do you understand why some people might think that the project lacked good practice and project management skills?

17. Mr O'Reilly: There was a need to understand what was happening. The contracts, as I said, were let for separate geographical areas. Differing numbers of properties were surveyed in each area, which had a significant impact on the net price per property surveyed in each of the contracts. During that first four-year period, the exercise was bedding down. The first full review of how the contracts and survey were working was undertaken only in 2001.

18. The Chairperson: Originally, the project was supposed to take 11 years, so four years would have been just under one third of the way through. Four years is a serious amount of time, never mind bedding in.

19. Overall, the Audit Office report gives the impression that this part of your Department does not have much of a managerial culture and that certain functions are not well managed. What actions have you, as permanent secretary, taken to strengthen management since the publication of the report in March 2011 last year? You have had over a year.

20. Mr O'Reilly: As you rightly highlight, we have been in receipt of the report for a year, but, of course, even before it was published, we were aware of the various issues and concerns being explored by the Audit Office during its review exercise in the Department. I will answer your question by quickly referring to the report's key findings and recommendations, which, to some extent, will allow me to outline what has been happening over the past year and even before that.

21. The first recommendation concerns improved targeting arrangements. Those have been introduced since 2007, when a fundamental review of the whole second survey exercise was carried out. More recent contractual work has included improved targeting arrangements before the fieldwork begins.

22. The second recommendation refers to prioritising work for survey activity. The recommendation is that the contract, which expires in 2013, should be reviewed to ensure that current procedures are built on.

23. The third recommendation is that NIEA engage more proactively with owners, particularly owners of buildings that are on the Built Heritage at Risk in Northern Ireland (BHARNI) register. That has been taken up more proactively over the past year through positive engagement with owners and, at the same time, taking enforcement action or issuing warning letters to owners when we feel that activity is not being properly taken forward.

24. The fourth recommendation deals with issues surrounding the funding of the grant scheme and whether we should introduce enhanced targeting arrangements. It refers to a formal weighting and scoring exercise. Fortunately, over the past year, as we have highlighted to the Committee, we have been able to maintain and increase the grant spend. However, the recommendation remains relevant because there are still potential issues in the future in relation to the funding available for that piece of work in the Department.

25. The fifth recommendation is:

"OFMDFM and NIEA work together to put formal processes in place to ensure that public bodies understand, and comply with, their management and reporting responsibilities".

26. That engagement has taken place. A new protocol for the care of the government estate was agreed by the Executive in February, and we intend to publish that next month. The Committee may want to come back to that later.

27. The second last recommendation concerns the need to review the operation of our enforcement databases in light of the Criminal Justice Inspection (CJI) report in 2007. A follow-up report by CJI was published in November 2011. As part of that review exercise with CJI, we have taken action to enhance the working of the databases in the planning portal to ensure that they fully comply with the enforcement needs of the Environment Agency. Again, you may wish to come back to that.

28. The final recommendation is that NIEA undertake a review to understand the full range of its management and costing information requirements. That work has been taken forward over the past year, and actions have been put in place. We can perhaps update the Committee by going through the report. Over the past year since the report was published, we have been carrying out work on all the recommendations. However, to some extent, that was building on work that was already in train, particularly since the significant review of the second survey exercise that was completed in 2007 in the Department.

29. The Chairperson: I appreciate that detail. Other members will delve into some of those areas as we go through the report today. This question might be hard for you to answer, but, of all the initiatives that the Department is working on, where do listed buildings come as a priority? How high up on your list is that issue?

30. Mr O'Reilly: It is a significant issue for the Department for a number of reasons. There is the intrinsic importance of the subject and the importance that all communities, regardless of where they are, place on their built heritage and built environment. However, there is also, as members will be aware, a significant interrelationship between the quality of the built and historic environment and our tourist potential and offering. Indeed, since 2008, a Historic Environment Strategic Forum has been in place and has met regularly under the chairmanship of the permanent secretary. I have been its chairman for the past couple of years. Over the past year, our preoccupation has been with the completion of a report on the economic value of the historic environment in Northern Ireland, and that exercise has included a highly detailed to establish the monetary value of the built estate and historic buildings in Northern Ireland. For the Committee's information, that group comprises colleagues from NIEA in the Department, the chief executive of the Tourist Board and representatives from the Historic Buildings Council and the Historic Monuments Council. It also includes representatives from external voluntary and other groups concerned with the built environment, including the Belfast Buildings Preservation Trust and the Heritage Lottery Fund. So we have a set of arrangements in place and are seeking to engage proactively with our colleagues in the voluntary sector and the non-governmental sector to ensure that the work on promoting, maintaining and improving our built heritage is taken forward in a co-ordinated way.

