Review into the Impact and Value of Museums in Northern Ireland

Session: 2010/2011

Date: 10 March 2011

Reference: 38/10/11R

Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure

Review into the

Impact and Value of Museums

in Northern Ireland

Together with the Minutes of Proceedings of the Committee

Relating to the report, Minutes of Evidence and Written Submissions

Ordered by The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure to be printed 10 March 2011

Report: NIA 38/10/11R The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure

Session 2010/2011

Fifth Report

Powers and Membership

Powers

The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure is a statutory departmental committee established in accordance with paragraphs 8 and 9 of the Belfast Agreement, Section 29 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and under Assembly Standing Order 48. The Committee has a scrutiny, policy development and consultation role with respect to the Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure and has a role in the initiation, consideration and development of legislation.

The Committee has the power to:

- Consider and advise on departmental budgets and annual plans in the context of the overall budget allocation;

- Approve relevant secondary legislation and take the committee stage of the primary legislation;

- Call for persons and papers;

- Initiate inquires and make reports; and

- Consider and advise on matters brought to the Committee by the Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure.

Membership

The Committee has 11 members, including a Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson, with a quorum of 5 members.

The membership of the Committee since 9 May 2007 has been as follows:

Mr Barry McElduff (Chairperson)

Mr Declan O’Loan (Deputy Chairperson) c, g

Lord Browne of Belmont

Mr Thomas Burns g

Mr David Hilditch d

Mr William Humphrey e

Mr Kieran McCarthy

Mr Billy Leonard f

Mr David McClarty h

Mr Ken Robinson a

Mr Pat Sheehan b

a Mr Ken Robinson replaced Mr David Burnside with effect from 18 June 2007

b Mr Pat Sheehan replaced Mr Raymond McCartney with effect from 13 December 2010. Mr Raymond McCartney replaced Mr Paul Maskey with effect from 10 March 2008

c Mr PJ Bradley replaced Mr Pat Ramsey with effect from 29 June 2009

d Mr David Hilditch replaced Mr Trevor Clarke with effect from 13 September 2010. Mr Trevor Clarke replaced Mr Jim Shannon with effect from 15 September 2009

e Mr William Humphrey replaced Ms Michelle McIlveen with effect from 4 October 2010. Ms Michelle McIlveen replaced Mr Nelson McCausland with effect from 15 September 2009

f Mr Billy Leonard replaced Mr Francie Brolly with effect from 7 January 2010

g Mr David McNarry ceased to be the Deputy Chairperson and Member of the Committee with effect from 12 April 2010. Mr Declan O’Loan was appointed Deputy Chairperson with effect from 13 April 2010. Mr P J Bradley replaced Mr Declan O’Loan as Deputy Chairperson with effect from 28 May 2010. Mr Declan O’Loan replaced Mr P J Bradley as Deputy Chairperson with effect from 28 June 2010

h Mr David McClarty was appointed as a Member with effect from 13 April 2010. Mr Dominic Bradley ceased to be a Member with effect from 13 April 2010

Table of Contents

Report

1. Assessing the impact and value of museums in Northern Ireland

2. Work conducted so far to monitor the social and economic value of Museums in Northern Ireland

3. Understanding economic and social impact

5. Areas of good practice within the museum sector outside of Northern Ireland

Appendices

Written Submissions to the Committee

List of Abbreviations used in the Review

ACM - Armagh County Museum

AIM - Association of Independent Museums

ALMA-UK - Archive, Libraries and Museum Alliance

AVE - Advertising Value Equivalency

BBC NI - British Broadcasting Corporation Northern Ireland

C4 - Channel 4

CASE - Cultural and Sport Evidence Programme

CEDAR - Centre for Environmental Data and Recording

CHP - County Heritage Plan

CSI - Cohesion, Sharing and Integration

CSR - Comprehensive Spending Review

CyMAL - Museums Archives and Libraries Wales

DCAL - Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

DCMS - Department for Culture, Media and Sport

DETI - Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

DFP - Department of Finance and Personnel

DRD - Department for Regional Development

EFTEC - Economics for the Environment Consultancy

GB - Great Britain

GLO - Generic Learning Outcomes

GMTV - Good Morning Television

GVA - Gross Value Added

HLF - Heritage Lottery Fund

ILFA - Inspiring Learning For All

KPI - Key Performance Indicator

MAGNI - Museums and Galleries of Northern Ireland

MGS - Museums Galleries Scotland

MLA - Museums Libraries Archives

NI - Northern Ireland

NIMC - Northern Ireland Museums Council

NISRA - Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency

NITB - Northern Ireland Tourist Board

NMNI - National Museums Northern Ireland

OFMDFM - Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister

PRONI - Public Records Office Northern Ireland

PSA - Public Service Agreements

PWC - PricewaterhouseCoopers

ROI - Republic of Ireland

RPA - Risk Potential Assessments

RTÉ - Raidió Teilifís Éireann

SCA - Scottish Council on Archives

SLIC - Scottish Library and Information Council

SROI - Social Return on Investment

STEM - Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths

TDS - Tourism Development Scheme

TSNI - Tourism Strategy for Northern Ireland

TWM - Tyne & Wear Museums

UAFP - Ulster American Folk Park

UFTM - Ulster Folk and Transport Museum

UK - United Kingdom

UM - Ulster Museum

UTV - Ulster Television

VALCAL - Value of Culture, Arts and Leisure

WAG - Welsh Assembly Government

WTA - Willingness to Accept

WTP - Willingness to Pay

Executive Summary

Purpose of the Review

In 2008 the Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure, commissioned a report into the ‘Development of a Museums Policy for Northern Ireland.’ The purpose of this review is to provide a supplementary report to augment the findings of the Committee’s 2008 report focusing, in particular on the economic and social impact and value of museums in Northern Ireland.

Main Findings

The sector makes a contribution of more than £16m to the economy in Northern Ireland, provides employment for many hundreds of people and purchases services from local businesses, including small craft businesses. It provides wider economic and social benefits including cultural tourism, education and life-long learning.

The Committee came to the conclusion that the Executive should acknowledge that the museum and heritage sector is an important industry in Northern Ireland with the potential to assist economic growth.

The Committee concluded that the potential of the museum sector had been underestimated due to the lack of data to make the case. It found research on the sector was out of date and was in urgent need of updating. The Committee agreed that the sector needed to establish a consistent methodology by which to measure and demonstrate the direct and indirect economic and social value of museums, and that partnership working across the museum sector and departments was essential to fully realise the wider economic and social impact and value of museums.

List of Recommendations

1. We recommend that the Executive acknowledges that the museum and heritage sector is an important industry in Northern Ireland with the potential to assist economic growth.

2. We recommend that the research infrastructure is urgently updated and that DCAL issues guidance regarding a more frequent evaluation framework.

3. We recommend that all the museums, libraries and archives in Northern Ireland must establish a consistent methodology by which to measure and demonstrate the direct and indirect economic and social value of Museums, including commonly-agreed standards for data collection. This should include indirect employment, goods and services and associated goods.

4. We recommend that any intelligence gathering (such as the types of information to be gathered and the methodology), should emerge as part of the key actions flowing from the museums policy.

5. We recommend that DCAL provides sufficient resources, in terms of expertise, staff and financial resources to support the museum sector’s ability to collect on a consistent basis, robust data across the local museum sector.

6. We recommend that the ‘Inspiring Learning for All’ framework, which is widely used in museums, libraries and archives in the United Kingdom is further adapted and applied to the museum sector in Northern Ireland.

7. We recommend that research is conducted into the economic value of volunteering in the museums sector in Northern Ireland and is carried out jointly by NIMC and NMNI, which supports the development of a volunteering policy.

