Report on the Review of Workplace Dispute Resolution

Committee: Employment and Learning

Session: 2008/2009

Date: 24 June 2009

Reference: NIA 45/08/09R

ISBN: 978-0-339-60285-4

Session 2008/2009

Third Report

COMMITTEE FOR EMPLOYMENT AND LEARNING

Report on the

Review of Workplace

Dispute Resolution

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the committee

relating to the report and the minutes of evidence

Ordered by the Committee for Employment and Learning to be printed 24 June 2009

Report: 45/08/09R (Committee for Employment and Learning)

This document is available in a range of alternative formats.

For more information please contact the

Northern Ireland Assembly, Printed Paper Office,

Parliament Buildings, Stormont, Belfast, BT4 3XX

Tel: 028 9052 1078

Membership of Powers

The Committee for Employment and Learning is a Statutory Departmental Committee of the Northern Ireland Assembly established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of Strand One of the Belfast Agreement and under Standing Order 46 of the Northern Ireland Assembly. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Department for Employment and Learning and has a role in the initiation of legislation.

The Committee has power to:

- consider and advise on Departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- approve relevant secondary legislation and take the Committee stage of relevant primary legislation;

- call for persons and papers;

- initiate inquiries and make reports; and

- consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister for Employment and Learning.

The Committee is appointed at the start of every Assembly, and has power to send for persons and papers and records that are relevant to its inquiries.

The Committee has 11 members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, and a quorum of 5. The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Ms Sue Ramsey (Chairperson)

Mr Robin Newton * (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Alex Attwood Mr Paul Butler

Rev Dr Robert Coulter ** Mr Alex Easton ***

Mr David Hilditch *** Mr William Irwin ***

Ms Anna Lo Mr David McClarty

Mrs Claire McGill

Mr Alastair Ross replaced Mr Jim Wells on 29 May 2007

* Mr Robin Newton replaced Mr Jimmy Spratt as Deputy Chairperson on 10th June 2008

** Rev Dr Robert Coulter replaced Mr Basil McCrea on 15 September 2008

*** Mr Alex Easton, Mr David Hilditch and Mr William Irwin replaced Mr Nelson McCausland, Mr Alastair Ross and Mr Jimmy Spratt on 15 September 2008

Table of Contents

List of abbreviations used in the report

Report

Appendix 1:

Minutes of Proceedings relating to the report

Appendix 2:

Appendix 3:

Written Evidence Submitted by Witnesses

Appendix 4:

Appendix 5:

Appendix 6:

Appendix 7:

List of Abbreviations used in the Report

ADR - Alternative Dispute Resolution

BERR - Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform

CBI - Confederation of British Industry

DEL - The Department for Employment and Learning

ECNI - Equality Commission for Northern Ireland

FSB - Federation of Small Businesses

HR - Human Resources

LRA - Labour Relations Agency

NIC-ICTU - Northern Ireland Committee, Irish Congress of Trade Unions

NIAO - Northern Ireland Audit Office

OITFET - Office of the Industrial Tribunals and the Fair Employment Tribunal

SME - Small and Medium Enterprise

‘the Committee’ - Committee for Employment and Learning

‘the Department’ - Department for Employment and Learning

‘the Minister’ - Minister for Employment and Learning

‘the Gibbons Review’ - “Better Dispute Resolution - A review of employment dispute resolution in Great Britain"

Executive Summary

The Department for Employment and Learning (‘the Department’), in February 2008, undertook a policy review of statutory employment dispute resolution procedures prompted by stakeholder concerns of the existing arrangements and by the findings of the Gibbons Review – “Better Dispute Resolution - A review of employment dispute resolution in Great Britain" – published in March 2007.

In May 2008 Sir Reg Empey, Minister for Employment and Learning (‘the Minister’), agreed to the establishment of a steering group tasked with assisting in the development and oversight of meaningful public consultation on key issues around the resolution of employment disputes. In October 2008 the Department published its report on the findings of the pre-consultation.

The Committee for Employment and Learning (“the Committee") welcomes the opportunity to progress this extremely important and necessary policy area in conjunction with the Department, both pre- and post-consultation, and feels that a coordinated approach to addressing the issues will best serve the needs of employers and employees alike.

The objective of the Committee’s review is therefore:

“To collate and consider the opinions and views of relevant stakeholder organisations on a way forward for workplace dispute resolution in Northern Ireland".

In meeting this objective, the Committee received briefings from Departmental officials and also took evidence from a range of key stakeholders.

Based on the evidence received, and taking on board the views of Members, the Committee feels that there is a need to develop and promote a culture of early dispute resolution as opposed to seeking legal redress through the tribunal system as the most appropriate approach.

The Committee agreed that there is a need to reform the current statutory procedures, but would emphasise the importance of ensuring that the revised system is properly thought through and represents a synergy of the best of the current system with the best of the options for change, to develop a system that meets our needs for resolving workplace disputes while allowing greater access to justice and improved efficiency. The new system should ensure the protecting of the rights of individuals and employers, and their access to justice.

The Committee agreed fully with those who gave evidence that Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) should be promoted as the most appropriate alternative to tribunals in order to protect the privacy of those involved and so ensure the pursuit of a faster, flexible and more cost effective means of settling a grievance, especially given the current economic climate.

The Committee agreed with a number of witnesses who stated that the role of the Labour Relations Agency (LRA) should be extended to cover a wider range of advice and ADR services and that there is a need for the refocusing the LRA’s resources in order to provide such extended services.

The Committee also agreed with those witnesses who identified the importance of the tribunal system, but also took on board the concerns that employers and employees have around that system.

The Committee feels that there is a need to ensure that dispute resolution is made simpler and less bureaucratic for both employer and employee and that a revised system does not simply replace one set of complex and confusing rules and regulations with another that are not user-friendly.

The Committee strongly believes that the provision of more accessible information and the promotion of a clearer understanding of employer and employee rights and obligations, by all those involved, are key to the success of any revised system. Lack of accurate information and clear instructions for those participating in the current structures was a recurring theme raised by all of those who gave evidence and this is an issue that needs to be addressed in order for the revised system to be meaningful.

The Committee is of the opinion that the public sector plays an extremely important role in the process, firstly, by ensuring that it leads the way in developing best practice models and, secondly, by leading by example through implementing these models.

Introduction

Background

1. The Department, in February 2008, began a policy review of statutory employment dispute resolution procedures. The review was prompted by stakeholder concerns surrounding the existing arrangements and by the findings of the Gibbons Review. This review, commissioned by the Department of Trade and Industry (renamed the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform or ‘BERR’ and now the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills), was published in March 2007 and entitled “Better Dispute Resolution - A review of employment dispute resolution in Great Britain". The report can be accessed at http://www.berr.gov.uk/files/file38516.pdf.

2. The purpose of the Department’s pre-consultation stage of its review was:4.

- To determine whether there is appetite for reform of dispute resolution procedures in NI;

- To gain an initial steer on the appropriateness locally of the proposals contained in the Gibbons Review; and

- To invite suggestions of other options which might be worth investigating. Stakeholders were asked to consider whether there are lessons to be learned from dispute resolution best practice elsewhere in the world.•

3. In May 2008 Sir Reg Empey, Minister for Employment and Learning (‘the Minister’), agreed to the establishment of a steering group tasked with assisting in the development and oversight of meaningful public consultation on key issues around the resolution of employment disputes. In October 2008 the Department published its report on the findings of the pre-consultation.

4. In November 2008, Departmental officials briefed the Committee on the rationale behind the pre-consultation exercise and also on the findings of that exercise. This briefing to the Committee prompted its own review of Workplace Dispute Resolution with an aim of reporting its views to the Department in advance of the Department completing its public consultation.