31. The Chairperson: Paragraph 4.4 of the report quotes the Planning Service:

"unauthorised works to, or demolition of, a listed building constitutes a Priority 1 case"

32. In the past, some resources were diverted from this area, but none of the Planning Service's business plan targets for enforcement relate to listed buildings. Maybe I am wrong, but that is what I take from the report. Will you explain the rationale for that apparent contradiction? If listed buildings enforcement is a priority 1 issue, it surely merits specific performance targets, but I see none.

33. Mr O'Reilly: Every listed buildings enforcement case is treated as a priority 1 case by the Planning Service. It is important to note that the number of listed buildings cases that come through for enforcement is, fortunately, a relatively small proportion of the total enforcement caseload in the Planning Service. Over the past three years, the Planning Service has opened more than 11,000 enforcement cases, which are cases involving enforcement activity or enforcement matters being investigated. About 100 of those relate to listed buildings, which is approximately 1%. That said, they are all treated as priority 1 cases because of their significance. So although there is no separate target for listed buildings, they are treated as an important part of enforcement activity in the Planning Service. Fiona will deal with the general point and provide some background.

34. Ms Fiona McCandless (Department of the Environment): Enforcement cases for listed buildings are treated as priority 1. However, other unauthorised developments, which could result in public danger, are also treated as priority 1 cases, as are those that could result in permanent damage, such as trees protected by tree preservation orders. Listed buildings are treated as high priority 1 cases, for which we have separate targets: for example, 95% of cases in which there has been unauthorised work to listed buildings should be inspected within three days, and 100% should be inspected within five days. The separate targets for priority 1 cases are included in our business plan.

35. The Chairperson: Mr O'Reilly, the 2010 report from the Public Accounts Committee on planning authorities states that money was diverted from this initiative. You said that it was a top priority, so why was money diverted from it? When other priorities come in, money is deflected from the initiative to them. It seems to be an easy target.

36. Mr O'Reilly: I gave evidence to this Committee on that report, and I recall the concerns expressed by the then members about enforcement activity in the Department generally and in the Planning Service in particular. Despite the various financial pressures that all Departments are facing, including the Department of the Environment, we have continued to place a particular emphasis on improving our enforcement activity across the Department, including in planning. The total number of staff working on enforcement activity, for example, is 44: 37 full-time and seven part-time staff. A decade ago, there were 14 working full time on enforcement activities. So we have increased by 30 the number of staff working on enforcement activity, and we have moved to a system of ensuring that those staff are located across the various planning offices in Northern Ireland, which means that they are close to where incidents and problems arise.

37. There are other parts of the Department in which we are also seeking to improve and enhance our enforcement activity, but that is a particular focus in planning. Despite other pressures, we have continued to increase the staffing resources allocated to that activity, taking account, in particular, of the concerns expressed back in 2010 by this Committee about enforcement.

38. Mr Copeland: Leo, Michael, Fiona and Manus, you are all very welcome. Michael, I have not seen you since we crossed swords over Loopbridge mill, if I remember correctly. That is a building site now but is to become a Tesco store. I confess to much preferring the old red-brick building.

39. I see from paragraph 2.3 that the first 10 years of the current survey of historic listed buildings progressed on a stop-start basis. The survey seemed already to be in trouble by 2002, but, for some reason, it was not until 2007 that you undertook to review its methodology. It strikes me that six years is rather a long time to decide to re-evaluate a survey that appeared to be in some trouble. The need for re-evaluation was glaringly obvious by 2001. Will you give us some idea of the thought process that delayed it for six years?

40. Mr O'Reilly: With members' agreement, I will highlight some initial points and then pass to my colleagues Michael and Manus, who were involved in the exercise. Indeed, Manus carried out the major review in 2007. From my reading of the background papers, I understand that a large amount of fieldwork was carried out by the contractors during the first phase of the survey exercise between 2001 and 2007. In other words, initial work was done to survey buildings. However, as I said, an overall survey exercise is not complete until that work is reviewed by staff in the agency and decisions taken on whether buildings should be listed. There is a process that follows the fieldwork stage, if I may put it like that.