8. We recommend that DCAL consider the development of an economic toolkit, using a similar methodology as that used by the Association of Independent Museums, as part of its planned economic and social research programme.

9. We recommend that the lack of research regarding the social benefits of museums on a consistent basis is addressed in DCAL’s economic and social research programme, and that a social evaluation tool is developed in consultation with the museums sector.

10. We recommend that the Department, local authorities and the museum sector use independent research on the impact and value of museums carried out by academics and experts to avoid duplication and additional costs.

11. We recommend that more research is carried out into the cultural value and impact of museums resulting in an effective evaluation tool being developed which can ultimately incorporate the economic, social and cultural impacts of the museum sector.

12. We recommend that DCAL’s new PSAs include targets to measure the contribution of the STEM subjects to the museum sector.

13. In light of budgetary constraints of the 2011-2015 period, we recommend that the Executive commit to examining, across departments the economic and social value of museums with evidence considered, and programmes designed, that fully maximise the social and economic contribution of the museum sector to the economy.

14. We recommend that the museum sector in Northern Ireland continues to be represented by the NIMC on the ALMA project and that the specific research needs of the museum sector, and any pilot projects which may be undertaken, are given adequate support through the course of the project.

15. We recommend that the Department identify examples of good practice in measuring the economic and social impact of museums, and applies this to improving the assessment of the social and economic value and impact of museums in Northern Ireland.

16. We recommend that the incoming Committee request a response to the report from the incoming Minister for Culture, Arts and Leisure in the new Mandate (2011-2015).

Introduction

Review’s Terms of Reference

1. The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure agreed to conduct a focused review on the value and impact of museums in Northern Ireland at the meetings held on 25 November 2010 and 2 December 2010. The terms of reference for the review were agreed at the Committee meeting on 9 December 2010.

Terms of Reference for the Review

2. The Committee sought to provide a supplementary report which would build on the recommendations of the Committee’s 2008/9 ‘Inquiry into the Development of a Museums Policy for Northern Ireland’. The purpose of the review was to assess and analyse how museums bodies monitor and measure the economic and social impact of museums and how the potential of museums in economic terms can be maximised in the era of budgetary cuts and economic instability.

3. Within that framework the Committee sought to:

1 To investigate what work is currently being conducted to monitor the social and economic value of museums in Northern Ireland.

2 To assess what level of understanding exists within the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure and the key museums bodies about the methods of measuring value and impact on a consistent, ongoing basis.

3 To investigate how information about the social and economic impact of museums could be used to assess value for money across government.

4 To seek areas of good practice within the museum sector outside of Northern Ireland, such as those followed by CyMAL, the Heritage Council of Ireland and elsewhere, and make recommendations to the Assembly.

The Review Process

4. The Committee made the decision to hold a short and focused review on the value and impact of Museums in Northern Ireland in December 2010. The Committee agreed to write to key stakeholders, to request submissions on each of the matters included within the terms of reference. Written submissions can be found at Appendix 3.

5. The Committee received 13 submissions and considered oral evidence from 5 key stakeholders, including the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure. Transcripts of the oral evidence sessions are attached at Appendix 2.

6. The Committee also commissioned 2 research papers on the impact and value of museums.

- The first paper entitled ‘Value and impact of Museums: Background information’ provided an overview of the main issues in relation to the review.

- The second paper entitled ‘Assessing the value and impact of Museums’ summarised recent attempts to assess the economic and social impacts of museums across the UK and Ireland and considered the methodologies adopted by such assessments.

7. Copies of these papers are included in Appendix 4.

8. The Committee considered its draft report on 3, 9 and 10 March 2011. The Committee agreed its final report and ordered that the report be printed.

Acknowledgements

9. The Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure would like to express and record its appreciation and thanks to all the organisations and individuals who contributed to the review.

Chapter 1 - Assessing the Impact and Value of Museums in Northern Ireland

10. The review found that the sector makes a contribution of more than £16m to the economy in Northern Ireland, provides employment for many hundreds of people and purchases services from local businesses, including small craft businesses[1]. 968 people are employed directly in the museum sector of which 661 are paid employees and 307 are volunteers[2]. While museums benefit from indirect employment, there would appear to be no sector wide studies of indirect employment in Northern Ireland.

11. The Committee was informed that visitor numbers in 2009/10 to National Museums in Northern Ireland (NMNI) were in excess of 845,000. NMNI anticipate that this will reach 1,000,000 in 2011.

12. The NMNI stated that museums make positive social and economic impacts and are a critical part of the infrastructure of the region[3]. This was a view that was shared by DCAL, the museum sector, academics and funders during the course of the review.

13. During the review, it became clear, that while it was difficult to quantify the social and intrinsic benefits of museums, it was widely accepted that museums have a broader value to society.

14. Social and economic benefits were identified in the following areas:

- Cultural tourism.

- Supporting and enriching formal education.

- Informal lifelong learning.

- Supporting the knowledge/creative economy.

- Providing an environment in which to explore a greater understanding of and respect of culture, history and heritage.

- Contributing to a positive international image of Northern Ireland.

- Well-being and health.

Cultural Tourism

15. The importance of the museum sector to tourism was highlighted across the board by key stakeholders. During evidence, DCAL provided the following statistics on the museum sector:

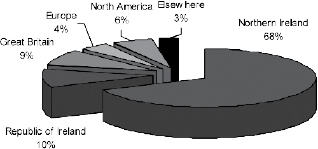

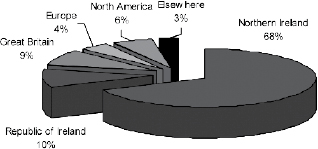

They are a key driver of the Northern Ireland economy; 10% of all visitors to Northern Ireland visit a museum, and 28 % of museum visitors are from out of state. Northern Ireland welcome in excess of 1.5 million visitors each year and nearly 1,000 people work across sector....NMNI runs four of the top of 10 visitor attractions in Northern Ireland.

16. The Northern Ireland Tourist Board provided statistics that supported the important role museums play in supporting tourism:

The 2009 Visitor Attraction Survey estimated that in total there were around 990,000 visits to museums/art galleries in 2009 by Northern Ireland residents and visitors, both on overnight trips and day trips to Northern Ireland. It is estimated that 28% (or around 277,000) were made by those from outside of Northern Ireland (i.e. non-NI residents). These figures give a measure of the part museums play as part of the Northern Ireland visitor experience.

17. According to the Northern Ireland Passenger survey, cultural tourism figures reached 219,500 visitors in 2009.

18. The Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) emphasised the importance of heritage to the economy. During oral evidence, HLF referred to a recent report, entitled ‘Investing in Success,’ which demonstrates that the heritage sector is an integral part of the economy and gives a big boost to tourism. The report states that the heritage sector is the fifth largest industry in the UK. It is ...a crucially important part not just of the £114billion visitor economy...but of our local, regional and national economies as well[4].

Supporting and enriching learning and education

19. During oral evidence, DCAL referred to the contribution of the museum sector to lifelong learning. This assertion was supported across the board and examples were provided of the contribution that the museums sector makes to the educational curriculum and life-long learning:

The sector makes a contribution to education and lifelong learning. Museums enhance delivery of the curriculum by providing inspirational learning experiences. Last year, for example, NMNI along had over 100,000 people in educational programmes[5].

Supporting the knowledge economy and creative industries sector

20. Contributors provided evidence to demonstrate the value of the museums sector to the creative industries. The Northern Ireland Museums Council stated that museums are a fundamental resource for the creative industries and DCAL referred to the importance of the creative sector in attracting people to live in an environment ...that are good at attracting high-value-added creative industries.[6]

21. Providing an environment in which to explore a greater understanding of and respect of culture, history and heritage

DCAL stated that museums are an important aspect of a shared future.