5. The Committee welcomes the opportunity to progress this extremely important and necessary policy area in conjunction with the Department, both pre- and post-consultation, and feels that a coordinated approach to addressing the issues will best serve the needs of employers and employees alike.

Review Objective

6. The objective of the Committee’s review is:

“To collate and consider the opinions and views of relevant stakeholder organisations on a way forward for workplace dispute resolution in Northern Ireland".

7. In meeting this objective, the Committee received briefings from Departmental officials and also took evidence from a range of key stakeholders.

The Committee Approach

8. A methodology based on evidence gathering (oral and written) was used as the basis for the Committee’s review programme. Written and oral evidence was gathered from:

- The Department;

- Labour Relations Agency (LRA);

- Federation of Small Businesses (FSB);

- Equality Commission for Northern Ireland (ECNI);

- Confederation of British Industry (CBI);

- Northern Ireland Committee, Irish Congress of Trade Unions (NIC-ICTU); and

- Law Centre (NI).•

9. All of these organisations, with the exception of Law Centre (NI), are represented on the Department’s consultation steering group.

10. Submissions received and minutes of evidence are annexed to this report.

Consideration of evidence

11. From the outset of the Committee’s review it was made clear that the Minister and his Department did not have a preferred model for dispute resolution and that the Department’s consultation provides the opportunity to develop a bespoke local system of workplace dispute resolution, if deemed appropriate. It was also made clear that the findings of the Gibbons Review may not necessarily fit the needs of local employers and employees, especially given our high percentage of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and also the high degree of reliance on the public sector compared to elsewhere in the UK and Ireland.

12. During the evidence gathering process, the Committee was made aware of a number of issues of concern emerging from the majority of evidence put forward.

The need to promote a culture of early dispute resolution

13. The need for a change in how employees raise grievances and how employers deal with complaints was identified by the majority of those who gave evidence to the Committee. All too often the automatic approach is to seek legal remedy. This approach almost always escalates the problem to the point where any attempts at resolution is impossible.

14. There is a much greater tendency here to pursue litigation than elsewhere and there is also a greater tendency to link employment related issues with discrimination. The Committee would agree that this mindset needs to be changed.

15. The Department’s pre-consultation identified differing views on the need for a system focused on the promotion of employment relations as opposed to a rights-based system, which gives employers ready access to the legal system. It was agreed that such systems are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

16. A number of witnesses, and in particular the FSB, pointed out that in cases where a dispute is not dealt with prior to tribunal the costs incurred can cause the company to go out of business, especially if compensation must be paid. This is a situation that must be avoided at all costs and the Committee agreed with witnesses that alternatives to such terminal effects need to be established and encouraged.

17. Bearing these points in mind, and taking account of the cost implications and the stress involved in pursuing legal remedy, the Committee would strongly agree that there needs to be a cultural change towards a position where individuals and employers see the courts as the last resort and not the first course of action when a dispute arises. The benefits of tackling a problem, if possible, as close to its point of origin in the workplace needs to be promoted. Alternative options need to be put in place and employees and employers need to be made aware of their existence and of the assistance that is available to help resolve a dispute before there is any thought of legal action.

The need to retain, modify or repeal the statutory procedures

18. The current statutory procedures were introduced in England, Scotland and Wales in 2004, and in Northern Ireland in 2005. In 2006 a review of these procedures, The Gibbons Review, began; the review, which recommended the repeal of the procedures, did not cover Northern Ireland. The review also recommended the introduction of an Employment Bill, which was granted Royal Assent on 13th November 2008.

19. The Committee welcomed the Department’s approach whereby, although the Act repeals the statutory procedures in England, the consultation will seek the views of respondents as to whether the procedures here should also be repealed. The CBI expressed the view that, unless there were obvious benefits to the economy of acting otherwise, then we should follow the employment legislation that is brought forward in England. This is an issue that will perhaps be developed further in the Department’s consultation, but the Committee is of the opinion that the most appropriate system should be developed, and if this is in keeping with proposals in England then it would be appropriate to follow that legislation; however, it should not be adopted as an easy alternative to bringing forward legislation locally.

20. A number of witnesses highlighted that, although some feel that the “three-step procedure" which an employer must currently pursue with an employee in order to dismiss that employee should remain, the majority feel that it should cease. Currently an employer must first notify the employee in writing of the intended dismissal. Secondly, the employee can then ask for a meeting about the dismissal, and, thirdly, the employee can appeal, and a meeting must be held.

21. The Law Centre (NI) is in favour of retaining the statutory three-step procedure for disciplining and dismissing staff as they feel that it is simple and well understood by the majority of employers. NIC-ICTU reiterated this point in its evidence to the Committee. The Law Centre (NI) feels that removing the three-step procedure might lead to uncertainty and has the potential of cases for unfair dismissal being brought before the courts that would not otherwise have been brought. The FSB and the CBI expressed their desire to see this procedure repealed. The CBI, among others, is of the view that the procedure is too formal and that it often exacerbates problems that might well be better dealt with informally. Law Centre (NI) felt that the statutory dispute resolution procedures need to be reviewed. They are of the belief that the statutory grievance procedures are complex and confusing and should be removed. NIC-ICTU also felt that the grievance procedures are of a level of complexity that means people automatically have to seek legal assistance. The Committee would agree with this opinion.

22. Pay-related disputes are often a cause for disagreement between employer and employee and the Committee feels that, bearing in mind the apparent need to revise the procedures, there needs to be a mechanism put in place for the resolution of pay-related disputes. The LRA identified a need to reform how bulk or multi-cases, such as equal pay claims, are handled. Their approach to dealing with such cases on a pre-claim basis is to be welcomed, thus avoiding the hugely expensive, resource intensive and time consuming problems that these types of cases cause.

23. The Equality Commission emphasised the importance of ensuring that any reform must ensure that an individual’s rights under anti-discrimination legislation are not infringed and that a revised system must not limit or deny access to justice. The Committee would concur with this view but would emphasise that this should also extend to the employer. Law Centre (NI) put forward the view that, in reforming the system, the issue of access to rights of the individual should be kept to the forefront. Again, the Committee is in agreement with this opinion but it should also extend to the employer. The Committee would strongly agree with the view of Law Centre (NI) that this is an important opportunity to reform the system and that it should amalgamate the best of the current system with the best of the changes in England to develop a system that meets our needs for resolving employment rights disputes and allows greater access to justice while improving the efficiency of the system.

The role of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Techniques

24. It was apparent to all who responded to the Gibbons Review and to the Department’s pre-consultation that employment law needs to be simplified. However, simplifying the law can be an arduous process. The promotion of early dispute resolution practices, without the need to get involved in employment law, is seen as a more appropriate alternative.

25. In any dispute, the privacy of the individual involved is often of utmost importance and the Equality Commission identified the importance of ADR from this perspective. Not everyone wants a dispute to become public. Private resolution is extremely important to many but the outcome must be meaningful to all parties concerned. The Committee would agree with this statement.

26. An opinion that was shared by the witnesses who gave evidence to the Committee, and with which the Committee agrees, is that ADR is now a more pressing issue given the current economic climate whereby employers and employees alike require a faster, less expensive, alternative to the tribunal system.

27. ADR is a more flexible option than tribunals and it can often be used to reach an outcome that is acceptable to all involved and that helps to preserve the employment relationship. Tribunal is rigid and usually results in either, or all, parties being left dissatisfied. The CBI also believes that resolving a dispute in the workplace promotes good employee relations and it believes that procedures to deal with disputes should be fair and consistent. NIC-ICTU pointed out that the current system has no means by which to repair working relationships. The Committee feels that preservation of the working relationship should be encouraged.