41. Mr Copeland: Yes.

42. Mr O'Reilly: By 2001, quite a backlog of casework had built up. The fieldwork stage was complete, but there was a backlog —

43. Mr Copeland: Was that a resourcing or finance issue?

44. Mr O'Reilly: Primarily, it was a staffing or skills-based issue. As you will appreciate, that work requires staff with an architectural background or skills who know what they are looking at in individual buildings. Therefore, for a period of three or four years, most of the agency's focus was on trying to clear that backlog. I suspect that it was probably after that stage had been completed that the agency was able to consider restarting the survey and re-examine its contractual framework. Indeed, as appendix 3 to the report highlights, survey work restarted in 2004. However, the survey was again suspended in 2006, mainly because of the problems with letting a new contract. New contracts were advertised and bids came in, but, after consultation with internal audit teams, those bids were considered too expensive. We did not proceed with those contracts because we felt that they had increased in price so much that they did not represent value for money. A further review of the contracting arrangements was undertaken as part of the major policy review in 2010.

45. Mr Copeland: Were the tender conditions altered at that stage, or was that an attempt to get the same value for less money?

46. Mr O'Reilly: I think that it was an attempt to get best value.

47. Mr Copeland: I understand that.

48. Mr O'Reilly: What I think happened was that the prices that we were working on up to then had been sourced back to the letting of contracts in 1997 and 1998. In the intervening period, there had been a significant construction boom and there was lots of work for architects and other professionals, so the bid prices that came in were much higher than the Department expected. That was why it was decided not to proceed with that tranche of contracts. Instead, a further review was undertaken to seek to establish a more viable contract framework that would deliver better value for money.

49. Mr Copeland: I take it that that problem no longer exists.

50. Mr O'Reilly: The present contract was let in February 2010, with an average survey price per building of, we think, £350. That is a fixed-price contract, and we think that it represents value for money. However, as the report highlights, that contract will expire in 2013, so we are beginning a review exercise to consider the framework through which we will take forward further contractual arrangements in the subsequent period.

51. Mr Copeland: How much did you say that it costs per building?

52. Mr O'Reilly: £350.

53. Mr Copeland: Given the amount of work involved, that seems quite competitive, certainly compared with what some companies charge for personal capability work assessments. However, that is an issue for somewhere else.

54. Mr O'Reilly: I do not know whether my colleagues wish to pick up on any points that I may have missed.

55. Mr Michael Coulter (Northern Ireland Environment Agency): There was a scoping issue at the outset, and then we had to deal with a backlog of fieldwork produced by contractors. The focus was on making sure that we processed that fieldwork. If fieldwork is not processed rapidly enough, it becomes out of date, and changes may have been made to buildings — that was an issue in the first survey — and we have to go back and do it all over again. So we focused our effort, first, on processing the backlog. After we addressed that, we sought to establish new contracts. That said, throughout all the contracting, and despite the systematic pausing of the main second survey, we maintained the capacity for contractors to carry out ad hoc surveys. So if were informed that a particular building had not been listed or needed a second survey, we maintained the capability to do that in what were, effectively, emergency situations.

56. Mr Copeland: So that was a way of using the available resources as effectively as possible to ensure that the work that had been done was not wasted. It also allowed the process to move along as far as possible with the resources available.

57. Mr Coulter: Absolutely.

58. Mr Copeland: Chair, with your indulgence, I will be slightly naughty.

59. The Chairperson: That is not like you.

60. Mr Copeland: I am a carpenter and joiner by trade, and I was interested to note the inclusion of Prehen House in Derry/Londonderry on page 12 of the report. I was even more interested, although I have subsequently found out how the situation arose, in how a 17th century house could be described as early Georgian, given that the Georgian period did not start until the latter early half of the 1700s, by which time the 17th century had long departed. It is certainly on my list of buildings to visit on the basis of the early joinery work in the stables.

61. The Chairperson: Is that the latter early half, did you say?

62. Mr Girvan: He served his time there.

63. Mr Copeland: I cannot remember, but if I did, I am sure that the joinery work would be of a very high standard. I just could not understand how a 17th century building could be described as early Georgian. It would have to be fairly early, unless there were additions.