They are a catalyst for bring communities together to explore the complexities of history and culture. Museums make an impact on a number of priority areas for government[7].

22. National Museums Northern Ireland also stated that for decades, museums had been seen as neutral venues and they had delivered many community relation programmes for schools and youth group across our sites[8].

Contributing to a positive international image of Northern Ireland.

23. Evidence was provided by contributors that demonstrated the important role that the museums sector plays in contributing to a positive image of Northern Ireland. NMNI pointed to how it had maximised opportunities provided by the uniqueness of its heritage product. NMNI also referred to the forthcoming ‘Cultural Olympiad’ which provided another opportunity for National Museums to help promote Northern Ireland’s reputation abroad[9].

24. DCAL also referred to the part museums play in helping Northern Ireland positioning itself on the world stage:

Museums are part of the process of helping position Northern Ireland as a forward-looking and progressive place to which people will want to visit and live and as a place for investment with a rich past and a positive future. One businessman is claimed to have said that his company came because of the incentives and stayed because of the people[10].

25. Health and well being

The benefits to mental health were referred to by the University of Ulster who stated that:

The opportunities for social engagement with friends and family provided by a visit to a museum must also be accounted for. The provision of museums and the arts makes for a happier and healthier society[11].

26. On the basis of the evidence presented, the Committee makes the following recommendation:

27. We recommend that the Executive acknowledges that the museum and heritage sector is an important industry in Northern Ireland with the potential to assist economic growth.

Chapter 2 - Work conducted so far to monitor the social and economic value of museums in Northern Ireland

28. There are a number of studies that have been undertaken by DCAL, the museum sector and academics in Northern Ireland to assess the value and impact of museums. The details of these studies, past and present are detailed below.

Economic Impact Study 2003

29. In 2003, an economic impact study was conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers and commissioned by the Heritage Lottery Fund with guidance from the Northern Ireland Museums Council. It sought to illustrate the contribution museums make to the economic life of Northern Ireland, but also to develop an understanding in the sector of the importance of demonstrating this contribution.

30. In terms of the economic impact of the sector, the research found that[12]:

- The 38 Accredited museums attracted 800,000 visitors in 2001, of whom 152,000 were from outside the region.

- Total income amounted to around £17.3 million in 2000/01, equating to around 0.1% GDP.

- The total expenditure of the sector is around £16.2 million, of which 85% is spent in Northern Ireland.

- The sector employed 650 people in Northern Ireland in 2003.

31. In terms of assessing the full economic impact of museums consistently in the future, it was concluded that data would have to be collected on such factors as:

- Direct and indirect employment.

- Details of any franchised operations that are dependent on a museum.

- Expenditure within the local economy.

- Visitor numbers.

- Visitor spend.

32. It also found that in addition to the 38 Accredited museums, a further 400 organisations existed at the time which could be considered museums[13], but that would be impossible to accurately estimate the full impact of the total museum sector without further in-depth, primary research’[14].

ValCAL Study 2008

33. The next major piece of research was carried out in 2008. The report was entitled “Research into the Social and Economic Value of Culture, Arts and Leisure in Northern Ireland" (known as ValCAL). The ValCAL report was commissioned by DCAL and carried out by PricewaterhouseCoopers, in collaboration with the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency.[15] It highlighted a number of potential social benefits, including those associated with tourism, education, health, regeneration, and social inclusion.[16]

34. However, the study did not proceed beyond Phase 1 because it became apparent that there was a lack of sufficient data to carry out a meaningful assessment of the economic and social benefits of investment[17].

35. The report concluded that the research infrastructure was dated and the sector would benefit greatly from guidance from DCAL regarding a more frequent evaluation framework.[18]

36. This would appear to contrast with the situation elsewhere. The Committee was informed that since at least 2005, museums bodies in England and Scotland have sought to establish a consistent methodology by which to measure and demonstrate both the economic and the social value of museums[19].

37. When questioned, in evidence, about whether there was any plans to update the ValCAL report, DCAL officials stated that a new economic and social research programme was been taken forward. Officials stated that this was a new step for the Department as it previously did not have a specific programme. Starting in April 2011, and among other things, it will look at how economic impact is measured, and what these impacts are.

DCAL’s role in assessing the economic and social impact of museums

38. In oral evidence to the Committee, officials explained that the Department’s role is to gather evidence on some of the social and economic impacts. This work includes the gathering and analysis of statistical evidence on visitor numbers to museums and collecting research evidence from DCAL’s own sources and others on the impact of museums.

39. In terms of ongoing research, DCAL commissions a series of modules in the continuous household survey and the young persons behaviour and attitudes survey on museums in Northern Ireland.

40. DCAL has also carried out a review, published in September 2010 of surveys from government departments and public bodies. A number of gaps were found in relation to museums which the Department is addressing through its research programme[20].

41. At a policy level, DCAL intends to incorporate the value and impact of museums into the museums policy. Specifically in the section on developing audiences, there will be more exploration of the economic value of museums to tourism[21].

42. A research paper commissioned by the Committee, suggests that a more systematic continuous evaluation of the impact of the museum sector should be carried out ‘so that a clear understanding is provided, in order for the appropriate strategies and funding to be developed[22].

43. In response to the research paper, DCAL informed the Committee that a target has been incorporated into the museums policy to ‘gather up-to date intelligence on the sector in support of policy implementation and strategy development’. However DCAL also made the point that the pressure of collating data from what are often small organisations with limited budget would need to taken into account[23].

Research by Northern Ireland Museums Council (NIMC)

44. In written evidence, the Northern Ireland Museums Council informed the Committee of the range of research that it undertakes to ensure that its activities are underpinned by sound intelligence, and that government policy and the plans of the museums’ governing bodies are well-informed.

45. Recent NIMC studies which have a bearing upon the economic and social impact of museums include:

- Volunteering in Local Museums in Northern Ireland (2010).

- Staffing and Employment Trends within Northern Ireland’s Museums (2010).

- Marketing Northern Ireland’s Museums (2009).

- Learning within Museums in Northern Ireland (2008).

- An Initial Review of the Economic Impact of Museums in Northern Ireland (2003) and updated in 2006 but not published[24].

46. The Council also directed the Committee to its survey of the museum sector in Northern Ireland - Mapping Trends in Northern Ireland’s Museums – undertaken in 2002 and 2007[25].

47. In terms of the future, The Northern Ireland Museums Council informed the Committee that it is committed to continuing its research activities in support of the sector within its 2011-15 Corporate Plan, and more particularly will focus upon further research into the economic and social impacts of museums during 2011-12[26].

Research by National Museums Northern Ireland (NMNI)

48. NMNI informed the Committee that it measures the value and impact of its work in a number of ways, which are designed to demonstrate value, improve quality and ensure the delivery of benefits from investment in capital and revenue programmes. However it stated that:

the extent of our work in this area has been governed by the level of staff and financial resources available[27].

49. NMNI operate an exit survey which is able to demonstrate the value and impact of Museums in various fields. This informs a series of Key Performance Indicators, some of which help to demonstrate the social and economic value of the organisation.

50. In written evidence, NMNI also referred to the ‘Inspiring Learning for All’ framework which is widely used in museums, libraries and archives in the United Kingdom. NMNI has suggested that the DCAL quality indicators could be further adapted to reflect the Inspiring Learning for All Framework, and the self-directed learning that takes place in museums[28].