28. Law Centre (NI) strongly supports the exploration of ADR options for certain employment disputes, but is of the view that ADR might not be appropriate for all disputes, for example, when an employer is considering dismissal of an employee.

Early neutral evaluation

29. Law Centre (NI) discussed the possible use of early neutral evaluation as a type of ADR that assists in the identification of claims that do not have merit or a defence. This form of ADR could either resolve the issue or help to identify an alternative means by which to resolve it.

Mediation

30. There needs to be a move towards the involvement of independent mediation, at an early stage, to try to resolve a situation before it has the opportunity to move to the stage of legal redress. Such an approach of independent mediation helps to remove doubts that an employee might have in the independence or objectivity of their employer’s internal processes. Concerns were raised that mediation is not regulated and it was agreed that this should be the case. Law Centre (NI) put forward the idea that pilot schemes should be put in place to ascertain the most appropriate form that mediation should take and how it should be run. The Committee would see this as a sensible approach. It was suggested by the LRA that in-house mediation services should be provided by the public sector, and also by larger companies in the private sector. The issue of mediation provision in the SME sector was also raised as an issue that needs to be addressed.

Arbitration

31. Law Centre (NI) sees arbitration as the final form of ADR and as an alternative to tribunal and feels that it should be considered separately from other types of ADR, such as mediation and early neutral evaluation. The LRA currently offers arbitration but this is very limited and rarely used, it can only be used for claims of unfair-dismissal and flexible-working claims. This needs to be made less rigid and needs to be promoted as a quicker, informal alternative to tribunal.

Rights Commissioners

32. NIC-ICTU, in evidence to the Committee, were highly supportive of the Rights Commissioner system that operates in the Republic of Ireland as they feel that it is voluntary, non-adversarial, faster, easily accessible and non-legalistic in its approach; they feel that it should be the first option if a dispute arises. They would argue that a Rights Commissioner system (under the auspices of the LRA), followed by conciliation through the LRA, and finally an appeals mechanism to the industrial court or employment appeals tribunal should be the appropriate route to address a dispute.

33. Rights Commissioners, according to the CBI, might not be beneficial on account of the hasty informal nature of the hearings. They also feel that some cases come before the Rights Commissioner that would be more appropriately dealt with administratively. They would also have criticisms of the lack of power held by the commissioner to dismiss a case in the event of the claimant not attending, the process in the Republic of Ireland is for the case to be automatically referred to the Labour Court; the CBI feels that this is a waste of the commissioner’s time and that it is a flaw in the system.

34. The Committee would be of the opinion that if such a system were to be considered then, after further investigation and evaluation of the Republic of Ireland system, it should be developed and rigorously tested to ensure that it best meets the needs of all of those involved in the process.

The role of the Labour Relations Agency (LRA)

35. The LRA is the primary deliverer of a range of ADR techniques aimed at early workplace dispute resolution but, as mentioned earlier, this is not often used. Law Centre (NI) commended the LRA on the conciliation service that it offers and they would wish to see, firstly, an expansion in the use of conciliation prior to submitting claims and, secondly, the raising of awareness of the potential of using conciliation at the pre-claim stage. In evidence to the Committee, the LRA felt that the requirement when a tribunal case is lodged to only offer conciliation for up to 7, and on occasion 13, weeks should be reviewed or possibly removed thereby allowing attempts to resolve the problem right up to the time of the tribunal. The Committee agrees with this approach.

The role of employment-related tribunals

The need to retain the tribunal system

36. Law Centre (NI) rightly pointed out that there needs to be access to justice in order to enforce legal rights before an impartial tribunal or court. The CBI and the Equality Commission believe that access to the tribunal system is also necessary to address legitimate claims that cannot otherwise be adequately resolved. The Equality Commission identified the significant impact that tribunals have had in the development of case law. Most consultees to the Department’s pre-consultation, and most witnesses who gave evidence, recognised the need for the tribunal system but as a last resort. The Committee were in agreement with these views.

Concerns raised by witnesses and consultees

37. It cannot be argued that the formal tribunal process is there as a mechanism to protect employers and employees alike but it can often act as a deterrent instead of providing the protection that is its aim. A range of issues were raised as reasons for claims not progressing to tribunal or for their not being appropriately dealt with when they reach the tribunal stage.

- Lack of Advice

Law Centre (NI) identified the basic problem with the system as being, in their opinion, the lack of advice and they would welcome the expansion of the provision of impartial advice, such as that provided by the LRA.

The forms that need to be completed in relation to tribunals need to be simplified; appropriate guidance should also be developed to assist in completion of the relevant paperwork. Guidance on grievance and discipline procedures should also be provided.

- Cost and anxiety

The attendance before a tribunal, and the cross examination by lawyers, often deters individuals from pursuing their grievances and they feel that the final result is not worth the stress involved.

Attendance can also take a great deal of time as cases might not start when scheduled and the actual hearings can last for a number of days. Many small employers and individuals simply cannot make themselves available for prolonged periods; this is also a deterrent to the system.

The process can be extremely costly and this is seen as a deterrent for many to pursuing genuine grievances. Legal Aid is not available to take claims to industrial tribunal and there is a lack of any tribunal representation service. Unless an individual has the backing of a trade union, or can manage to avail of the limited assistance available from the Equality Commission (for discrimination cases only) or the Law Centre (NI), then they have very little access to directed legal assistance.

The cost of the hearing itself is also a major barrier given that, irrespective of the result, claimants who engage a solicitor might still have to meet their own legal costs, which can often be more than the case is worth. More funding to organisations, such as the Law Centre, to provide advice would mean a move towards genuine cases actually proceeding to tribunal, if felt that pursuit was worthwhile, and would also assist in identifying cases that are without merit or defence.

- Perception of the system

Perception of the tribunal system is an issue for employers. The FSB expressed the need for small businesses to see the legal system as being neutral and not on the side of the employee.

- Fairness

The FSB expressed the need for small businesses to be treated fairly by tribunals, particularly in relation to them possibly not following model practices as a result of their not being aware of them, or being able to access them. This has resulted in many cases being dismissed on technical grounds. Conversely, Law Centre (NI) feels that it is the employee that is disadvantaged by the tribunal system. The CBI and NIC-ICTU also raised concerns, similar to the FSB and Law Centre (NI), regarding the ability of the tribunal system to treat employers and employees unfairly as a result of technicalities regarding model practices. All, however, agree that the system is too legalistic, complex and expensive and should not necessarily be viewed as the most appropriate way to resolve issues. The Committee also agreed with this view and felt that inexperience and lack of legal understanding should be taken into account by the court.

Improving the tribunal system

38. The Committee agreed that there is a need to promote the work of the LRA with regard to pre-lodging of tribunal proceedings. It also agreed that a more joined-up approach is needed between the LRA and the Office of Industrial Tribunals and the Fair Employment Tribunal (OITFET) although some concern was raised around any suggestion that industrial tribunal and fair employment tribunal should be merged. The Equality Commission discussed actions by the President of OITFET to reduce the time taken from case lodgement to hearing and this is to be welcomed.

39. The LRA identified the fact that a high proportion, 80%, of tribunal proceedings lodged are resolved prior to hearing. This figure is encouraging but more is required to firstly reduce the actual number of claims lodged and secondly to increase the percentage that are addressed prior to hearing.

40. It was suggested by a number of witnesses that tribunals should have sufficient powers to deal with weak or vexatious claims; this is a sensible approach but caution needs to be exercised as the definitions of weak or vexatious may be open to interpretation. The experience of the Law Centre (NI) is that vexatious cases should not be a driver of policy as the number of such cases is very small, they believe that the need for proper legal representation is a more appropriate driver of policy. The Committee would be in agreement with this view.