64. Mr Manus Deery (Northern Ireland Environment Agency): It is, in fact, an 18th century house: there is a misprint in the report. There was a 17th century house on that land, but as far as we know, Prehen is an eighteenth-century house.

65. Mr Copeland: I researched it: the bit that was left, the origins of the foundations, went back to the 17th century. It just struck me as confusing.

66. Paragraph 2.7 states that the survey is expected to be completed in 2020, which means that it will have taken 23 years. That is quite a long time. It was anticipated at the outset that the survey would take 11 years, so when the time frame was set, it must have been unrealistic. The update paper explains that there is now a new backlog of reports from 2011-12 that have not been processed by the Northern Ireland Environment Agency. To be honest, and forgive me for saying so, because I mean no harm, it does not exactly inspire confidence. Can you assure us that this survey will not go back to the stop-start rate of progress? What measures are you taking to ensure that it will be finished by 2020?

67. Mr Coulter: The issue is less that a backlog has built up and more that there is a processing time between what we receive and what we can process through to listings or delistings. There is a time lag, so we have a number of records in the office that are being processed through the system but not a backlog per se. Certainly, the number of records at any one time varies, but we are determined to put resources in place to ensure that we can maintain a flow that balances the resources that we have to buy in the contract survey of work in the field and the processing that can be done by staff in-house. I do not know whether Manus wants to add any more detail on that.

68. Mr Deery: The issue is that, in the past year, we had to divert staff to other areas, because the cutbacks at the beginning of the year meant that we thought that we would not have the necessary budget and that the second contract, would have to end. However, we received resources in-year and were able to survey the full amount that we had expected to in that year. We had to move the staff resources back to cover that. That explains why the figure is slightly higher than we would have expected at this stage. As Michael said, we are putting resources in place this year to make sure that that does not become a backlog as such.

69. Mr Copeland: Do you have any notion whether irreplaceable buildings are being lost because we have not given you sufficient resources? Is there any possibility of that? Not very far from my office, there is a Georgian terrace — in this case, genuinely Georgian — two of which appear to have some protection. However, it is my firm belief that the developer or the owner, had he the ability, would level the third one because it is dangerous and because of the cost of maintaining it. It strikes me that, on some occasions, we know the price of everything and the value of nothing. We will never be capable of recreating some of what is lost. I am asking for an honest opinion: have buildings been lost?

70. Mr Coulter: That is always a risk. However, as I was saying, even when we systematically paused the second survey, we maintained the capacity for ad hoc surveys by both contractors and in-house staff. If we receive any notification from whatever source, whether members of the public, colleagues in Planning Service, people in the voluntary sector, members of the Ulster Architectural Heritage Society (UAHS) — I think that I am right in saying that Rita Harkin is sitting just behind me today — we react. We go out and check out buildings, and if we consider them likely to meet the listing standard, we will go through the second survey process and seek to add them to the list. However, no system is perfect. There will always be a concern that we may lose buildings, but we use our best endeavours to ensure that we catch any such cases. We use any form of information that comes to us. We react to it and seek to save such buildings.

71. Mr McLaughlin: I have some appreciation of just how difficult it would be to have a comprehensive perspective on all the assets. The Ordnance Survey conducts continuous aerial surveys and regularly produces 3D maps, and so on. Do you link to those emerging technologies as well as maintaining your register? If you did, you could be specific in identifying where the buildings are and in responding to information from, say, the voluntary sector's preservation groups, which form around local areas or buildings of interest.

72. Do you work with building control officers? Is all that linked into the survey? It amazes me that the first survey took so long and that the second survey also seems to be running into difficulties.

73. Mr Coulter: Thank you for your understanding of the scale of the task. That is acknowledged in the report. In the second survey, we deal not only with the exterior of the buildings but, for the first time ever, we go into the interior. Through Planning Appeals Commission cases, we had learned many lessons about the inadequacy of the extent of our records, although the quality of what was produced was very good.

74. We use a great deal of Ordnance Survey mapping, but we focus more on historical mapping, which is useful for establishing where the older buildings are likely to be. When conducting the second survey, three basic areas are considered: the first group of buildings presented is of those already on the list; the second grouping is those that were considered for listing in the first place, and the third is those that surveyors find anew.