51. NMNI is currently developing a new volunteer policy and procedures that will promote social inclusion and open up opportunities for learning and enhance employability. National Museums, informed the Committee, that the economic value of volunteering in the museum sector in Northern Ireland is yet to be fully developed. Research indicates that independent museums in the UK ‘benefit from the involvement of over 100,000 volunteers, contributing to the equivalent of £108m a year in value[29].’

Research by the University of Ulster

52. University of Ulster currently offers two Masters programmes in museum studies both of which aim to explore and foster best practice in the sector. They stated that there was potential to expand this learning provision to provide credited short courses and training programmes to foster good practice in the areas of social and economic value.

53. The Committee was informed of the independent research undertaken by research students and academics at the University of Ulster which has contributed to the understanding of the value and impact of museums in the region[30].

54. On the basis of the evidence presented, the Committee makes the following recommendations:

55. We recommend that the research infrastructure is urgently updated and that DCAL issues guidance regarding a more frequent evaluation framework.

56. We recommend that all the museums, libraries and archives in Northern Ireland must establish a consistent methodology by which to measure and demonstrate the economic and social value of Museums, including commonly-agreed standards for data collection. This should include data that measures indirect benefits to the local economy including indirect employment, goods and services and associated goods.

57. We recommend that any intelligence gathering (such as the types of information to be gathered and the methodology), should emerge as part of the key actions flowing from the museums policy.

58. We recommend that DCAL provides sufficient resources, in terms of expertise, staff and financial resources to support the museum sector’s ability to collect, on a consistent basis, robust data across the local museum sector.

59. We recommend that the ‘Inspiring Learning for All’ framework, which is widely used in museums, libraries and archives in the United Kingdom is further adapted and applied to the museum sector in Northern Ireland.

60. We recommend that research is conducted into the economic value of volunteering in the museums sector in Northern Ireland and is carried out jointly by NMNI and NIMC, which supports the development of a volunteering policy.

Chapter 3 - Understanding Economic and

Social Impacts

61. Throughout the course of the review, the Committee learnt of the numerous studies and progress, which had been made towards understanding how the impact of museums can be measured economically and socially.

62. The Committee was informed about how these various studies employed a range of different techniques and place different emphasis on various aspects of museum activity. National Museums Northern Ireland drew particular attention to work recently undertaken by the Association of Independent Museums in the UK and a report by the Heritage Lottery Fund which includes Northern Ireland analysis[31].

Economic value and impacts

63. The Museums, Libraries and Archives Council of England (MLA) conducted an extensive consultation exercise in 2008, resulting in a report which evaluates the various methodologies available and assesses the preferences of both the sector and stakeholders[32]. The report concluded that of the various economic appraisal techniques available, the following have the most relevance for museums:

|

Method

|

Description

|

Assessment

|

|---|---|---|

| Cost-benefit analysis | Identifies and analyses impacts in monetary terms and establishes whether benefits outweigh costs. | More often used as a decision-making tool than to demonstrate impacts after the event. |

| Multiplier analysis | Demonstrates the Gross Value Added (GVA) impacts on the local and wider economy. | Effective at illustrating ‘trickle down’ effects, but fails to capture broad range of social, cultural and educational benefits. |

| Contingent valuation | Asks users to place a value on the service offered. | Indicates value of a service, rather than just the economic impact. Difficulties in defining non-users, and in defining value ranges. |

| Social return on investment (SROI) | Combines multiplier analysis and contingent valuation to indicate both impact and value. | Offers flexibility in providing a range of indicators; can be used to monitor changes in impact of a museum through time. |

64. While there are advantages and disadvantages to each of these approaches, the National Museums Council informed the Committee that there was a general preference for the use of multiplier analysis methodologies across the museum sector[33].

65. In 2010, the Association of Independent Museums created an economic value toolkit which sets out a method to estimate the economic impact museums may have on their local economy, via a multiplier analysis. In oral evidence, NMNI referred to the possibility of developing an economic toolkit using this methodology for the museum sector in NI[34].

66. Research commissioned to inform this view found that that the SROI model (see table above) has been favoured in England, and a number of case studies exist which demonstrate how it can be used. This combines multiplier analysis and contingent valuation to indicate both impact and value[35].

67. Generally there was widespread agreement that much progress had been made in relation to the methodologies for measuring the economic value and impact of museums that have relevance to the museum sector in Northern Ireland. However the MLA report asserted that an important distinction should be made between economic impact and economic value[36].

Consultation with the sector indicated that economic impact and value methodologies must consider more than the income, expenditure and employment impacts of the services and must take into account wider social and economic impacts[37].

68. DCAL also cautioned against expressing the value of museums in just economic terms. This, they stated, undervalued other important aspects of museums. In oral evidence, DCAL explained that its planned economic and social research programme will measure the wider economic benefit and will also explore a number of approaches to the value of participation. It will look at the continued valuation approaches (see table above) and the subjective well-being analysis or ‘happiness indicator’[38].

Social impact and values

69. It was evident that little research had been undertaken regarding the social benefits of museums on a consistent basis across the sector in Northern Ireland. A research paper states:

Little research has been undertaken regarding the social benefits of museums in Northern Ireland, despite the importance of the sector nationally and internationally, evidenced throughout. Unlike the sports and arts sectors, museums benefit from having a clear ‘customer base’, and the impact of the sector should be easier to facilitate. Although the literature base illustrates that wider studies tend to place more emphasis on the economic rather than the social benefits of the sector, an effective social evaluation tool could be developed and rolled out on a consistent basis across Northern Ireland’s museum sector[39].

70. Throughout the review, the Committee was made aware of the notable variety of measurement of approaches and challenges when measuring the social impacts of the museum sector. One researcher had identified twenty social impact measurement methods, while another study suggested upwards of thirty[40].

Difficulties in assessing the value and impact of museums in Northern Ireland

71. Despite the various studies referred to above, it is clear that there are a number of methodological issues associated with assessing the value and impact of museums in Northern Ireland.

Lack of robust data

72. The Committee was informed that the NIMC research programme had identified a lack of robust and consistent data collection across the local museum sector in Northern Ireland which was making it difficult to provide evidence of the impact of the sector as a whole[41]. This view was supported by DCAL.[42] In written evidence, the NIMC stated:

A common opinion of commentators on museums’ impact is the prerequisite need for specific, robust data, collected over time, applied to an appropriate methodology, with a pre-agreed objective in mind. The current capacity of the sector in Northern Ireland to do this is weak. As NIMC’s Marketing Northern Ireland’s Museums (2009) study highlighted, there is little by way of a common or standardised approach to the collection of even the basic data in our museums and this would need to be rectified in order that the ubiquitous impacts could be properly assessed.

Standardised approach

73. In written evidence, NMNI said it recognised the importance to government, stakeholders and funders of tracking social and economic impact, especially given the prevailing economic situation and the austerity measures to come. However it highlighted the fact that:

The sector currently lacks a universal model which can consistently demonstrate outcomes across museums. Whilst the introduction of such a model would be welcome, and potential examples exist, the cost of implementation would require careful consideration[43].

74. The benefits of a universal model were not wholly favoured by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the NIMC.

75. The NIMC, in written evidence, referred to the difficulties of a ‘one size fits all’ approach given the diversity of the museum sector. They said:

This diversity in their location, governance, funding base and the focus of their collections is a fundamental strength of the sector. It does however preclude any ‘one size fits all’ methodology for assessing impacts, and quite subtle approaches are required in order to achieve an understanding of impacts that stand somewhere between high-level assessments (that may not be particularly informative locally) and discrete, site specific assessments (from which comparative or collective conclusions are difficult to draw)[44].