41. The LRA identified the need to encourage tribunals to play an active role in early case management. It also identified the need for the simplification of employment law.

Issues surrounding employment regulations

42. A number of witnesses felt that the procedures introduced in 2005 have reduced the possibility of early resolution and grievances now seem to be formalised at a much earlier stage than prior to their introduction.

43. The Committee felt that there is a need to reduce the amount of government red tape and bureaucracy that surrounds employment regulations and the dispute resolution processes. It was discussed as to how complex and legalistic the current system is and it was agreed that there is a need to simplify this to make it easier to understand for employers and employees. Many SMEs are reluctant to employ staff on account of the burden of excessive regulations and bureaucracy and by their lack of confidence when dealing with employment law. This reluctance has a knock-on effect on the local economy.

44. The FSB pointed out that a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to dispute resolution is not the best way forward for local businesses: SMEs are not equipped in the same way as larger companies and the public sector to resolve disputes. That said, the size and resources available to a company should not be a deciding factor as to how best to resolve an issue. NIC-ICTU pointed out that any system should be equitable, irrespective of the size of the company, and should not discriminate against small companies that do not have the same Human Resources (HR) expertise or financial backing as larger companies and the public sector. The Committee would strongly agree with this opinion.

45. All too often employers, especially small employers, are raising concerns over the complicated laborious process of meeting their obligations under ever-changing employment regulations. The Committee felt that good practice models and guides need to be developed to assist employers in meeting their obligations to employees as laid down in employment regulations.

46. The LRA currently provides a service to small companies whereby they assess the company’s disciplinary and grievance procedures and advise on changes or improvements. This is expensive in terms of staff resources but additional funding could help to improve this service. They also host a range of workshops and seminars aimed at SMEs to address changes or improvements to their procedures. This is seen to work well, feedback received is extremely positive and the Committee would hope that these will continue. The refocusing of the LRA’s resources to promote theses initiatives would go some way to address shortcomings that small businesses have in relation to meeting their obligations.

Lack of Information

47. The Committee agrees with the Department’s suggestion that a “handbook" for employers that addresses basic employment rights should be developed, in conjunction with appropriate stakeholders such as the FSB. The FSB agreed with this suggestion and felt that it could be promoted as a benefit to employers and employees, as opposed to another form of regulation. Law Centre (NI) currently provides an “encyclopaedia of rights" and they also host a range of training events. The Equality Commission provides written advice and guidance in the form of a “Model Equal Opportunities Policy" and a “Unified Guide for Employers". The FSB also suggested the need for clear and comprehensive advice that is available through the Internet. A code of practice, rather than regulations, would be beneficial if cases are taken to a formal level.

48. Given that a number of organisations already provide information in various forms, the Committee would agree with the Department that a coordinated inter-agency approach is needed to information provision to ensure that information is accurate and easily accessible and feels that it is necessary to collate all of the appropriate information in a single publication that is readily available to employers and employees in a range of formats and languages. An extension of the current remit of the LRA would allow for this to be provided as a “one stop shop".

49. An enquiry / helpline service would also be extremely beneficial whereby employees and employers could seek professional advice on their rights and responsibilities. The LRA currently provide such a service but it is extremely resource intensive and expensive. There would need to be increased financing and additional staff assigned to the service in order to reduce the high percentage of missed calls that could well result in callers making an uninformed decision as to how to progress. The Law Centre (NI) also provides an advice helpline, aimed primarily at employees, as does the Equality Commission, aimed at employers. The CBI emphasised the good work that the LRA currently carries out through its advice helpline but pointed out the need for the refocusing of resources to ensure that the service can be utilised to its full potential. Again, an extension of the current remit of the LRA would allow for this to be provided as a “one stop shop".

The role of the public sector

50. As Central Government are responsible for the introduction of employment related legislation, the Committee agreed with a number of witnesses that it is imperative that the public sector plays its part in the development and application of best practice models of dispute resolution and should lead by example. This should not be limited to Government Departments but should also extend to agencies and arms-length bodies that come under the public sector umbrella.

51. As mentioned earlier, employers have raised concerns over the complicated laborious process of meeting their obligations under ever-changing employment regulations and the Committee feels that good practice models and guides need to be developed to assist employers in meeting their obligations to employees. In developing such models the Department suggested that an accreditation system could be developed that includes benefits for accredited employers. The Committee welcomes this approach by the Department to develop modular accredited training in ADR and would support the development of such a programme.

52. Concerns were raised about the alleged automatic approach of public authorities and bodies to follow the option of court proceedings rather than attempts at resolution on account of the fact that an employee will run out of time, money and patience. Such an approach places the employee at a disadvantage to the employer. The LRA felt that this was not necessarily their experience and felt that it should be born in mind that public sector organisations vary in their approach to dispute resolution. It has already been said that public sector organisations should lead be example and a consistent approach, based on best practice, across all organisations would be welcomed. NIC-ICTU pointed out that this approach is not limited to the public sector but also extends to the private sector.

53. The CBI pointed out the ever-present awareness of public bodies to the implications of not following procedures and the scrutiny that they may undergo from the Northern Ireland Audit Office (NIAO). NIC-ICTU pointed out that the tribunal is considered to be a means to justify, to the NIAO, the paying out of money.

Conclusions

54. Based on the evidence received, and taking on board the views of Members, the Committee would be in agreement with witnesses that there is a need to develop and promote a culture of early dispute resolution as opposed to seeking legal redress through the tribunal system as the most appropriate approach. Much work will be needed to change this current mindset.

55. The Committee agreed that there is a need to reform the current statutory procedures, but would emphasise the importance of ensuring that the revised system is properly thought through and represents a synergy of the best of the current system with the best of the options for change, to develop a system that meets our needs for resolving workplace disputes while allowing greater access to justice and improved efficiency. The current three-step system should be repealed and a more appropriate system put in place that removes the apparent flaw that leads to earlier formalisation of complaints, as outlined by a number of witnesses. The new system should ensure the protection of the rights of individuals and employers, and their access to justice.

56. The Committee agreed fully with those who gave evidence that ADR should be promoted as the most appropriate alternative to tribunals in order to protect the privacy of those involved and so ensure the pursuit of a faster, flexible and more cost effective means of settling a grievance especially given the current economic climate. It was also agreed that a system should be put in place that identifies the most appropriate method of ADR on a case-by-case basis to ensure the best possible outcome.

57. The Committee saw the benefits, and heard the drawbacks, of implementing a Rights Commissioner system and feels that further investigation and evaluation is needed before such as system might be adopted.

58. The Committee agreed with a number of witnesses who stated that the role of the Labour Relations Agency should be extended to cover a wider range of advice and ADR services and that there is a need for the refocusing of the LRA’s resources in order to provide such extended services.

59. The Committee also agreed with those witnesses who identified the importance of the tribunal system, but also took on board the concerns that employers and employees have around that system.

60. Irrespective of what form the revised system takes, the Committee feels that there is a need to ensure that it makes dispute resolution simpler and less bureaucratic for both employer and employee and that it does not simply replace one set of complex and confusing rules and regulations with another that are not user-friendly.

61. The Committee strongly believes that the provision of more accessible information and the promotion of a clearer understanding of employer and employee rights and obligations by all those involved are key to the success of any revised system. Lack of accurate information and clear instructions for those participating in the current structures was a recurring theme raised by all of those who gave evidence and this is an issue that needs to be addressed in order for the revised system to be meaningful.

62. The Committee is of the opinion that the public sector plays an extremely important role in the process by, firstly, ensuring that it leads the way in developing best practice models and, secondly, by leading by example through implementing these models.