75. Mr McLaughlin: That is helpful. The Ordnance Survey work is valuable to Land and Property Services in detecting changes in the footprints of buildings, such as extensions, etc. It seems to me that that would have an application for you as well. You would be able to detect any unapproved work carried out to listed buildings.

76. Mr Coulter: Absolutely. I agree completely that it has merit in that regard. As the second survey continues and we make a new record of a building, we find any changes that have been made at that stage. That becomes a mechanism by which we advise our colleagues in Planning Service about enforcement issues.

77. Mr McLaughlin: So you agree that the Ordnance Survey process would be of assistance? I am looking for an assurance that you access the information available.

78. Mr Coulter: I do not think that we do, but Manus can provide more detail.

79. Mr Deery: Our current engagement with Ordnance Survey is through the demonstration on our website of our heritage of historic monuments and listed buildings. You can go on to our website and zoom into a part of Northern Ireland. The heritage features are highlighted on the Ordnance Survey maps, and information on them is available. As Michael said, different levels of maps are available. We have not engaged with Ordnance Survey on the means of identifying those buildings in the first place, and perhaps there would be some merit in doing so. Michael talked about responding to the voluntary sector and to any concerns that may be brought to us. We certainly respond to every listing query that comes to us.

80. At present, the survey is designed so that we cover one district council at a time. That means that we go to the district council; explain in advance what we intend to do; ask members to suggest buildings that might be of interest to them; and, through that, highlight to local voluntary societies the opportunity to suggest buildings. That is how we compile a list of buildings to give to our contractors.

81. We have had developing engagement with local building control departments. We found in Strabane, for example, that building control officers were going out to look at every building that we proposed to list and producing a report on them. They were consulting individual owners, not knowing that we also informed the owners. We have been able to work with building control and develop its awareness as it is looking at its role and how it develops. There is certainly scope there.

82. Mr McLaughlin: I think that Land and Property Services would admit that it could not carry out its function without that level of collaboration. I have a very pedantic mind, and I was wondering about the difference between preservation and conservation. Is it a legal definition? If you stop people destroying the property, is that the preservation end of it?

83. Mr Coulter: That is debated in professional circles, and, for every professional you ask, you get a different view. However, for what it might be worth, as director, I say that preservation is where you seek to retain things with an absolute minimum of change, and conservation is where you accept positive change. In that regard, we use scheduling legislation to protect archeology, where we seek to have no change. However, with listed buildings, we use conservation-based legislation that allows for the fact that, because you want to keep a structure or building in use, it may be entirely appropriate to add an extension or toilets or do maintenance work. That is a personal definition, if that helps.

84. Mr McLaughlin: It does help. Thank you.

85. Mr Coulter: I will go back to your questions on building control. We joined in with annual meetings with building control over a number of years, and we have had joint seminars that have specifically focused on buildings at risk. We have, as Leo said earlier, an owners forum, and we have met owners for four years in a row. Between 300 and 350 owners come along to those sessions, and we are joined on those days by a building control officer, who provides information from the building control side. There is quite a bit of rapport. I was speaking to Fiona about enforcement cases, and Planning Service uses Ordinance Survey (OS) information on rear extensions and so on as part of that action.

86. Ms McCandless: We engaged recently with building control on enforcement cases, and we sometimes rely on members of the public and people from other Departments or building control to advise us of breaches of planning control. We have provided building control officers with access to all our listed buildings and to electronic copies of all our conservation area maps so that they are aware if a building is in a conservation area or is listed.

87. Mr Coulter: We have gone further than that and have given the Northern Ireland Fire and Rescue Service access to our databases so that, if it is dealing with a fire in a listed building, it knows that it is a listed building and that it is of more concern. We have quite a positive rapport there.

88. The Chairperson: People usually try to stop answering questions when they are in front of us, but you are going the opposite way.

89. Mr Copeland: Paragraphs 2.10 and 2.11 show that the contract management of the survey until 2007 could, by any standards, safely be described as poor. There was no fixed price for the work, and contractors were paid an hourly rate, and, as a result, the whole process was effectively being run, to a degree, by the contractors, and you had no overall control of costs. Why was there difficulty in getting to grips with the situation until long after the survey had started? Do you believe that the agency now has the necessary management skills in place to prevent a reoccurrence of how we see it, which is maybe not how you see it?