76. Heritage Lottery qualified their comments by saying:

There has been progress on and more agreement around methodologies for the different types of benefits that museums deliver. For example...there is a need to get some sort of agreement on the methodologies used and the ways of measuring different social and economic benefits.

77. In oral evidence, the University of Ulster pointed to well established models outside of Northern Ireland to measure economic and social value of museums:

one could say there are gaps in Northern Ireland and that we need to sit down and do similar work. It would be a matter of bringing people together to undertake that work[45].

78. There was much interest in a UK wide group known as ALMA UK (Archive, Libraries and Museum Alliance), of which the Northern Ireland Museums Council is a member. It is consulting with key stakeholders as to the potential of adopting a standardised approach to data collection to assess impact across the sector, at both the devolved nation level and UK-wide. However, in terms of who should take the lead, it was not clear who that should be if an exercise of this nature was undertaken.

Measuring Cultural Impacts

79. The need to measure cultural benefits was referred to during the course of the Review. In written evidence NMNI stated:

“If we do develop a model, rather than simply looking at the economic and social benefits, we might also include, the cultural benefits of museum activities[46].

80. NIMC supported this view stating

The primacy of measuring the economic and social impacts, perhaps since the mid-1990’s, has gone hand in hand with the culture of accountability through targets and qualitative performance measurement. The intrinsic value of culture, particularly as represented by museums, has been seen to lack currency against this background. It is to the sector’s credit that it has sought to and succeeded in making a difference in social and economic terms. This has been enabled by the flexibility of programming, the commitment of staff and the underlying spirit of what museums are about. Notably that has not seen an appropriate quid pro quo, through which cultural impacts are sought from those publicly funded bodies concerned directly with social and economic development. A clear and more comprehensive picture of museums’ contribution may be had through an assessment of their cultural, social and economic impact[47].

81. Museums Galleries Scotland however pointed to the difficulties in measuring cultural impact and said:

It is not always easy to define and measure the question of value in relation to culture. Certain aspects of social and economic impact can be more easily measured than other. For example, it can be difficult to measure long term impact, especially where a range of initiatives may be contributing to social changes[48].

82. On the basis of the evidence presented, the Committee makes the following recommendations:

83. We recommend that DCAL consider the development of an economic toolkit, using a similar methodology as that used by the Association of Independent Museums, as part of its planned economic and social research programme.

84. We recommend that the lack of research regarding the social benefits of museums on a consistent basis is addressed in DCAL’s economic and social research programme, and that a social evaluation tool is developed in consultation with the museums sector.

85. We recommend that the Department, local authorities and the museum sector use independent research on the impact and value of museums carried out by academics and experts to avoid duplication and additional costs.

86. We recommend that more research is carried out into the cultural value and impact of museums resulting in an effective evaluation tool being developed which can ultimately incorporate the economic, social and cultural impacts of the museum sector.

Chapter 4 - Assessing how information about the social and economic impact of Museums could be used to assess value for money across government.

87. As the previous chapters indicated, there are numerous studies that demonstrate the wider economic and social benefits of museums and support the argument that the museum sector provides value for money across a number of areas including cultural tourism, the economy, education and life-learning and health. It was evident to the Committee that there was a substantial amount of data that could be applied to demonstrate value for money across government.

88. Given that many of the benefits extend beyond the remit of culture, arts and leisure, the Committee agreed that information about the social and economic impact of museums could be used to assess value for money across government.

89. As the University of Ulster stated:

Far too often we miss a trick when it comes to the potential of culture and arts for generating economic revenue, rather than just something that people engage as a pastime and on which they spend a little bit of their pocket money. There is a far greater potential there that is not being fully exploited.[49]

90. The intention to assess value for money was welcomed by a number of contributors to the review. For example,

The Northern Ireland Museums Council welcomes and supports the Committee’s intention to review of the value and impact of museums in Northern Ireland. By their very nature museums operate in the public interest and do so, in the main, with support from the public purse. It is essential therefore that the full range of impacts and their contribution to Northern Ireland’s economy and society is more fully recognised. NIMC is of the view that the Committee’s inquiry has the potential to fully reveal the extent of the sector’s wide-ranging contributions, to show that the sector represents extremely good value for money, and is worthy of significant further investment[50].

91. Furthermore research carried out by the NIMC was referred to as an example of research that had demonstrated how the NIMC had achieved the aims of the Programme for Government and value for money.[51]

92. In terms of making the case that the museums provide value for money, the HLF informed the Committee that it had invested nearly £30million in museums in Northern Ireland[52]. In demonstrating economic impact and value for money, HLF state that the tourism aspect of economic impact is only one argument for public investment in museums and in culture. There is also the supply chain of sector related activites to the museums sector including the supply of the raw material for the creative cultural industries.

93. In written evidence, NMNI supported this point with reference to how cultural infrastructure has had a direct impact on the local construction industry. The £28.8 million, invested by NMNI on flagship projects has supported construction industry jobs, benefitted local suppliers and encouraged the procurement of locally sourced goods. They stated, by

Using a social impact model it is possible to establish the economic benefit to the construction industry in terms of direct jobs, indirect and induced jobs. The same applies to the procurement of goods and service so that the overall effects of this investment are hugely significant for Northern Ireland. There is also benefit to the economy through PAYE and Corporation Tax returns of local people and companies.

94. HLF also stated that, for every £1 million it spends in a region’s tourism, revenues worth

£4 million are generated. In support of this, NMNI stated that HLF’s grant of £4.7m to the Ulster Museum would be worth £19.7m to the local economy over 10 years[53].

95. The University of Ulster referred to research by Natural History Museum which mirrored these findings. The research found that for every £1 of government grant to museums, the benefit to the local economy is quadrupled.[54]

96. In terms of investment, NIMC stressed that while evidence suggests that economic and social benefits do invariably accrue from what museums do, the economic and social benefits are directly proportionate to the levels of investment in the primary functions of museums; i.e.

the ability to collect, preserve, display and interpret their collections for the edification, inspiration and enjoyment of the public[55].

97. From the evidence gathered during the course of the review, it was evident to the Committee that there is a substantial amount of data that could be applied to demonstrate value for money across government. However this is not withstanding the difficulties referred to in Chapter 4 on assessing the economic and social value of museums.

Acknowledging the value and impact of museums

98. It became clear to the Committee, that while there are numerous studies demonstrating the economic and social value of museums, there is a lack of understanding and acknowledgement about the economic value of museums by the general public in Northern Ireland. With reference to the museum sector, the University of Ulster stated that some sectors are aware of the importance of museums but that there is a need for joined up thinking or collaboration, as this is how value for money is best achieved[56].

Social impact versus economic impact

99. In terms of assessing economic and social impact and value for money, tensions can arise. In written evidence, the NIMC drew the Committee’s attention to the direct conflicts between economic and social impacts. By way of example, they stated, the issue of admission charge versus the access dilemma faced by some museums, particularly those in the voluntary sector who rely upon ticket income to sustain their operations. Reference was made to the debate around the abolition of entry charges at the national museums in England, Scotland and Wales where free entry saw increased visitor service costs which were not wholly covered by compensation from government for lost income.

100. The NIMC also referred to other obvious tensions including,

the role museums often undertake as custodians of a building of significant heritage value versus physical access requirements and ‘value for money’ cost of running the institution, or balancing access to the collections with the a priori preservation responsibility.