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings Relating to the Report

Wednesday, 12th November 2008

Room 135, Parliament Buildings

Present: Ms Sue Ramsey MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Robin Newton MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Alex Attwood MLA

Mr Paul Butler MLA

Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Mr William Irwin MLA

Ms Anna Lo MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

Mrs Claire McGill MLA

In Attendance: Mr Peter Hall (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Trevor Allen (Assistant Committee Clerk)

Mr Collan Cree (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Richard Keating (Clerical Supervisor)

Ms Jessica Dougan (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Alex Easton MLA

The meeting opened at 10:33am in public session.

2. Departmental briefing on Alternative Dispute Resolution

The Committee received a briefing from Departmental Officials: June Ingram, Director of Strategy and Employment Relations Division, and Tom Evans, Head of Employment Relations Policy & Legislation Branch, on the Department’s review of methods for resolving disputes that arise in the workplace. The briefing was followed by a question and answer session.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 12:27pm.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 19th November 2008

Room 135, Parliament Buildings

Present: Ms Sue Ramsey MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Robin Newton MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Alex Attwood MLA

Mr Paul Butler MLA

Mr Alex Easton MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Ms Anna Lo MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

In Attendance: Mr Peter Hall (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Trevor Allen (Assistant Committee Clerk)

Mr Collan Cree (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Richard Keating (Clerical Supervisor)

Ms Jessica Dougan (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mr William Irwin MLA

Mrs Claire McGill MLA

The meeting opened at 10:32am in public session.

5. Matters Arising

Agreed: The Committee discussed its future work with respect to Alternative Dispute Resolution. Members also noted an initial research paper on this issue from the Assembly Research and Library Services. Members agreed that the Committee Clerk take the issue forward with Assembly Research Services.

Agreed: Members also agreed that representatives of the Departmental steering group be invited to brief the Committee.

Agreed: Members noted correspondence from the Labour Relations Agency, requesting the opportunity to brief the Committee on dispute resolution, and agreed that representatives be invited to brief the Committee on this issue.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 11:55am.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 14th January 2009

Stranmillis University College,

Stranmillis Road, Belfast

Present: Ms Sue Ramsey MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Robin Newton MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Alex Attwood MLA

Mr Paul Butler MLA

Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mr Alex Easton MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Mr William Irwin MLA

Ms Anna Lo MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

Mrs Claire McGill MLA

In Attendance: Mr Peter Hall (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Trevor Allen (Assistant Committee Clerk)

Mr Richard Keating (Clerical Supervisor)

Ms Jessica Dougan (Clerical Officer)

The meeting opened at 10:31am in public session.

2. Briefing from the Labour Relations Agency (LRA) on Workplace Dispute Resolution

The Committee received a briefing from representatives of the Labour Relations Agency (LRA): Jim McCusker, Chairman, Penny Holloway, Director of Conciliation and Arbitration, Roden Ward, Board Member, and Julie Anne Clarke, Board Member, on the Committee’s work on workplace dispute resolution. The briefing was followed by a question and answer session.

3. Briefing from the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) on Workplace Dispute Resolution

The Committee received a briefing from representatives of the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB): John Friel, Regional Manager, Wilfred Mitchell OBE, Chairman of the NI Area Policy Unit, and Carolyn Brown, Policy Manager, on the Committee’s work on workplace dispute resolution. The briefing was followed by a question and answer session.

8. Any Other Business

Members noted a paper from Assembly Research and Library Services in relation to Alternative Dispute Resolution.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 11:59am.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 4th March 2009

Room 135, Parliament Buildings

Present: Ms Sue Ramsey MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Robin Newton MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Alex Attwood MLA

Mr Paul Butler MLA

Mr Alex Easton MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Mr William Irwin MLA

Ms Anna Lo MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

Mrs Claire McGill MLA

In Attendance: Mr Peter Hall (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Trevor Allen (Assistant Committee Clerk)

Mr Richard Keating (Clerical Supervisor)

Ms Jessica Dougan (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

The meeting opened at 10:05am in public session.

3. Briefing from the Law Centre (NI) on Workplace Dispute Resolution

The Committee received a briefing from representatives of the Law Centre (NI): Mark Beal, Policy Officer, Daire Murphy, Employment Advisor, and Caroline Maguire, Employment Advisor, on the Committee’s work on workplace dispute resolution. The briefing was followed by a question and answer session.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 1:02pm.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 18th March 2009

South Eastern Regional College,

Bangor Campus

Present: Ms Sue Ramsey MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Robin Newton MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Alex Attwood MLA

Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mr Alex Easton MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Ms Anna Lo MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

Mrs Claire McGill MLA

In Attendance: Mr Peter Hall (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Trevor Allen (Assistant Committee Clerk)

Mr Richard Keating (Clerical Supervisor)

Ms Jessica Dougan (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Paul Butler MLA

Mr William Irwin MLA

The meeting opened at 10:33am in public session.

4. Review of Workplace Dispute Resolution: Public Consultation

The Committee noted the Department’s draft public consultation document on Workplace Dispute Resolution and Members indicated approval that the draft document be presented to the Executive on 26th March.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 12:27pm.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 25th March 2009

Room 135, Parliament Buildings

Present: Ms Sue Ramsey MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Robin Newton MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Alex Attwood MLA

Mr Paul Butler MLA

Mr Alex Easton MLA

Mr William Irwin MLA

Ms Anna Lo MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

Mrs Claire McGill MLA

In Attendance: Mr Peter Hall (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Trevor Allen (Assistant Committee Clerk)

Mr Richard Keating (Clerical Supervisor)

Ms Jessica Dougan (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

The meeting opened at 10:05am in public session.

3. Briefing from the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) on Workplace Dispute Resolution

The Committee received a briefing from Deirdre Stewart, Assistant Director of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), on the Committee’s work on workplace dispute resolution. The briefing was followed by a question and answer session.

8. Briefing from the Equality Commission on Workplace Dispute Resolution

The Committee received a briefing from representatives of the Equality Commission: Bob Collins, Chief Commissioner, and Eileen Lavery, Head of Strategic Enforcement, on the Committee’s work on workplace dispute resolution. The briefing was followed by a question and answer session.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 12:37pm.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 29th April 2009

Room 135, Parliament Buildings

Present: Ms Sue Ramsey MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Alex Attwood MLA

Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mr Alex Easton MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

Mrs Claire McGill MLA

In Attendance: Mr Peter Hall (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Trevor Allen (Assistant Committee Clerk)

Mr Andy Cooper (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Richard Keating (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Bill Kinnear (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Robin Newton MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Paul Butler MLA

Mr William Irwin MLA

Ms Anna Lo MLA

The meeting opened at 10:10am in public session

6. Briefing from the Northern Ireland Committee, Irish Congress of Trade Unions (NIC-ICTU) on Workplace Dispute Resolution

The Committee received a briefing from representatives of the Northern Ireland Committee, Irish Congress of Trade Unions (NIC-ICTU): Peter Bunting, Assistant General Secretary, and Eugene McGlone, Deputy Regional Secretary of UNITE Union, on Workplace Dispute Resolution. The briefing was followed by a question and answer session.

Agreed: Members agreed that the Committee should meet with the Republic of Ireland’s Rights Commissioner.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 11:27am.

[EXTRACT]

Wednesday, 24th June 2009

Room 135, Parliament Buildings

Present: Ms Sue Ramsey MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Alex Attwood MLA

Mr Paul Butler MLA

Ms Anna Lo MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

In Attendance: Mr Peter Hall (Assembly Clerk)

Mr Trevor Allen (Assistant Committee Clerk)

Mr Andy Cooper (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Bill Kinnear (Clerical Officer)

Apologies: Mr Robin Newton MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Rev Dr Robert Coulter MLA

Mr Alex Easton MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Mr William Irwin MLA

Mrs Claire McGill MLA

The meeting opened at 10.13am in public session

4. Consideration of Draft Committee Response on Workplace Dispute Resolution

Agreed: The Committee considered and agreed, subject to amendment, its Report on the Review of Workplace Dispute Resolution.