90. Mr O'Reilly: I will respond to your last question and perhaps ask a colleague who was around at the time when the second survey was getting under way to come in after. Since the review was carried out in 2007, we have been very conscious of issues of cost control, and that is why, although it has delayed things, we have taken time to try to put in place a contracting framework that guarantees sufficient quality of survey work and ensures that it is done at a reasonable cost to the public purse. As we said, the most recent contract for the survey has been agreed on a fixed-price basis at an average price of £350 per building surveyed. So, in more recent years, we have sought to address, at an earlier stage, the contractual difficulties that you have identified.

91. Figure 5 shows that there were significant variations in the cost per building surveyed, which is related, in part, to the size of the individual contracts. In general terms, the larger the number of buildings in a contract, the lower the cost per building surveyed. However, you can see also that that was not the case with contractor C and that, in fact, a relatively small number of buildings were surveyed at a very low cost. Michael can outline the reasons for those variations and explain what happened in the early stages.

92. Mr Coulter: Each of the four contracts that were issued were tendered, and various rates came in. There were issues around how many buildings were in a particular area. There may have been questions around how many surveys particular contractors carried out. The hourly rate reflected the fact that we had never before been involved in the process of being inside buildings and making such an extensive record, etc. On reflection, it is good to be able to look back on those figures. On average, the cost per record that we ran through in those times, at an hourly rate, was about £350. Even now, when we go through fixed-price tendering, the ballpark price per record is still £350.

93. Mr Copeland: I can follow that logic.

94. Mr McQuillan: Thank you for your answers so far. Paragraph 2.13 states that 60% of the buildings that were surveyed were not suitable for listing, and it cost £1·1 million. I appreciate that you now have better records, as you said, but do you not think that it was a waste of taxpayers' money to pay that sort of money to get a few records? A high percentage of buildings were not listed.

95. Mr O'Reilly: We agree with the broad conclusion: the 60% rate is too high. Since 2007, as the new contracts have been let and as the contractors prepare to move into a new ward or district council area, a pre-survey exercise is carried out in the agency to seek to narrow down the number of buildings that will be surveyed to ensure that there will be a closer focus on the buildings that are likely to merit listing or attention. The figures are accurate; they cover the full period of the second survey activity to date. Since 2007, the ratio has moved to 50:50, but our objective is to get it to 60:40 in the other direction. That is what we seek to do, and we are beginning to achieve some success in reducing the percentage figures that are quoted in the report.

96. The purpose of the survey is, of course, to identify buildings, particularly new buildings, that may be suitable for listing. To some extent, therefore, there will always be a proportion of buildings that you survey that you conclude are not suitable for listing. We would not expect —

97. Mr McQuillan: It should be a smaller percentage.

98. Mr O'Reilly: It should be a smaller percentage. It is roughly 50:50 at the moment and has been so for the past few years. It should be down to 40%.

99. Mr McQuillan: You mentioned the pre-survey. Who carries that out?

100. Mr Deery: It is a scoping survey. The current contract was let in 2010. The contractor scopes the area. He knows that he has to survey the listed buildings because, even if we are going to de-list them, we need a full survey to be able to justify that decision. He scopes the area and then brings in the results of that. That is his initial historical review and his initial drive-past survey, which identifies potential buildings. He then goes through that with us, and we agree with him the buildings that he is going to survey. In the past, we relied more on his professional judgement; in the 2008 and 2009 surveys, the contractor came to us with what he felt were the borderline ones. We felt that, even with that, there was still too big a difference. As Leo said, the ratio of 50:50 is the result of the two tests contracts in the surveys of Cookstown, Strabane, Omagh, Newtownabbey and Carrickfergus. Currently, we are aiming much closer to that 40% figure.

101. Mr McQuillan: You have nearly answered my second question, but I will put it to you anyway. Paragraphs 2.19 to 2.21 tell us that two successive internal audits recommended a more targeted approach to survey work. That was rejected by NIEA. Paragraph 2.24 indicates that the Audit Office also expressed the view that resources should be better targeted. Can you explain to the Committee why you rejected internal audit recommendations on two separate occasions and whether you are now adopting a more targeted approach? I take it that you are.