101. According to NIMC, another notable issue was that associated with definitions and how this can pose problems between policy makers and the museum sector. There was a need for[57]:

clarity in definitions, approach and the mutual understanding amongst those with particular interest in the impacts of museums. The goals of ‘community cohesion’ and ‘social inclusion’ for instance, while variously defined, continue to be perceived as somewhat nebulous and a recent study points to a gap in understanding between the policymakers responsible for developing the rationale for government investment and the sector professionals who develop and deliver the programmes that generate social impact.[58]

102. Public Service Agreements and measuring the value of Museums

In written evidence, DCAL informed the Committee that it uses Public Service Agreements (PSAs) to demonstrate the value of museums, at a high level, across government in Northern Ireland. PSAs also measure the performance of National Museums and set the organisation strategic goals[59].

103. Proposed PSA in relation to rebalancing the economy

DCAL informed the Committee that the current PSA relating to visitor numbers in part demonstrates the economic value of National Museums. However, under consideration is whether a more focused PSA showing the value of National Museums to Northern Ireland’s cultural tourist product could be developed. The proposed PSA target would be in addition to a more general attendance target and would measure the number of out of state visitors to museums.

104. Proposed PSA in relation to the social value of museums to formal education

The current target relating to providing educational visits demonstrates the social value of museums in supporting the formal education sector. However, according to DCAL, the proposed PSA would focus attention on the benefits to education of enriching learning through engagement with collections in museums[60].

105. DCAL stated:

This would reinforce the goal in the draft Museums Policy that every child in Northern Ireland has the opportunity to a visit a museum as part of a curriculum based activity.

106. During the course of the review, references were made to the contribution that the museum sector makes to the STEM (Science, Technology Engineering and Maths) subjects. For example, NMNI referred to its learning programmes that support the STEM agenda[61]. However in oral evidence, NMNI explained that they have not reached the stage of measuring that yet, but are developing a programme[62].

107. Maximising Resources through Strategic Partnerships

NMNI stated it was aware of the importance of delivering strategic partnerships and this was reflected in the recent development of a Directorate of Learning and Partnership. NMNI stated that there was increasing recognition within government policy of the necessity to share resources and develop partnerships with mutually advantageous objectives. Within DCAL, the Learning Strategy has, as one of its central tenets, the aim of developing partnerships within the DCAL family and further afield[63].

108. NMNI informed the Committee that it had a philosophy of working in partnership with a range of sectors and industries including tourism, education, the creative industries, business, community and voluntary organisations to name but a few. Some of its current partners included the Workers Education Association, Queen’s Festival, Age NI and the Polish Community, reflecting a complete spectrum of objectives[64].

109. The need for greater collaboration within the museum sector was stressed by the University of Ulster and Heritage Lottery Fund, which it was argued, would help demonstrate the value for money case. HLF called for a greater degree of cooperation in any research programmes between local and national museums. NMNI agreed that there needed to be coherence across the sector and greater partnership working between NMNI and NIMC[65].

Linkages with other Departments

110. In terms of linkages with other Government Departments, it would appear that there are linkages which exist with DETI in relation to measuring the contribution that cultural tourism makes to the economy. For example:

Tourism Strategy for Northern Ireland to 2020 has significant references to the important role cultural tourism contributes to the overall tourism strategy and how DCAL can contribute to this[66].

111. The Draft Government STEM Strategy (August 2010) also acknowledges that museums, ‘support and enhance the delivery of the curriculum and provide STEM experiences and insights that inspire and add value and sees museums as having a key role in implementing the strategy’.[67]

112. However, it is not clear if linkages exist with other government departments in relation to the wider economic and social impact and value of the museum sector to the economy.

113. A point which emerged in discussion during the University of Ulster submission was that examining and demonstrating the economic and social value of museums could usefully be an Executive-wide commitment, with evidence considered, and programmes designed, by a number of different departments and bodies[68]. A similar point was made during the oral evidence session with DCAL officials[69].

114. On the basis of the evidence presented, the Committee makes the following recommendations:

115. We recommend that DCAL’s new PSAs include targets to measure the contribution of the STEM subjects to the museum sector.

116. We recommend a greater degree of co-operation between NIMC and NMNI on research programmes.

117. In light of budgetary constraints of the 2011-2015 period, we recommend that the Executive commit to examining, across departments the economic and social value of museums with evidence considered, and programmes designed, that fully maximise the social and economic contribution of the museum sector to the economy.

Chapter 5 - Areas of good practice within the museums sector outside of Northern Ireland

118. There is a significant body of research on the economic and social impact of museums. As was clear from the evidence, over the last decade, a large amount of work has taken place to form and test appropriate, flexible and effective methodologies to indicate the impact and value of museums. The following is a brief review of the work undertaken in recent years by each of the regions of the UK, and Ireland.

119. England

In England, the lead museums body is currently the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (MLA).

120. In a written submission, the Committee was informed of the MLA’s research programme. MLA has been a contributor to a joint research programme led by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, also involving Arts Council England, English Heritage and Sport England, with the aim of strengthening understanding of how best to deliver high quality cultural (and sporting) opportunities to widest audience[70].

121. In 2010, this jointed research programme produced a report which drew together analyses of the factors which drive engagement in culture and sport. It also produced an extensive database of over 5,000 studies on culture and sport engagement. MLA claims that this database is the single most comprehensive database of its kind in the world[71].

122. MLA has also produced a report that builds on the work published by CASE. Measuring the value of culture: The report to DCMS, assesses the different approaches to generating the value associated with engagement in culture and sport. This analyses both a range of economic valuation approaches, and also a set of emerging ‘well-being-based’ techniques. The report makes a number of recommendations, including action by DCMS to create clear guidance on how to use economic valuation (rather than economic impact) techniques of the kind already used across central government, and that the department should develop closer links with academics working in the area of cultural economics so that good practice continues to be followed.

123. In terms of museum-specific studies, MLA has produced a number of studies in recent years examining the relationship between museums and health benefits, cultural diversity, and volunteering[72].

124. The Committee was informed that since 2005, there has been a concerted effort to develop sound methodologies and an evidence base so that the value and impact of museums can be measured, compared and demonstrated[73].

125. In 2008, MLA produced some detailed guidance on the range of approaches available to measure economic impact. This concluded that though multiplier analysis and cost benefit analysis have their uses, a Social Return on Investment (SROI) model, combining an expression of user preferences with multiplier analysis, is the most beneficial. This technique is more challenging but a number of museums in England have now used the SROI methodology to indicate their social and economic value[74].

126. Various categories of social impact have been defined, and case studies exist to illustrate the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. A case study from Tyne and Wear Museums illustrates the importance of defining the desired social impact, and the methodology to be used in assessing the outcome, at an early stage in any new project or programme[75].

127. It would appear that no similar work has been carried out within the museum sector in Northern Ireland on the SROI methodology.

128. Other forms of value and impact were also summarised briefly for the Committee, including cultural heritage tourism, educational and cultural factors. While it was established that a methodology for educational impact is now well-established, measuring cultural impact is in its infancy and will require further development before empirical measures can be applied in practice[76].

129. Aside from work conducted by the MLA, the Association of Independent Museums produced an economic impact paper in 2010, including an economic value ‘toolkit’ which sets out a straightforward method by which museums can estimate the impact they may have on their local economy.[77] The toolkit sets out the calculations to be used to quantify (i) tourism impacts (ii) employment impacts and (iii) the impacts of spend on goods and services. In just six pages, the relevant definitions, formulae and necessary economic assumptions are laid out in a way which is designed to allow independent museums to ‘accurately and quickly generate the data that is needed to estimate economic impacts’.[78]

130. In written evidence NIMC referred to this economic toolkit as a possible model to measure economic value within the Northern Ireland.

Wales

131. The lead museums body in Wales; CyMAL is a division of the Welsh Assembly Government (WAG). In written evidence, the Committee was informed of the CyMAL’s museums’ strategy which was produced in June 2010 - “A Museums Strategy for Wales 2010 – 2015".