The Committee ordered that the report be printed.

The Chairperson adjourned the meeting at 12:27pm.

[EXTRACT]

Appendix 2

Minutes of Evidence

12 November 2008

Members present for all or part of the proceedings:

Ms Sue Ramsey (Chairperson)

Mr Robin Newton (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Alex Attwood

Mr Paul Butler

Rev Dr Robert Coulter

Mr David Hilditch

Mr William Irwin

Ms Anna Lo

Mr David McClarty

Mrs Claire McGill

Witnesses:

Mrs June Ingram, Department for Employment and Learning

Mr Tom Evans, Department for Employment and Learning

1. The Chairperson (Ms S Ramsey): In this session, departmental officials will outline the background to dispute resolution. Members should be aware that the Department has released a pre-consultation paper to key stakeholders. Hansard will record the session because the Committee may decide to examine the issue in greater detail and, perhaps, conduct an inquiry or produce a report. Members must ensure that all mobile phones are switched off. I thank the officials for attending and providing a paper.

2. Mrs June Ingram (Department for Employment and Learning): I thank the Committee for the opportunity to detail the current state of play and the Department’s proposals for progress on its alternative dispute resolution (ADR) review. Tom Evans will explain the process that is under way and illustrate the range and depth of the policy-development process. We have examined developments in GB, and we are considering which package is appropriate for Northern Ireland, which has its own structures, employment-relations culture and economic landscape.

3. The role of improved workplace relations in economic development is to help productivity, to reduce costs and to resolve disputes earlier, and our ideas are set within that economic context. Tom is chairman of the steering group for the consultation process.

4. Mr Tom Evans (Department for Employment and Learning): I thank the Committee for inviting us. As the Chairperson mentioned, we provided a background paper. Furthermore, we provided a copy of our slides, and if the Committee is content, I intend to make a short presentation, which will last approximately 20 minutes, to outline the background, the current position and our vision for the future. I am happy to stop at any stage if members have any burning questions.

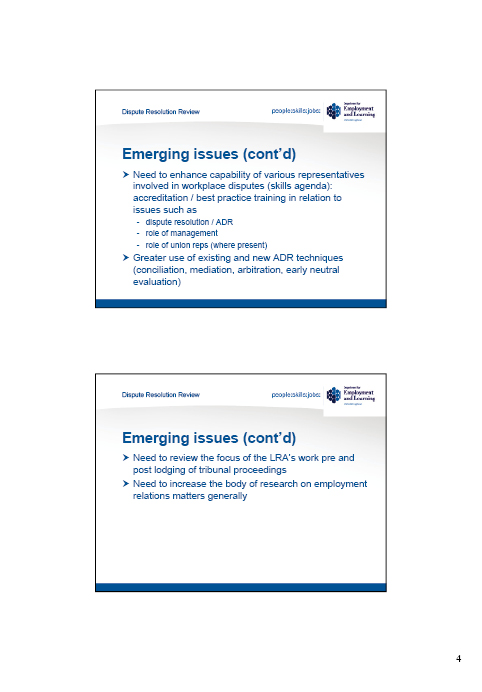

5. The Committee has several papers on the subject, and, therefore, I will outline some background information rather than give too much detail. I will discuss the pre-consultation process, and although there are no fixed views as yet, we are keen to share with the Committee the emerging issues arsing from that process. I will discuss the potential change agenda and some of the implementation projects that could arise from a public consultation in 2009.

6. The current statutory procedures were introduced in GB in 2004 and in Northern Ireland in 2005. When I took up my job, GB had already taken the decision to change the 2004 GB procedures before the ink had even dried on the Royal Assent document. Michael Gibbons was asked to conduct a review, which commenced at the end of 2006 and continued into 2007. The brief seemed to focus on a repeal of the statutory procedures. Thereafter, Gibbons recommended a repeal of the statutory procedures, and an Employment Bill, containing seven clauses — one of which will repeal the statutory procedures — is progressing through Westminster.

7. The Gibbons review did not cover Northern Ireland, which is why the Department took the decision to go through a more extensive pre-consultation process. As June said, it is a major policy, which covers every employer/employee relationship in Northern Ireland. Therefore, it is a macro policy, rather than a niche policy. The Department decided that it would go through a pre-consultation exercise, and, as the Chairperson said, members received the report on that. It covered the ground that the Gibbons review covered, and it ensured that the Northern Ireland system had an opportunity to comment.

8. The Department took a long time to go through the pre-consultation process, but it is probably better to take a measured approach and get a proper feel from the community. We went through the pre-consultation process from February to April 2008. The Minister established a consultation steering group, which is a different process, and it is made up of the Northern Ireland Committee of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions, the Federation of Small Businesses, the Confederation of British Industry, the Equality Commission, and the Labour Relations Agency, as the main deliverer of conciliation and alternative dispute resolution techniques and processes.

9. The steering group has met approximately six times, and its role is to oversee the consultation process and to bring to the Minister — probably in the next month or so — a consultation document that will form the basis of a public consultation. The group has received presentations from a range of experts, including officials from our counterparts, the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform. I frequently get that title wrong — it was formerly known as the DTI, and it was always easier to say. The officials talked about developments and about how the process was moving forward.

10. The steering group also received a presentation from the Labour Relations Commission in the Republic of Ireland. It was represented by the chief executive who was accompanied by a rights commissioner, as a rights commissioner system operates in the South of Ireland. We also had a presentation from Professor Paul Teague from the school of management in Queen’s University. Paul is well regarded for his work on international models of best practice in employment conflict resolution. I am being careful to put the word “employment" in front of the words “conflict resolution". We also had a fine presentation from the Labour Relations Agency on best practice, as there is no need to reinvent the wheel.

11. We met with a range of key stakeholders. We issued a consultation to the usual suspects — the consultation stakeholders — but we conducted face-to-face meetings with every stakeholder who wished to meet us. In fact, we were proactive in encouraging them to meet with us.

12. We also established user panels, because this is very much a practice issue. There is a lot of anecdotal evidence to suggest that some procedures are working and some are not. Therefore, we established user panels, which were made up of representatives of the voluntary sector and the trade unions, as well as employment lawyers and HR professionals. That proved to be hugely beneficial. The Law Centre, which supports unrepresented employees who do not have a union and do not have the wherewithal, brought together a range of people from citizens advice offices around Northern Ireland and from other support and voluntary agencies. We ran a half-day workshop to examine the issues for people who support employees who have difficulties in the workplace.

13. We also had meetings with representatives from all the trade unions in Northern Ireland. We met with barristers and employment lawyers to find out their views, and that was a very useful exercise. They did not concentrate on their business, which is when cases get to the tribunal stage, but rather they considered the type of issues that would help to resolve disputes. They see the disputes at the other end, but, in fairness, they took their commercial hats off at that stage.

14. I am meeting with a range of HR professionals from the larger employers — that is, the public and private sector. Through contacts with the Labour Relations Agency, we tapped into some small employers, and into consultants who deal exclusively with small employers. That was a useful exercise, as they understand the pressures and struggle in delivering the employment law regulations.

15. We have audited existing good practice and have looked at international best practice. We have an ongoing research project that involves face-to-face interviews with 40 people who were claimants in an industrial tribunal or a fair employment case and representatives of 40 employers. It has been quite difficult to source people who are willing to participate — often, people who have been through a tribunal or case are not that happy to participate. Another problem is that people’s decision to participate can be influenced by the outcome of a tribunal. However, we are hoping to populate the consultation document with feedback from that research project.