102. Mr Deery: The recommendations in the first audit report were largely accepted as part of the 2007 review and were worked into the test contracts. The principal recommendation was to move away from hourly rates to batch processing. The second audit report concluded that if the test contract proved to be unsatisfactory, a more targeting approach should be carried out. The results of the Cookstown survey, which was the first test contract, were very much on the money in respect of what we were expecting. At the same time, we let the ad hoc contract, which happened after that auditor had reported. That came back with a cost per record of £840. So, the decision was between either proceeding with a £350-per-record survey but surveying a wider number of buildings or having a much more focused survey. The danger with a much more focused survey is that you start to go towards the ad hoc end of the spectrum, in that you have to go back to an area and carry out more individual historical research, which involves more travel time.

103. Our view, at the time, was that the test had proven itself. I suppose the way that we are addressing the targeting approach is by being much stricter with the contractor at the scoping stage by ensuring that that is well focused. One of the other issues with a contract approach is that there is a danger that you might have a new contractor and, therefore, another training period. So, having that scoping level ensures that there is no slippage if there are different contractors at an early stage.

104. Mr McLaughlin: Hello, Leo. Paragraph 3.3 says that the Environment Agency did not establish any specific objectives or performance measures for the grant scheme at any stage since its inception in 1974. In effect, it was paying out over £3 million a year with no specific targets, performance measures or specific objectives. So the question is this: how could you ensure that you were using the grants effectively if you did not set out in advance exactly what you expected to achieve? The obvious follow-up question is whether now, some 14 months after the audit report, you have addressed that issue and whether those objectives are now in place.

105. Mr O'Reilly: As the report reflects, the emphasis of the grant scheme has been on, in a sense, ensuring quality outputs, in other words ensuring that the work carried out on individual buildings in receipt of grant support is done properly and to the right standard before that support is paid to the owner of the building. To that extent, there has been monitoring, but it was done case by case.

106. I suppose, from my analysis, the reason why there has not been an attempt to look at more general impacts on the total stock of listed buildings is that, in any one year, an average of, for example, 150 individual listed buildings will receive grant aid support. That is positive, but, out of the total stock of listed buildings in Northern Ireland, it is a relatively small proportion. So, it is only going to be over a considerable period of time. For example, we estimate that over the past seven years, just over 730 buildings have been in receipt of grant aid support, which begins to bring you up towards 8% or 9% of the total stock of listed buildings that have now received some form of grant aid over that period. That, in a sense, is an explanation of the approach adopted previously.

107. On the latter part of your question about what has happened since last year, we have decided, this year, to carry out a baseline survey of the general condition of the listed building stock in Northern Ireland using statistical techniques. I am told that if we carry out a survey on the general condition of a random selection of approximately 2,000 buildings, that will give us a fair idea of the total standard of the stock across 8,500 buildings. So, that exercise will be carried out this year. A similar type of exercise was carried out in 2000, so the results of the exercise this year will give us something to compare with the previous one.

108. I think that the answer to your question is yes. I can see people thinking that, it is OK; they understand that we have to look at individual buildings, but they may still wonder whether what we are doing is having some sort of overall beneficial impact on the stock. Having looked at this issue since we received this report last year, we will carry out this baseline survey this year to seek to establish the general condition of listed buildings in Northern Ireland at the moment.

109. Mr McLaughlin: I presume that is not intended to be a 'Groundhog day' type of operation, and that we are looking at the general condition of buildings that we are trying to conserve and whether the grants are having this impact.

110. Mr O'Reilly: We would be certain of that in the cases where a grant is paid, because there is architectural involvement from colleagues in the NIEA's historic buildings unit in each and every one of those schemes. They will have an input and, before the grant is paid, they review the quality of the work when it has been completed. I suppose the difficulty is that a large number of listed buildings are untouched by grants from one year to the next. The question is what is happening to the condition of those buildings. That question is unanswered, but we hope that the baseline survey this year will help us to get some idea.

111. Mr McLaughlin: That could be germane to the discussion or the consideration, particularly with other Ministers who are competing for financial resources. If you can demonstrate that, because you have set out objectives and have applied the grant regime to achieving that and measuring the beneficial impact, you can address those that fall outside the scheme; those buildings that receive no grant aid whatsoever but could possibly benefit, before we get to the stage of having to spend large sums of money.