132. The strategy identifies three themes which relate specifically to the issue of social and economic impact and value:

- Museums for everyone: Museums will contribute to living communities, promote the values of a fair and just society and provide lifelong learning opportunities for all.

- A collection for a nation: Museums will hold, care for and continue to develop collections for the nations which represent our rich and diverse culture.

- Working effectively: Museums will manage their sites, operations, collections and people effectively to provide services for citizens that are relevant, robust and sustainable.

133. In 2007 CyMAL published Spotlight on Museums which gathered information from the 160 organisations in Wales that hold collections and display them to the public. 106 organisations responded providing economic data such as budgets, staff levels and volunteer input. The Committee was informed that is exercise will be repeated in 2011 and 2015 providing comparisons and trends across the timeframe[79].

134. The framework underpinned organisational development that led to service improvement. It also served to measure outcomes and document the impact of a museums work. A research paper highlighted that the benefit of this framework, rolled out across the sector, was that all museums, libraries and archives operated a uniform approach which provided an opportunity to quantify the social value of museums[80].

Scotland

135. The majority of work on this issue carried out in Scotland has been conducted by Museums Galleries Scotland (MGS). According to MGS:

25 million people visit each year, and that £800 million is contributed to the Scottish economy[81].

136. MGS has carried out a number of relevant studies in recent years, including the impact of museums and galleries to Scottish tourism, and the impacts on their local communities[82].

ALMA-UK (Archives, Libraries and Museums UK)

137. MGS is the lead partner in ALMA-UK (Archives, Libraries and Museums UK), which is currently conducting an ‘Economic Impact’ project as a result of a ‘realisation that there is a proliferation of studies in this area, with a variety of methodologies and that there was the need to step back and take stock of the methods and their applicability’[83].

138. The Committee was informed that the purpose of this project is firstly to analyse economic impact methodologies for archives, libraries and museums and support organisations from the sector, and secondly to create a series of potential toolkits that could be used by the sector.

139. As part of the research, ALMA UK is seeking to consult with key stakeholders as to the potential of adopting a standardised approach to data collection, at both the devolved and national level and UK-wide[84].

140. A report will derive from the first phase, and this is expected to be published in February 2011. The pilot studies which will make up phase two of the project will take place in various parts of the UK, and will include Northern Ireland[85].

Republic of Ireland

141. The Heritage Council is the lead museums body in the Republic of Ireland. No museums-specific study has been carried out recently, though there are a number of related studies which have examined the economic contribution of the arts, and of local authority heritage provision.

142. In 2007, a study was published which examined the value of heritage in Ireland, including both natural and built heritage, but also museums[86]. The study involved a survey of 1008 adults from 100 randomly selected points throughout the Republic of Ireland. Some key conclusions which stand out from the research are that over 90% of people think it is very or fairly important to protect heritage, and there is a strong desire for penalties for those who damage heritage. A contingent valuation technique was used, which indicated a value for heritage protection across the whole Irish population of €89.54 million[87].

143. In 2010, an economic evaluation of the County Heritage Plan (CHP) was published. CHP is managed by the Heritage Council, and provides a framework through which funding and support for heritage protection is promoted at the county level. The report concluded that CHP supported 1,085 jobs, which when a multiplier effect is applied is estimated to be 1,315 full-time equivalent jobs. The net wage injection into the economy is estimated at €30.1 million, and the contribution to the Exchequer is estimated at €5.3 million. The expenditure of €30.1 million in net wages resulted in an estimated total income effect of €45.1 million in the economy over the period from 2004 to 2008. In terms of spending on secondary services, including advertising, printing, graphic design, hotel facilities and catering services, €565,377 was spent between 2004 and 2008, which with a multiplier effect suggests a total expenditure impact of €848,065[88].

144. In terms of the contribution made by heritage to cultural tourism, Tourism Ireland indicate that in 2009, around 3,045,000 overseas visitors to Ireland engaged in historical/ cultural visits, and 46% of total overseas visitors carried out historical/ cultural visits while in the country. Overseas visitors to Ireland generated revenues of €3.1 billion[89].

145. The Heritage Council stated that it had an ongoing and positive relationship with the Northern Ireland Museums Council and in particular has partnered NIMC in the running of the All Island Museum of the Year Awards. However it would not appear that this extends to joint collaboration on any type of economic and social impact of the museum sector on an all-island basis.

146. On the basis of the evidence presented, the Committee makes the following recommendations:

147. We recommend that the Department identify examples of good practice in measuring the economic and social impact of museums, and applies this to improving the assessment of the social and economic value and impact of museums in Northern Ireland.

148. We recommend that the Museum Sector in Northern Ireland continues to be represented by the Museums Council on the ALMA project and that the specific research needs of the museum sector, and any pilot projects which may be undertaken, are given adequate support through the course of the project.

[1] Appendix 3

[2] Northern Ireland Museums Council. 2010. Staffing and Employment Trends within Northern Ireland’s Museums:

[3] Appendix 3

[4] HLF, Investing in Success, March 2010

[5] Appendix 3

[6] Appendix 2

[7] Appendix 3

[8] Appendix 3

[9] Appendix 3

[10] Appendix 2

[11] Appendix 3

[12] Appendix 4

[13] Appendix 4

[14] Assembly Research Paper, Appendix 4.

[15] Appendix 4

[16] Appendix 4

[17] Report on the Committee’s Inquiry into the Funding of the Arts in Northern Ireland, November 2009

[18] Appendix 4

[19] Appendix 4

[20] Appendix 3

[21] Appendix 2

[22] Appendix 4

[23] Appendix 3

[24] Appendix 3

[25] Appendix 3

[26] Appendix 3

[27] Appendix 3

[28] Ibid

[29] Appendix 3

[30] Appendix 3

[31] Appendix 3

[32] Appendix 4

[33] Appendix 3

[34] Appendix 2

[35] Appendix 4

[36] Jura consultants. 2008. Economic Impact Methodologies for the Museums, Libraries and Archives Sector: What works and what doesn’t. Museums, Libraries and Archives: pp41.

[37] Appendix 3

[38] Appendix 2

[39] Appendix 4

[40] Appendix 3

[41] Appendix 3

[42] Appendix 3

[43] Appendix 3

[44] Appendix 3

[45] Appendix 2

[46] Appendix 3

[47] Appendix 3

[48] Appendix 3

[49] Appendix 2

[50] Appendix 3

[51] Appendix 2

[52] Appendix 2

[53] Appendix 2

[54] Appendix 2

[55] Appendix 3

[56] Appendix 3

[57] Appendix 3

[58] Appendix 3

[59] Appendix 3

[60] Appendix 3

[61] Appendix 2

[62] Appendix 2

[63] Appendix 3

[64] Appendix 3

[65] Appendix 2

[66] Appendix 3

[67] Appendix 3

[68] Appendix 2

[69] Appendix 2

[70] Appendix 3

[71] Appendix 3

[72] Appendix 4

[73] Appendix 4

[74] Appendix 4

[75] Appendix 4

[76] Appendix 4

[77] Appendix 4

[78] Appendix 4

[79] Appendix 3

[80] Appendix 4

[81] Appendix 3

[82] Appendix 4

[83] Appendix 3

[84] Appendix 3

[85] Appendix 4

[86] Appendix 3

[87] Appendix 4

[88] Ibid

[89] Ibid

Chapter 4 - Assessing how information about the social and economic impact

of Museums could be used to assess value for money across government.

Chapter 4 - Assessing how information about the social and economic impact

of Museums could be used to assess value for money across government.