16. June and I made a presentation to our departmental board, because it was important to ensure that the board understood the emerging issues and that we were not getting ahead of ourselves in relation to departmental objectives. There are statutory procedures, which can be retained, repealed in part or repealed in full. However, that will not be enough. There must be a cultural change in the way that employment relations are arranged in Northern Ireland; that is, the way that employees raise their grievances and how employers deal with those. That issue came out of the pre-consultation process very clearly.

17. There is an issue regarding whether there should be a rights-based system that recognises the position of employees and gives them ready access to the justice system or a system that focuses on promoting good employment relations. The steering group, which represents both employees and employers, has acted very corporately. That group believes that such systems are not mutually exclusive. There can be a system that allows people access to justice — whether that is justice in their own employment environment or recourse to an industrial or a fair employment tribunal — with work also being done to strengthen employment relations in Northern Ireland so that fewer disputes happen and, when they do, more are dealt with informally.

18. We are finding that employers in small businesses have a problem with employment regulations. In a small business, the employer is often the person who sweeps the floor, who registers with Companies House and who does all the other things, and they struggle with what they see as a range of very complicated procedures. The pre-consultation showed that there is a feeling that small businesses should not be exempt from their responsibilities under legislation, but that models of good practice should be available to help them to deliver on those responsibilities.

19. There is a question mark over the role of the public sector. The pre-consultation indicated that people felt that if central Government are introducing legislation, the public sector should try to have best practice. The departmental board has agreed that we should consider having a pilot scheme in our Department, which involves using softer techniques that are outside of the procedures. We are also going to try to run that pilot scheme in one or two public- and private-sector organisations.

20. A need remains for mechanisms that encourage early resolution of disputes. It is possible to take either the carrot or the stick approach — the pre-consultation has shown that people are in favour of having elements of both. Mechanisms for employers could include best-practice models, kite marking, and an accreditation system that includes benefits for accredited employers. Using the stick approach, if employers are not following sensible good practice and are not discharging their responsibilities to employees, the tribunal system can be used, with measures being taken dependent on the outcome of that.

21. When I started in this job, a very simple thing that I did was to visit the websites of a range of organisations. What does an employee with a dispute do? Good information has been produced by the Labour Relations Agency, Directgov, Citizens Advice, and the Department for Employment and Learning (DEL). All those publications are professional and accurate, but employees who are looking for information will tend to tap into one website, then into another, and will find themselves wondering which is correct.

22. The pre-consultation has shown that people agree that it may be helpful to have an inter-agency approach to information provision. That would involve providing one piece of information for employers that is a sign-posting document, with the logos of all the relevant organisations on it. Perhaps it could be launched at a nice event with the Minister and the Committee. That would seem to be a quick and easy way to assist people.

23. There is a need to change the culture in Northern Ireland by implementing good employment relations that will mean happy employers and fewer disputes. Disputes should be resolved early. The capabilities of managers, HR specialists, union reps and other people who are involved should be enhanced so that they are able to support employees and employers and resolve disputes. Professor Paul Teague from Queen’s University mentioned that as well. The Department for Employment and Learning is keen on that, because we have a skills agenda, and we are interested in developing some pilot arrangements.

24. Queen’s University is working with University College Dublin and the Irish Business and Employers Confederation to develop a Masters qualification in conflict resolution in an employment environment. Professor Paul Teague said that it could be adapted to develop an accredited modular approach. It would not be for the HR function only; in large organisations, it would be good personal development for middle managers. Those are the people who deal often with grievances as they arise. Sometimes by not handling those issues well, they escalate, and that is where the problems arise and parties divide. The important issue is the skills agenda and the early resolution of problems.

25. The Labour Relations Agency is the main deliverer of conciliation and alternative dispute-resolution processes, and it does a fine job. It uses conciliation, mediation and arbitration techniques. There are other mechanisms, such as early neutral evaluation. The question is: are we getting the right numbers? Arbitration is not used often, but it is more informal than the tribunal system.

26. The voluntary organisations informed us that they are aware of people who were nervous of the system and who did not have much money. The thought of going to a tribunal made some of those people withdraw their cases. However, they would have been more attracted by an independent, less legalistic process in which there was not any cross-examination. The lawyers said the same thing. Trade union colleagues wondered why we were consulting with the lawyers — ambulance chasing springs to mind — but the lawyers were professional, and we are keen to meet with them again.

27. There may be a need to review the focus of the Labour Relations Agency pre- and post-lodging of tribunal proceedings. There is a perception that the Labour Relations Agency deals with cases at tribunal stage, because there is an automatic default that the agency becomes involved when proceedings are lodged. Perhaps people are not aware that the Labour Relations Agency does a lot of good work pre-lodging of proceedings, and it needs to be promoted.

28. There is a paucity of research in employment relations in Northern Ireland. We get documents from GB — and that is fine — but Northern Ireland is different from other regions in the UK. Our economy is structured differently, and we have a higher dependency on public-sector jobs and small employers. That is coming out strongly. There is also a need to evaluate the effectiveness of the Office of Industrial Tribunals and the Fair Employment Tribunal and to link it with the work of the Labour Relations Agency. That is not to say that there is not evaluation, but it needs to be more structured, and it must capture the views of the various parties involved in a dispute as they go through the process.

29. The president of the Office of Industrial Tribunals and the Fair Employment Tribunal shared with us an evaluation of three non-industrial tribunals in Great Britain. We were informed of the research methodologies that are applied there, and that was helpful.

30. There is a need to review the rules and procedures in the tribunal system. My colleague Alan Scott was involved in developments over 2004 and 2005. Please do not ask me any questions about that, because it is a mystery to me. However, I will know more about it before we get to the end of the review.

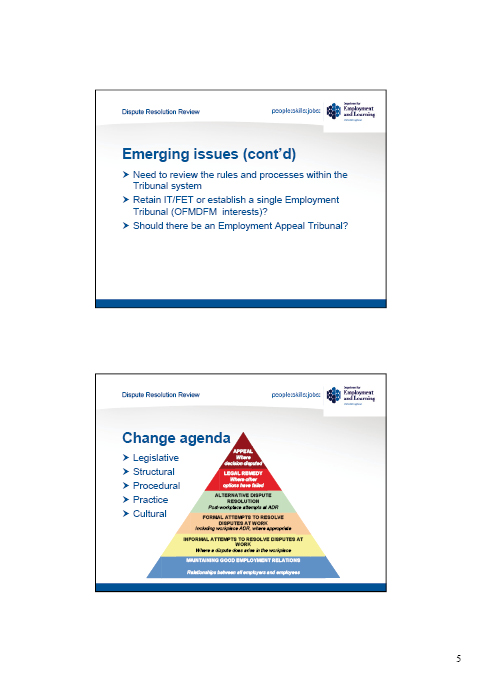

31. There is a question of whether there is a need for a fair employment tribunal and an industrial tribunal, or whether one would be sufficient. Those questions must be asked. Through their work on a single equality Bill, the First Minister and the deputy First Minister have an interest in that issue. Any appeals to an industrial tribunal or a fair employment tribunal must go to the High Court. There is an employment appeals tribunal in England; the question is whether there should be an employment appeals tribunal in Northern Ireland. The steering group and others have said that a decision on whether to bolt on an extra layer must be based on knowledge of what the whole system will comprise.

32. We drew a pyramid to attempt to explain the change-agenda process. The contracts of employment of everyone in Northern Ireland are represented at the bottom of the pyramid. We want the consultation document to include questions on what needs to be done to strengthen employment relations. I have mentioned best-practice models and the need to enhance capability through the skills agenda. The ability of managers and union representatives is of key importance to the informal issues and mechanisms that can help with disputes.