Appendix 1

Minutes of Proceedings

Thursday 25 November 2010

Antrim Library, Antrim

Present: Mr Barry McElduff MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Declan O’Loan MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Mr Thomas Burns MLA

Mr William Humphrey MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

Mr Ken Robinson MLA

Apologies: Lord Browne MLA

Mr Billy Leonard MLA

Mr Kieran McCarthy MLA

In attendance: Ms Lucia Wilson (Clerk)

Miss Emma Patton (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Jonathan Lamont (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Chris Baird (Clerical Officer)

Ms Alice McKelvey (Assistant Legal Advisor)

10.47a.m The meeting opened in closed session.

8. New Committee inquiry – options for the way forward

Agreed: The Committee agreed to undertake an inquiry on the economic and cultural potential of the museum sector in NI.

Mr Barry McElduff

Chairperson, Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure

2 December 2010

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 2 December 2010

Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Barry McElduff MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Declan O’Loan MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Lord Browne MLA

Mr Thomas Burns MLA

Mr William Humphrey MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Mr Billy Leonard MLA

Mr Kieran McCarthy MLA

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

Mr Ken Robinson MLA

Apologies: None

In attendance: Mrs Cathie White (Clerk)

Miss Emma Patton (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Jonathan Lamont (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Chris Baird (Clerical Officer)

10.04 a.m The meeting opened.

7 New Committee Inquiry

The Committee discussed the timeline for the Committee’s new inquiry into museums.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to defer a decision on the Terms of Reference until next week’s meeting.

Agreed: The Committee agreed that they would carry out a focused compact review on the value and impact of Museums and that there was no need to issue a public notice.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to request Research and Library Service to provide a suggested list of consultees.

Mr Barry McElduff

Chairperson, Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure

09 December 2010

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 9 December 2010

Room 21, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Barry McElduff MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Declan O’Loan MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Lord Browne MLA

Mr Thomas Burns MLA

Mr Billy Leonard MLA

Mr Kieran McCarthy MLA

Mr Raymond McCartney MLA

Mr Ken Robinson MLA

Apologies: Mr David Hilditch MLA

Mr William Humphrey MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

In attendance: Ms Lucia Wilson (Clerk)

Ms Sian Woodward (Bill Clerk)

Miss Emma Patton (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Jonathan Lamont (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Chris Baird (Clerical Officer)

Dr Dan Hull (Research Officer)

10.34 a.m The meeting opened.

8. New Committee review into museums

Dr Dan Hull briefed the Committee on the impact and value of museums.

Agreed: The Committee agreed to the Terms of Reference for the review.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the title of the review as, ‘Review into the Value and Impact of Museums in Northern Ireland’.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the list of consultees for the Review.

Agreed: The Committee agreed the draft press release for the Review.

Mr Barry McElduff

Chairperson, Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure

09 December 2010

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 3 February 2011

Room 21, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Barry McElduff MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Declan O’Loan MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Lord Browne MLA

Mr Thomas Burns MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Mr William Humphrey MLA

Mr Kieran McCarthy MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

Mr Ken Robinson MLA

Mr Pat Sheehan MLA

Apologies: Mr Billy Leonard MLA

In attendance: Ms Lucia Wilson (Clerk)

Miss Emma Patton (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Jonathan Lamont (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Chris Baird (Clerical Officer)

10.21am The meeting opened.

9. Committee Review into the value and impact of museums – Oral evidence session – University of Ulster – Museums and Heritage Studies

The Committee considered the briefing paper from the University of Ulster.

11.50 a.m The following representatives joined the meeting.

11.50 a.m Mr McCarthy joined the meeting.

Dr Elizabeth Crooke - Senior Lecturer, Museum and Heritage Studies

Prof. Pól Ó Dochartaigh – Dean of the Faculty of Arts

The representatives provided evidence to the Committee Review into the Value and Impact of Museums.

A question and answer session followed.

12.12 p.m Mr McClarty left the meeting.

12.13 p.m Mr Humphrey left the meeting.

12.16 p.m Mr Burns left the meeting.

12.24 p.m Mr Burns rejoined the meeting

12.24 p.m The representatives left the meeting.

10. Committee Review into the value and impact of museums – Oral evidence session – Northern Ireland Museums Council

The Committee considered the briefing paper from the Northern Ireland Museum Council.

12.24 p.m The following representative joined the meeting.

Chris Bailey, Director

The representative provided evidence to the Committee Review into the value and impact of museums.

A question and answer session followed.

12.31 p.m Mr Hilditch left the meeting.

12.45 p.m The representative left the meeting.

Mr Barry McElduff, MLA

Chairperson, Committee for Culture, Arts and Leisure

10 February 2011

[EXTRACT]

Thursday 10 February 2011

Room 21, Parliament Buildings

Present: Mr Barry McElduff MLA (Chairperson)

Mr Declan O’Loan MLA (Deputy Chairperson)

Lord Browne MLA

Mr Thomas Burns MLA

Mr David Hilditch MLA

Mr William Humphrey MLA

Mr Kieran McCarthy MLA

Mr David McClarty MLA

Mr Ken Robinson MLA

Mr Pat Sheehan MLA

Apologies: Mr Billy Leonard MLA

In attendance: Ms Lucia Wilson (Clerk)

Ms Sian Woodward (Bill Clerk)

Miss Emma Patton (Assistant Clerk)

Mr Jonathan Lamont (Clerical Supervisor)

Mr Chris Baird (Clerical Officer)

10.35am The meeting opened in closed session.

10.50am The meeting moved into opened session.

6. Assembly Research paper – Assessing the Impact and Value of Museums

The Committee considered the Assembly Research paper.

Dr Dan Hull briefed the Committee on the Impact and Value of Museums.

11.24am Mr Burns joined the meeting.

11.35am Mr Burns left the meeting.

A question and answer session followed.

7. Committee Review into the value and impact of museums – Oral evidence session – Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

The Committee considered the briefing paper from the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure.

11.37am The following officials joined the meeting.

Alastair Hughes, Head of Museums and Libraries Branch – DCAL

David Polley, DCAL Official

Patrick Neeson, Principal Economist – DCAL

The officials provided evidence to the Committee Review into the value and impact of museums.

A question and answer session followed.

11.52am Mr Burns rejoined the meeting.

12.05pm The officials left the meeting.

12.05pm Lord Browne left the meeting.

Committee Review into the value and impact of museums – Oral evidence session – Heritage Lottery Fund

The Committee considered the briefing paper from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

12.05pm The following representatives joined the meeting.

Paul Mullan, Head of Heritage Lottery Fund Northern Ireland

Gareth Meer, Research Manager – Heritage Lottery Fund

The representatives provided evidence to the Committee Review into the Value and Impact of Museums.

A question and answer session followed.

12.23pm Mr Humphrey left the meeting.

12.26pm Mr Burns left the meeting.

12.26pm Mr McClarty left the meeting.

12.27pm Mr Humphrey rejoined the meeting.

12.34pm Mr Sheehan left the meeting.

12.36pm The Deputy Chairperson left the meeting.

12.37pm Mr Sheehan rejoined the meeting.

12.39pm The representatives left the meeting.

Committee Review into the Value and Impact of Museums – Oral evidence session – National Museums Northern Ireland

The Committee considered the briefing paper from the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure.

12.39pm The following representatives joined the meeting.

12.39pm The Deputy Chairperson rejoined the meeting.

Paddy Gilmore, Director of Learning & Partnership – NMNI

Dr Jim McGreevy, Director of Collections and Interpretations – NMNI

Gillian McLean, Director of Marketing Communications & Trading - NMNI

The representatives provided evidence to the Committee Review into the value and impact of museums.

12.48pm Mr Hilditch left the meeting.

A question and answer session followed.