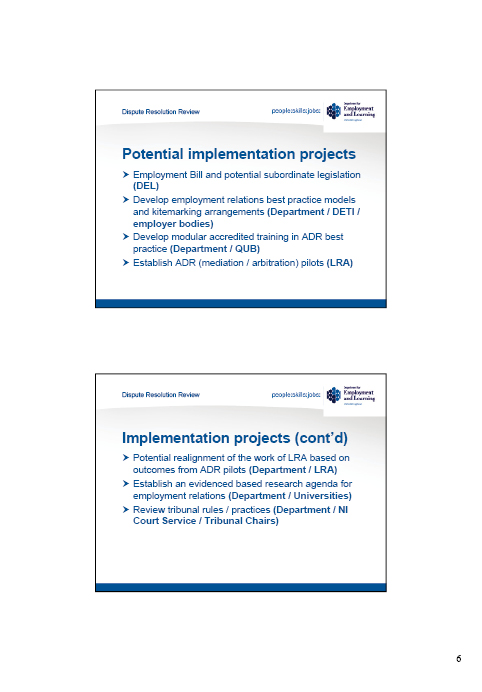

33. Consideration must be given to how alternative dispute resolution can be used when a dispute becomes formal. In the public sector, little use is made of ADR, which is why pilot schemes are being considered. Great procedures are in place, but flesh must be put on their bones. When the employment relationship has broken down, organisations such as the Labour Relations Agency are used. Other private organisations are now using trained professional mediators in such a process, and the consultation will ask questions about that. Questions must also be asked on how a legal remedy can improve the appeal process.

34. Several implementation projects may arise from the review. I stress that those are only potential projects and that a public consultation would be required for those. We are keen to hear the Committee’s views. Any changes to the statutory procedures would require an employment Bill to come to the Assembly; no changes can be made without the Assembly’s approval. Primary legislation would be used to provide the enabling powers for a new mechanism, and the subordinate legislation would provide the flexibility to make changes, especially as one evaluates what works and what does not work.

35. The potential development of best-practice models for employment relations and the potential to introduce kite-marking arrangements could happen among the Department for Employment and Learning, the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment and the employer lead bodies. DEL has an explicit remit in the change agenda to develop modular-accredited training in alternative dispute resolution, and we are keen to work with Queen’s University and other bodies. The list of organisations with which we might work is not intended to be exhaustive; it is intended to provide a feel for the kinds of people who may be involved.

36. Following the Gibbons review, several pilot projects have been run in GB. It is sensible, therefore, to consider pilot projects in mediation and arbitration in order to find out whether that approach works well and to evaluate it. It is important to test the system.

37. Potentially, the work of the Labour Relations Agency, which is funded by DEL, may be realigned. That will depend on the outcome of the public consultation, the direction of the policy and the results of the pilot projects. As the spending Department, DEL will influence the way in which the Labour Relations Agency does its work. An evidence-based research agenda is needed, and a review of the tribunal rules must also be considered.

38. The Department has produced some indicative timescales for the way forward. We hope to produce a consultation document by the end of December 2008. Although the Minister does not regard that document as his Christmas present to the Committee, we will share it with members. After that, the document will be subject to ministerial and Executive approval, and in February 2009, it will go out for a 12-week public consultation. The Department hopes to produce its response to the public consultation document and to produce policy proposals before the summer. Those are only indicative timescales, and the Committee may want to get involved in those. Our presentation also asks the Committee how it wants to be involved.

39. The Chairperson: Thank you, Tom. I now ask members to indicate whether they want to ask questions or make a comment, because today’s agenda contains a number of items and I want to keep the Committee running close to the anticipated timings. Robin and Alex have indicated that they wish to speak.

40. The Committee has been involved in a number of issues over the past few months. During the presentation, I thought about the further education lecturers’ pay dispute. If that method of dispute resolution came into being, would that resolve that pay dispute? We are being told that the British Treasury is responsible for the resolution of that dispute. The Minister, the further education lecturers and the colleges want the dispute, which is ongoing, to be resolved.

41. Mrs Ingram: The further education lecturers’ dispute is operating under the current procedures. We want to consider whether the procedures could be improved to help to resolve disputes. I am not sure whether we would be able to resolve the further education dispute, but we can learn from what has happened.

42. Mr Evans: If a dispute is over money — about what people believe that they are entitled to and when pay negotiations are needed — the procedures will not resolve it. However, they will improve the process of negotiation around that dispute. They will recommend that those negotiations happen earlier; that early warning systems are established; and that the employer side and the employee side are more reactive and responsive, and move to proper dialogue at an earlier stage. Employment relations and dispute resolutions are about early interventions through professional support.

43. The Chairperson: I appreciate that, but I am conscious that we could be talking about nursing staff or further education lecturers. Many disputes that we face — or will soon face — are about pay. If the issue is out of our hands, where does it sit? That needs to be considered during the consultation.

44. Mrs Ingram: That is a very good point.

45. Mr Evans: The statistics indicate that several of those disputes involve tribunals. Some of those are collective disputes about pay or terms and conditions, and the Labour Relations Agency deals with those through its collective-conciliation processes. The problem is that there is a critical mass of individual disputes that must be dealt with. Those have resulted in serious operational costs.

46. The Chairperson: I do not want to sound negative, because this is something in which the Committee wants to be involved and we mentioned that a few months ago. However, if we are reaching for the stars, we should reach for them all. There is no point in dealing with the smaller issues if the bigger issues will come and bite us.

47. You talked about the emerging issues and the need for an inter-agency approach to the provision of information. I assume that that information will be available in various languages, so that the maximum amount of people can access it. I have no doubt that there are many positive, proactive small businesses out there. It might not necessarily be their fault if they do not know about an issue before it becomes a dispute in the workplace. We need to be proactive and ensure that those small businesses get that information.

48. Last week in the Chamber, I raised the point that some people do not know their rights, and some business are not aware of those either. If changes are being made to the laws, we need to be careful that — rather than it becoming an issue — we provide people with a lot of information, because the difficulties are not caused by people misbehaving. The example of paternity leave regulations struck me when you were talking about that issue.

49. Mr Evans: That is very helpful; because some very sensible measures could be taken that do not require major changes. If 100 people on the street were asked what the Labour Relations Agency is, they would not know. There needs to be a proactive approach to the provision of guidance and information.

50. Mr Newton: This is a very timely and interesting piece of work. The Department may be aware that the Assembly has debated red tape and bureaucracy — particularly around small firms — and employment law and dispute resolutions fall into that.

51. I note the wise comment about the need to look to a bespoke solution that better reflects the structures of the local economy. If those are the driving thoughts, it is very good. At the end of the day, we cannot disadvantage either the employer or the employee. However, to follow the point that the Chairperson raised, if it is a major dispute — a college lecturers’ dispute — and if we decide that this is the way to go, will that fall within this remit, or will it be devoted only to the small and medium-sized enterprises in the economy?

52. Mr Evans: This refers to every dispute in Northern Ireland, whether involving a collective, an individual, a small employer, a large employer, or an employee. It covers everything. There may be a need to consider a model for collective conciliation, and how dispute resolution and the appropriate agencies can work together.

53. Mr Attwood: I agree with Robin that the discussion is timely and useful. I am very protective of the equality and employment architecture in the North. If it had not been for strong laws and strong enforcement over several decades, we would not have moved as quickly as we have — although not quickly enough — to the more equal society that we now have. For that reason, I would be cautious about going down the road of merging the Fair Employment Tribunal and the Industrial Tribunal. It is a fair and proper question to ask, but we are not yet in the situation where we can make the wider political and policy statement that would be inherent in answering that question positively.